However, those monitoring progress, or its lack, now fear that hoping for even an outcome as ‘successful’ as from Bali (COP-13 in December 2007) is optimistic. and in Bali, despite the still shiny 2007 IPCC Nobel Peace Prize and the warm and worldwide acclaim of Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth, negotiations essentially failed.

Governments and negotiators fully understand that the future of the climate and of societies around the world, which depend on its benign ‘status quo’ continuance, are in jeopardy. The science has been conclusively stated and the consequences of inaction are clear.

So, if the Framework’s processes are unlikely to build a new agreement global enough and fast enough to reduce emission, and, much more importantly, to begin to address the issue of reducing the atmospheric burden of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases already in our atmosphere and inevitably pouring in from developing nations, what other strategies are there? Some advocate very strong economic measures such as a significant carbon tax that would make carbon-derived power more expensive than alternative energy. Others now champion peremptory government action: comparing the need to national railway building, whole-scale electrification, or war.

However, the majority of franchised electors seem, oddly, to expect a technological breakthrough ushering in a new era equivalent to Mr Ford’s car, which miraculously solved the problem of horse manure piling up on the streets of 1900s London. If we just hang on a bit longer, there will be a wonderful breakthrough and our problems will be solved without us having to change our lifestyles or forego the latest new gadgets this year. If this is our view, or at least how our leaders think we think, we owe it to ourselves to explore the degree of change any such ‘technology solution’ will have to have, say, for example, in Australia.

Before Bali, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s Fourth Assessment Report said that limiting the CO2 equivalent concentrations to 450 parts per million by volume by 2050 would only reduce the likelihood of exceeding 2 degrees C (deemed by many scientists to be the threshold to ‘dangerous climate change’) to 50-50. Even this unsatisfactory risk of unacceptable climate change requires all developed countries to reduce their emissions from 1990 levels by 25 to 40 per cent by 2020 and by 80 to 95 per cent by 2050.

In Bali, the newly elected Prime minister, Kevin Rudd, said he would, “Set Australia firmly on the path to achieving our commitment of a 60 per cent reduction in emissions by 2050”. Professor Ross Garnaut in his Review in 2008 went further and proposed that Australia increase its targets beyond those pledged by the Rudd government: ‘Australia should be ready to go beyond its stated 60 per cent reduction target by 2050 in an effective global agreement that includes developing nations.’ However, these exhortations have been ignored and the Emission Trading Scheme (ETS) offers at best 25 per cent reduction from 2000 (not the 1990 Kyoto base year) or, in the absence of an agreement in Copenhagen, emissions per cent lower than 2000 levels.

Australia is not alone in offering targets or in changing baselines: ‘China plans to cut carbon emissions intensity by 20 per cent from the 2005 level in 2010,’ Xie Zhenhua, China’s vice-director of the National Development and Reform Commission, told reporters on 22 September in New York. Still, the Rudd government is brave (or foolhardy) in its claims: ‘When it (the Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme) commences on 1 July 2011, it will guarantee that Australia meets its National Emissions Target of as much as 25 per cent of 2000 levels by 2020.’

Guaranteeing even this target, which is unsatisfactorily lower than called for by both the IPCC and the Garnaut Review, will require economic and social change faster and more extensive than any politician has yet mentioned. Methods of reducing greenhouse gas emissions include: massively reducing energy use, rapid introduction of non-fossil fuel sources, and the nuclear power route espoused by many northern hemisphere industrialized nations.

Carbon intensity is a measure of how much CO2 an economy emits for every dollar of GDP it produces. China achieves only around US$400 of wealth per tonne of CO2 emissions, while Australia and the USA are among the ‘top scorers’ in the world, creating US$2,000 of GDP per tonne of carbon. To decarbonise the Australian economy to a level consistent with the best offered ETS promised emissions reduction target of 25 per cent by 2020, Australia must reduce its economy’s carbon intensity by about half. While this might be accomplished by a variety of means, one characterisation is that it requires the equivalent of replacing virtually all Australia’s coal-powered electricity by a zero-carbon alternative. By 2020, Australia can choose to stop using coal-based power, go nuclear or access renewable energy.

Of Australia’s total energy consumption of around 175 gigawatts (GW) per annum, coal provided 26.4 GW of electricity in Australia in 2004. Consumption increased between 2004 and today, and is expected to continue to increase in the future. If Australia’s demand for electricity increases by 1.5 per cent per year to 2020 and was 58.3 GW from all energy sources in 2004, then an additional 15.7 GW will be demanded by 2020. Thus to deliver its ETS target Australia must either stop consuming 74 GW of electricity or create this from non-carbon sources.

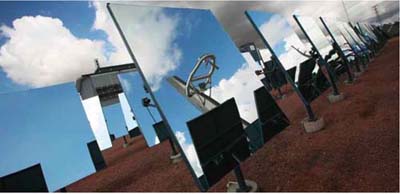

If this electricity were to be generated from solar plants instead of coal, what might we see, how will we know our ETS is happening, and what will it cost? Australia has been surprisingly slow to take advantage of solar energy: one can still observe many more solar collectors on home roofs in parts of (cloudy) Europe and the USA than in Australia. The best solar power plant operating in Australia today, in Cloncurry, produces a mere 10 megawatts (mW). but the best in world, the solar tower in Seville, Spain, generates 300mW at peak and there are plans in California for solar plants generating 500-600mW.

So, using today’s best technology, Australia would need around 230 solar plants to deliver its ETS promise by 2020. Australia would have to start in January 2010 and build two solar power plants every month until 2020. (Of course this is not the end as targets are tougher from then on). Still, just to 2020 the cost would be around US$414 billion, or roughly 0.52 per cent per annum of Australia’s GDP of US$8000 billion (in 2008). Before the global financial crisis this might have seemed large, but the last 18 months have muted reactions to such figures. The location and construction of any power generation plants would undoubtedly cause disruption to both the environment and to people, but since solar power is ‘clean’ perhaps concerns can be overcome quickly.

Climate change is real and requires very urgent government action around the world. While the scientific messages of urgency and certainty continue to be prey to a perplexing credibility shortfall, the responses of governments are now mired in post-Kyoto language of targets and timetables that completely miss the immense challenge of action now. Of the many proffered explanations of the international failure to act effectively, including the understandable self-interest of rapidly and newly industrialising nations, the sluggishness of democratic processes and the mass media’s failure to communicate the real climate story are among the most frustrating.

If the ‘guarantee’ stated unambiguously by government is honoured and Australia does not want 46 nuclear fission reactor plants, then we must expect construction of over 200 solar installations to begin by early 2010. Then Australia may have a chance of achieving its targets, which only guarantee a 50-50 chance of averting dangerous anthropogenic climate change.

The debate around Copenhagen is farcical. McKinsey published a report on pathways to a low carbon economy this year. As I read it, the difference between ‘business-as-usual’ and the ambitious goals proposed for a new climate treaty is that the treaty, which seems politically unrealistic, would give the world about five more years, 2030 instead of 2025, before reaching a dangerous greenhouse gas rate of 0.05%.

My view is that ocean based algae biofuel presents the single best opportunity for a technological fix for climate change through planetary engineering. If less than one percent of the world ocean was used for algae biofuel production we could replace all fossil fuels, provide local ocean cooling, develop major new fisheries and regulate the level of CO2 in the atmosphere. Algae biofuel production appears to be the only strategy with potential to remove more greenhouse gasses than total world emissions. Suggestions for this proposal are at rtulip.net.

Even if CO2 will be reduced from 350 ppm to 0 ppm, climate change will continue because what is happening has nothing to do with CO2 and greenhouse gasses.

The ice caps have been melting since after the peak of the last ice age and this phenomenon was never driven by CO2. The Earth has continually been warming since after the ice age.

Scientist are not talking about the role of water. Water has been changing from vapor to ice to liquid. Past thermal maximums have been caused by water rising up to the atmosphere, and ice ages have been caused by the precipitation of water from high concentrations of water in the atmosphere. Scientists should open their minds to the movements of water since times past.