But with nominal government revenues falling 12 per cent between 2007 and 2009 this situation could have been much worse. The major fiscal management problem in 2009 was a large draw down on the savings accumulated over previous commodity boom years. This included the injection of K1.7 billion (8 per cent of GDP) from trust accounts into expenditure.

Much of this additional expenditure was justified on the grounds of fiscal stimulation in the wake of the global financial crisis. The majority of funds were indeed allocated to new investments, underpinning a massive 60 per cent overall increase in development budget expenditure between 2008 and 2009. However, the size and speed with which this draw-down occurred suggests that it might have been done too hastily. With many sectors of the economy already operating at close to full capacity, this type of demand stimulus is likely to have some negative consequences on the economy, such as putting upward pressure on interest rates, generating higher imports and potentially crowding out private sector investment. The costs of the stimulus can seen in the Central Bank’s 9.5 per cent inflation forecast for next year. This will erode incomes, particularly diminishing the welfare of the poorest segments of society.

In 2009 PNG came one step closer to the commencement of Exxon Mobile’s $16 billion Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) project. To its credit, the government has continued to manage the myriad challenges associated with the venture—which many feared would derail the project before it commenced. Production is expected to begin in 2014, and the LNG project’s success will reshape the PNG economy and the government’s fiscal resource envelope.

Resource extraction comes with significant risks. The 2010 Budget highlights some of these, discussing the consequences of Dutch disease, and the inevitable adjustment costs associated with an appreciation in resource exports and the Kina exchange rate. As the Budget also outlines, many of these consequences can be minimised by careful fiscal management. Sovereign wealth funds can sterilise export earnings, and foreign debt can be repaid by continued budget surpluses — although the latter has proven in the past to be a less reliable option.

The consequences of large resource projects such as this manifest themselves in many ways, of which Dutch disease is only one small element.

As PNG becomes an increasingly resource dependent economy, it will have to remain vigilant against the negative patterns of political and institutional behaviour that are encouraged by large inflows of funds from resource extraction.

It is well known that the easy money which resource extraction brings, combined with a lack of accountability over fund usage, makes government finances highly susceptible to misuse and exploitation. This can breed a culture of corruption and undermine domestic institutional processes. Large resource rents can also remove incentives to reform other sectors of the economy. This means that growth can become siloed in resource extraction activities with limited positive spill-over effects for other, more labour intensive, sectors.

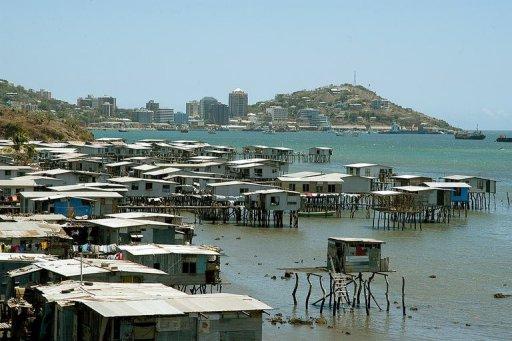

PNG’s history bears these risks out all too well. Those provinces which have recorded the largest earnings from resource extraction have been plagued by the weakest governance, the poorest levels of service delivery and in many cases by violence. In contrast, the resource poor areas of the country have tended to have more stable communities and better development outcomes – despite significant fiscal inequities.

Another danger is that, as with past resource developments, the LNG project will soak up a large proportion of the government’s scarce institutional capacity and that, because of this, important reforms will be delayed or abandoned. PNG still ranks as the least friendly and most costly business environment in Melanesia, and ranks far behind other regional competitors in East Asia. Law and order issues as well as land access constraints contribute to this situation. But the situation is also caused by sustained government policies related to the regulatory environment which have created a web of trade tariffs, tax concessions and operating subsidies to criss-cross all aspects of PNG business activities. Widespread wealth creation will depend on further progress with the microeconomic reform agenda.

As the government finds itself less dependent on external assistance because of the upsurge in resource earnings, PNG’s development partners will face a number of issues. Donors’ impacts on economic management and development outcomes will rely increasingly on the quality of their advice and the respect they obtain from the PNG Government, rather than on the persuasion of their cheque books.

Overall, 2009 was another small step forward for PNG. Fiscal discipline slipped as the government dipped excessively into its trust funds. This will have a number of negative economic consequences. With the large decline in nominal revenue this situation could have been much worse. Expecting politicians to resist the temptation of spending when an unprecedented opportunity for ‘fiscal stimulus’ is presented is probably holding the bar a little high for any country.

The discussion of resource revenue management in the 2010 Budget suggests that the Treasury Department at least is taking the potential risks from the LNG project seriously. Whether this translates into political action remains to be seen. PNG’s experience with past resource projects illustrates that the most important factor in transforming resource revenues into improved development outcomes is the strengthening of domestic accountability mechanisms at all levels of government. This must include a strengthening of the institutional arrangements guiding the allocation and expenditure of these revenues. Equally important is that the PNG government makes further progress on the microeconomic reform front. It must untangle the current web of domestic and international trade distortions, to unleash the productive potential of its own citizens.

This is part of the special feature: 2009 in review and the year ahead.

Aaron Batten completed his PhD in the Crawford School at the ANU, where he continues to be an Associate of the Pacific Program, and currently works in the Malawi Ministry of Finance.