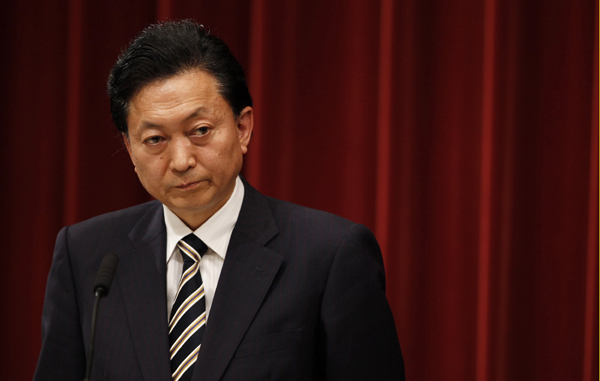

Moreover, there was definitely a political upside: a boost in the popularity of the Hatoyama administration, a lesson not lost on the prime minister as he battled to lift his administration’s dismal poll ratings.

The second round of GRU screening was conducted in two stages, in late April and late May. Under the microscope were programs run by two types of corporations that receive money from the government to finance their operations either wholly or in part: independent administrative corporations, or IACs (dokuritsu gyōsei hōjin) and public interest corporations (kōeki hōjin).

Amongst the stated criteria that the screeners (Government Revitalisation Minister Edano Yukio flanked by DPJ backbenchers and some private sector experts) used to guide their judgements were: does the program have appropriate objectives? Is there any need for an injection of treasury funds? How vital is the program compared with others when fiscal resources are limited? Can the program be undertaken by the private sector? Can the financial burden of the program be reduced?

The government’s unstated motives centred more on a desire to examine the nature of these corporations’ relationships with their supervising ministry, and in particular, their role in offering job placements for retiring bureaucrats (amakudari). The GRU’s radar was specifically attuned to any hint of collusive relations between corporations and ministries with respect to amakudari as well as the terms and conditions of ‘Old Boys’’ employment in these organisations, such as salaries and expenses.

IACs under the gun that are well known to outsiders were the Japan Foundation, JETRO, the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), the Agriculture and Livestock Industries Corporation (ALIC), the Japan National Tourism Organisation (JNTO) and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA).

In total, the GRU reviewed 151 programs in 47 IACs, recommending that 36 projects be abolished and a further 50 be scaled back. Amongst the programs recommended for abolition were: JAXA’s PR facilities (JAXAi); JNTO’s tourism services for foreign visitors to Tokyo; the overseas offices of ALIC; some National Institute for Agriculture and Food Industry Technology programs; lending activities by the Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Industries Trust Fund; loans to small and medium-sized homebuilders from the Japan Housing Finance Agency; and financial support to pharmaceutical bioventures from the National Institute for Biomedical Innovation. The GRU also recommended that the scale of JETRO’s international business support program be reduced.

In comparison with the relatively meagre returns from the first round, the GRU’s scrapping of 36 IAC programs produced a veritable bonanza, yielding more than ¥1.8 in assets for return to the national treasury. On top of this, at least another ¥1 trillion is likely to be obtained from surplus funds and other assets, such as securities, held by these bodies. GRU Minister, Edano Yukio, proudly referred to the ‘number of big stashes of buried treasure’ that the GRU uncovered.

In the second stage, the GRU’s screeners shone the spotlight on public interest corporations (both incorporated foundations and incorporated associations), looking at more than 70 organisations operating 82 programs.

According to research by the Asahi, more than 2300 former bureaucrats had found new jobs as executives or staff members in these public interest corporations – an average of 30 or more per group – while government subsidies and commissions totalled ¥145 billion, or an average of around ¥2 billion per corporation. GRU screening resulted in recommendations for the abolition of 38 programs, or almost half those under scrutiny, which would generate ¥4 billion in savings. Amongst programs recommended for abolition were the Airport Environment Improvement Association’s parking business, the Japan Center for Local Autonomy’s lottery-related activities, and the PR operations of various bodies including the Association to Promote International Cooperation.

Round two of the GRU screening process was driven by several broad government objectives. First, and most obviously, to generate additional funding for the DPJ’s own promised spending programs, particularly for expensive social welfare outlays such as the child allowance.

Second, to make progress on public sector reform, including eliminating amakudari, and advance the longer-term plan either to abolish public corporations, consolidate them, or shift their functions back to the government or the private sector.

Third, introduce more market competition into the public sector by eliminating the monopolistic and anti-competitive practices of public organisations, making them compete for government orders and terminating their monopolies in licensing and certification.

Fourth, play populist politics with a view to the upcoming election. Hatoyama used unusually negative language when referring to these organisations, expressing his hope that the GRU process would ‘wash away the filth’ that had accumulated in these organisations over the years.

Next on the GRU’s hit list are the Special Accounts in the national budget, which it will subject to a zero-base review. While the focus is usually on the General Account (GA), total expenditure in the budget’s Special Accounts is almost double the GA budget (¥176.38 trillion compared with ¥92.30 trillion in 2010).

Critics argue that the GRU assessments have no legally binding force and hence should be dismissed as just political slogans that help to release public frustration. Moreover they raise public expectations of politics in an irresponsible way because actual implementation is not certain at all. It is telling that the same phenomenon was evident with the government’s handling of the Futenma base issue, where the now departed Prime Minister Hatoyama publicly committed himself to seeking an alternative solution to the agreed relocation of the base, only to revert to the original plan in the end.