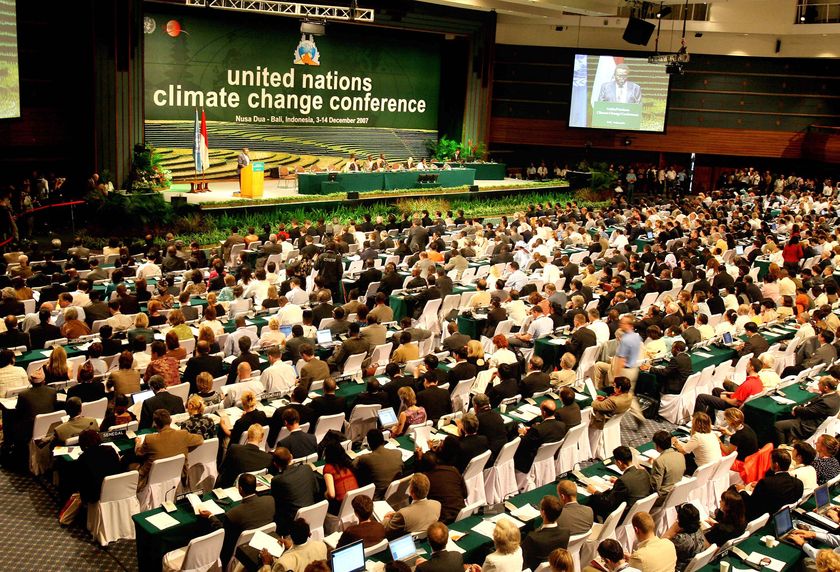

The UNFCCC-Kyoto approach, as most recently articulated in the 2007 Bali Conference can be summarized into three simple propositions: developed countries should adopt national emission reduction targets; developing countries should undertake mitigation actions; and developed countries should provide developing countries with mitigation financing.

Each of these is contested. On the first, my analysis of the emissions targets so far announced by developed countries (the EU, Canada, Australia and now, under its new President, the US) suggest an implied reduction target for developed countries as a group of between 10 and 20 per cent by 2020 over 1990 levels, short of the 25-40 per cent demanded by developing countries.

On the second, there are positive signals from most developing countries that they are prepared now to do more to mitigate climate change. But what they will commit to internationally, if anything is unclear. The language of actions signals that they will not sign up to binding targets. In the best case, they might sign on to one-sided emissions targets, which carry reward for being met or exceeded but no sanction for being violated. Alternatively, developing countries might commit to policy action plans. What these commitments, whatever their form, would add up to is also unclear. A best case might be that per capita emissions of developing countries stay at their 2012 levels. A worst case would be that their emissions continue to grow at business as usual rates.

An agreement for 2020 involving a 20 per cent reduction in emissions by developed countries over 1990 levels and a flattening of per capita emissions in developing countries post-2012 would not satisfy many environmentalists, but would be a real achievement, one which would reinvigorate the global climate change mitigation regime.

Whether such an agreement will be reached depends mainly on the third prong of the current negotiating framework: the provision of financing by developed to developing countries. This is perhaps the most problematic area of all. The Clean Development Mechanism – which provides carbon credits to developing countries for emission-reducing projects – is popular with developing countries, and it is unlikely that the CDM will be abolished. There are various worthwhile proposals for reform of the CDM, but its most important feature cannot be altered.

Any reduction in emissions the CDM delivers in a developing country stands in place of a reduction of emissions in a developed country. Therefore, if the CDM is the only mechanism generating emission reductions in developing countries, global emission reductions will be a function solely of developed country targets. And developed country targets alone are simply not ambitious enough to make a serious dint in global emissions. There need to be constraints on developing country emissions in addition to, not only in substitution of, reductions agreed to by developed countries.

International emissions trading is another financing option, but the uncertainties around trading and the time it will take to develop an international trading system make it inappropriate as a vehicle for kick-starting mitigation in developing countries.

This leaves public funding. Developing countries demand public funding; developed countries counter that funding of the required magnitude can only be mobilized by markets. Yet, if the political appetite for serious international public funding for mitigation is lacking in developed countries, the appetite for the sort of ambitious targets that would make sense of an international-offset approach to financing is completely absent. A mix of market and public funding is required. The Garnaut Review recommended that developed countries commit to an International Low-Emissions Technology Commitment of about $US100 billion a year, of which about half would be expensed in developing countries. This would require, for example, Australia committing to spend $A1.5 billion every year in developing countries to support mitigation. Affordable, not unthinkable, but a different order of magnitude to the tens of millions being committed through the aid program at this stage.

To summarize, while the world has a negotiating framework for climate change mitigation, it is a framework that is largely still to be filled in. Only in first area – developed country commitments to 2020 emission targets – do we have something approaching a clear idea of what a post-Kyoto agreement might look like. This is itself progress. Even if developing countries refuse to participate more fully in a post-Kyoto agreement, it is essential that developed countries move forward with a successor agreement if only to restore their credibility and to incentivize the technology development and deployment that will be vital to the success of global mitigation.

That said, securing fuller developing country participation is obviously of great importance. Developing countries need to reveal what they might be prepared to sign up to. And developed countries need to move quickly to fill both the credibility gap – to demonstrate that they are actually serious about reducing emissions – and the financing gap – by getting realistic about what will be needed to entice developing country participation. Only then will the odds for a comprehensive international climate change mitigation agreement start to improve.

Dr Stephen Howes is at the Crawford School of Economics and Government at the ANU. This analysis draws on a longer article available on his website and forthcoming in the Indian Growth and Development Review. It is also the March instalment of the EABER Newsletter, which may be found here [.pdf].