It has become progressively sicker ever since the last great financial crisis—the Great Depression—because it actively retreated from the challenge the Great Depression posed to its belief in the innate stability of the market economy. Now, as the global economy enters what could well be the Second Great Depression, economic theory is as useless a guide to how the economy actually functions as it was in the late 1920s.

Just one name is enough to establish that McTaggart et al’s claim about the health of economics is false: Hyman Minsky. Minsky long ago asserted that the true test of the relevance of a macroeconomic theory was its capacity to generate a Depression, since market economies had regularly found themselves in such a state.

Against such a measuring stick, every model discussed in a standard economics textbook, virtually every model in leading economic journals, and almost all the models that Treasuries and Reserve Banks around the world have constructed, are failures. They assume the economy tends to equilibrium (or worse, is always in it), making them incapable of explaining how a Depression—or even a recession—might occur. They are as useless as the theories of the 1920s which Keynes lampooned in his famous but misinterpreted statement about the long run:

‘But this long run is a misleading guide to current affairs. In the long run we are all dead. Economists set themselves too easy, too useless a task if in tempestuous seasons they can only tell us that when the storm is long past the ocean is flat again.’ (Keynes, A Tract on Monetary Reform).

Instead of being able to explain how this crisis came about, economists are reduced to blaming it on ‘policy errors’ by the Federal Reserve—precisely the claim that economists made about the last Great Depression.

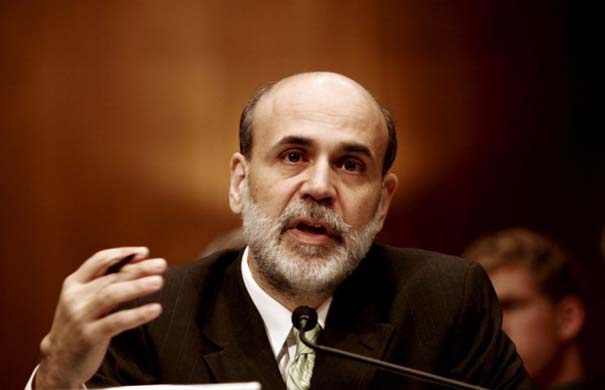

Ironically, one of the most egregious such statements was made by Bernanke at Milton Friedman’s 90th birthday, when he said ‘I would like to say to Milton and Anna: regarding the Great Depression. You’re right, we did it. We’re very sorry. But thanks to you, we won’t do it again’. Now Milton Friedman’s greatest disciple is becoming the whipping boy of neoclassical economists who are unwilling to consider the possibility that the model of the economy they share with Bernanke may be fundamentally flawed.

Will we have to go through a 3rd Great Depression before economists finally concede that it might not merely be ‘policy errors’ that cause such crises, but the innate workings of a credit-based market economy that they have manifestly failed to understand? On the record of articles like McTaggart et al’s (and a curiously similar recent article by another textbook author, Gregory Mankiw), this might well be the case.

As an economist outside the neoclassical mould, I predicted this crisis in December 2005, using a non-equilibrium model of Minsky’s Hypothesis that could generate a Depression. Such models have to become the mainstream in economics, which will require a revolution in economics: precisely what McTaggart et al and Mankiw are trying to forestall.

While I am open to your suggestion that neoclassical economics is dead, I am not quite clear about what it is you expect to replace the “credit-based market economy”. It seems to me that credit wasn’t such a bad thing until it became abused by unscrupulous predators and ignorant consumers whose behavior was encouraged by poor policy.

As early as 2001 I felt that the US economy was being mismanaged, rates were kept too low for too long, Greenspan let the air out of the tech bubble only to divert it into a housing bubble (which was perpetuated by an irrational obsession with home ownership on the part of US policymakers), etc. Consequently, I only kept a toe in the market.

And I didn’t need a degree in economics to figure all that out. 🙂

You’re misinterpreting my argument G.E. I was not calling for the replacement of a “credit-based economy”–that would be rather like King Canute commanding the tides to stop.

I am instead calling for the replacement of an economic theory that misunderstands credit and ignores debt, and its replacement with it with one that takes credit and debt seriously.

And yes credit can be sound (or sounder than it has become). Its abuse and the poor policy you point to were aided and abetted by neoclassical theory. A degree in economics, had you done one, would have made it harder for you to figure things out, so it’s no surprise you did the right thing without one.

Steve Keen is right on. In my 39 hours of undergraduate economics the closest thing I ever saw that sought to explain recessions was the concept of the inventories part of the “business cycle”. That of course does not explain why inventories or the broader economy get out of equilibrium. Of course the G and M parts of the GDP equation can be controlled by policy change, but I take it that what Steve is saying is that economists don’t have a clue to guide them except by looking in the rear-view mirror. That is, these changes are usually made to correct perceived disequilibrium that has some undesirable consequence, such as a recession or inflation.

The other relevant observation besides Keynes “in the long term we are all dead..” is that economists’ understanding of any part of the almost infinite complexity of an economy is “all other things being equal.” They never are. Real scientists can isolate various factors or values to try to eliminate casual as opposed to causal data, but social scientists can’t.

The most absurd aspect of this is when stock market analysts try to explain market behavior in terms like “profit taking.” Uh, somebody was also buying, right?

How many economists get Nobel Prizes for obscure microeconomic findings about some small aspect of market behavior? Greenspan himself gets at the heart of the problem with his mind-blowing explanation that he never expected business managers and investors not to base their decisions on the longer term viability of their corporations or institutions! That is an explicit admission that what lies beneath neoclassical economics, particularly the monetarist school, is ideology pure and simple.

The genius of our Constitution is that it was produced by men (mainly, alas) of the late 18th Century European Enlightenment, which rejected “revealed truth” and speculative theory for the study of man. A key aspect of their understanding of man was the establishment of a political system of checks and balances. Maybe those who call themselves neoclassical economists ought to look more closely at what the Classical economists of the late 18th Century had to say, who in fact called their field of knowledge Political Economy. This goes for all the other “ics”, “ists” and “isms” that rely on false ideological theories human behavior to function.

The fact that the world’s short term fate rests on economic decisonmakers whose world view is based a flawed understanding of human behavior is indeed disturbing. As Steve rightly corrects, this has nothing to do with the role of credit and debt per se, but how the system is supervised and managed.

Before we declare neoclassical economics dead, perhaps we should see whether the neoclassical economists in the Obama administration and elsewhere–a far more professional and mainstream group than those they replaced–can fix the problems. Early indications are that the problems are diminishing, either through their efforts or through the market-correcting mechanisms you virtually dismiss or some combination of the two.

I share some elements of Steve Keen’s arguments, but I am not sure whether he is overshooting in terms of declaring neoclassical economics dead. The current great recession and the impotence of conventional economic policies is an indication of some of the problems with the current economics.

I personally did not share the keen enthusiasm of McTaggart, Findlay and Parkin on the healthy status of the current economics, as shown in my comments on their article. However, though maybe not as healthy as McTaggart et al claimed to be, current economics may not be as sick as Keen portrayed.

Economics is dynamic and not static. It develops and evolves. Keynes made huge contributions to economics and the establishment of macroeconomics. It took more than 70 years to have a great recession and the avoidance of it becoming another great depression proves the usefulness as well as the limitations of Keynesian theories.

In that light, I am more a fan of Samuelson in terms of neoclassical synthesis. Yes, there is a need to have some new theories to further prevent great depressions or great recessions and to deal with them when they do occur. But those theories will not necessarily bury all other useful theories.

It may be the case that the new theories will be useful in managing and dealing with great depressions, then Keynesian deals with milder business cycles, then classical theories prevail when the economy is in some sort of classical equilibrium. I would go with such a neo Keynesian synthesis.

I find it hard how you can claim the “credit based market economy” is to blame for the financial crisis and not stop to ask the question…”Who provided the credit?”. You talk about Minsky saying economies have a tendency to fall into depression after “debt-financed euphoria”. Who provides the debt?

Your complaint is not about the market economy, but the government managed market economy. Credit expansion of the money supply is not natural to the free market, it is a creation of federal reserve system. The federal reserve system provides the credit that makes the entire system unstable.

When the federal reserve system lowers the market interest rate (or allows fraction reserves to expand) below the real interest rate, the new money becomes indistinguishable from real savings. Businesses invest thinking there are enough resources to complete the investments, a temporary credit boom emerges. When the reality that the resources were never there to begin with sinks in, prices rise, and the investments made in lieu of the artificially lower interest rate all go bust.

I do think neoclassical economics is dead, so is Keynesian economics and any other economics that calls for government management of the money supply and propping up of a broke fractional reserve system by the federal reserve system.