As reported earlier, the US and some European powers attempted to bring financial pressure to bear on the Rajapaksa government to allow a humanitarian pause in the fighting to enable civilians to escape the war zone. Even though Sri Lanka was hard-pressed for cash and had gone cap-in-hand to the IMF, President Rajapaksa was able to ignore Western demands and fight the Tamil Tigers ‘into the ground’. He could do so largely because of other support from China, Iran and Saudi Arabia. Such support was unconditional, whereas Western support came garlanded with human rights considerations.

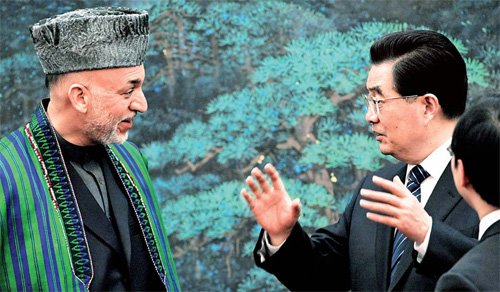

We now witness the spectacle of President Karzai resisting US and NATO demands concerning governance by flirting with US competitors, China and Iran. At the height of his differences with the US over his continuing failure to achieve higher standards of governance, he visited Beijing (his fourth such visit). He also welcomed US arch-rival, Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, to Kabul – the ultimate slap in the face to the US and its allies.

According to the People’s Daily, ‘China is seen as a key player in an international coalition seeking to secure and rebuild Afghanistan, particularly after US troops pull out.’ On his part, and without any apparent sense of irony, the Afghan Foreign Minister hopes ‘the security situation will allow Chinese investment to operate without any risks…’

A cashed up China, with foreign reserves of an estimated US$2.3 trillion, is active in giving soft loans and developing extractive and infrastructure projects throughout the region. China’s investment in Afghanistan includes US$3 billion in what is potentially the world’s largest copper mine, located south of Kabul. But it also has its eye on lucrative iron ore and gas prospects. China is concerned about Afghanistan not just for economic reasons, but also because of its key strategic location in respect of a number of Central Asian countries that ring the sensitive Xinjiang region of China.

China is intensively engaged in building infrastructure in Sri Lanka, supplying arms and giving credit. It is building deep-water ports in Burma, Bangladesh and Pakistan. It is constructing a gas pipeline from the Burmese coast to China. These activities have commercial logic for China. But they also provide a hedge in relation to Beijing’s concerns that its key oil supply lines might be threatened or interrupted during possible rising tension with India or the US. According to reports in the New York Times, China has also become deeply involved in developing Iraq’s oil provinces, under the very noses of the US, as it were.

The recent overthrow of the government in Kyrgyzstan, where the US has two bases of some importance to its Afghan strategy, must also have added to the sense of frustration in Washington. Although the new Kyrgyz government says the US can keep its bases for the time being, it is also apparently loyal to Moscow. Reports by STRATFOR say Russia has offered aid and that Moscow is likely to be the final arbiter on whether the US can keep its bases.

To strategists in Washington, it must increasingly appear as if the US is sacrificing ‘blood and treasure’ throughout the region while China, and to a lesser extent Russia, act as ‘free riders’, metaphorically licking their lips and waiting to pick up all the most lucrative pieces. And treasure is not as readily available to the US as it once was. The country is spending 4.7 per cent of its GDP on defence while it has a public debt of 87 per cent of GDP. It also needs to implement costly health reforms and refurbish its struggling economy. Although the US may be able to negotiate an exit strategy that spares it from the worst horrors of violent jihadi terrorism, it cannot necessarily garner regional influence and economic opportunity over the longer-term.

This situation could eventually cause a shift in US conservative opinion, which up until now has basically supported President Obama’s Afghan surge and its attendant nation-building attempts. Conservatives could start to reason that, so long as a settlement could be concluded in Afghanistan that would prevent further violent jihadi attacks on the US and its allies, the US should cut its losses on nation building and concentrate instead on the larger game – the emerging competition with China. Any such conclusion could also dictate a significant shift in the nature of US defence spending – away from the so-called war on terrorism and back to strategic competition.

Sandy Gordon is a Professor with the Centre of Excellence in Policing and Security (CEPS), RegNet, Australian National University, and a contributor at South Asia Masala.

This article first appeared here at South Asia Masala.

Re: But this costly involvement does not appear to have won the US and the West the influence they would expect to enjoy in the region.

Your insightful observation lies at the heart of the perceived Western capacity to determine the narrative and impose arbitrary solutions.

Western twentieth century meta-narrative used to impose its will in the third world was to create democracies, human rights and globalization to further its national interests.

Now the internal inconsistencies of western meta-narratives have become apparent with the rise of industrializing former colonies, socialized mass movements and failure of imposed and transplanted foreign institutions within indigenous cultures.

We now witness successfully industrialized developing nations have emerged before democracy and the US military have not succeeded in imposing coercive solutions in Vietnam, Iraq and Afghanistan etc.

History has shown, for example, that British and US industrialization occurred before full democracy was established.

The original European parliamentary templates in, for example, Indonesia and PNG acculturated to accommodate indigenous cultural norms.

China’s foreign trade and investment strategies in Africa better serve local developmental needs to the alarm and discomfort of Western interests.

The west is trapped by its own ideological straitjacket and hubris and will need time to adjust to the new geo-political realities.

Unfortunately, the economic and domestic political stresses with the US are reminiscent of the early stages of the Weimar Republic.

The EU is an incomplete construct and will be rent by internal political tensions resulting from the unresolved and unfolding GFC calamity.

These are troubling times and the declining reach of western meta-narratives cannot be reversed by even forceful means.

New thinking and paradigms are required.

We cannot follow King Canute and need to inform the Emperor that his is naked.