This judgment turns on its head the near universal consensus among the Big Three — Fitch, Moody’s, Standard and Poor’s — that the US government debt is by far the safest among the government debts.

Australia is rated AAA at the top, alongside countries like Norway.

The key difference between Dagong’s sovereign credit risk rating and those of its western counterparts is that it gives greater score to politically stable and economically strong emerging economies such as China, Russia, Brazil and India. Conversely, Dagong’s assessment incorporates a much dimmer view of the debt-burdened and economically stagnant developed economies such as the US, Britain, France and Spain.

According to the Chairman and Chief Executive, Guan Jianzhong, the essential elements of Dagong’s rating principles are ‘country’s governing ability, economic strength, fiscal position, foreign currency reserve and financial strength’. He believes that the difference between credit risk assessment of his organization and its western counterparts is due to the ideologically biased methodology used by Western credit agencies.

According to Dr Yu Yongding, senior research fellow at the Institute of World Economics and Politics of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, the controversial result that China has a higher sovereign credit risk rating than the US is understandable if one looks at it from a perspective of a country’s ability to service and repay its debt.

However, he cautions about an approach which relies heavily on benchmarks that are potentially favourable to the rating of China. This potentially compromises the objectivity and impartiality of a credit rating agency.

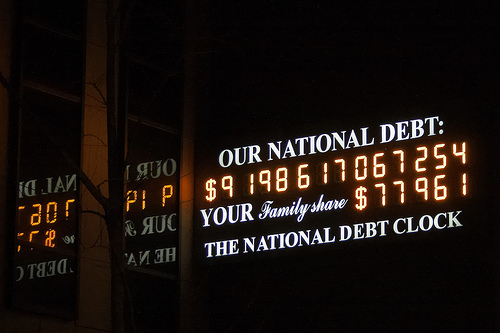

Yu further points out that, at the very heart of sovereign credit risk rating is the appraisal of a country’s ability to repay its debt and the most crucial indicator used in that appraisal is the ratio of debt to GDP. Currently, the debt to GDP ratio for Japan is 200 per cent, 100 per cent for the US by 2015, and by comparison, China’s debt is a mere 20 per cent of the GDP.

In addition to debt to GDP ratio, a country’s saving rate and savings structure are also important factors in influencing ability to repay debt. Using Japan as an example, despite its having a much higher debt to GDP ratio than that of the US, its high domestic saving rate greatly reduces its exposure to the volatility of the international debt market and the government is able to tap into the vast reserves of domestic credit at a relatively low cost.

Dagong’s new rating has been greeted with a degree of skepticism. The key problem relates to its methodologies. Though there are sound and rational reasons behind its new approach, it is far from being accepted as the appropriate norm by the international investment community. In addition, Dagong’s official connections through partial government ownership via such bodies as the Development Research Center of the State Council and the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences also raise an issue of objectivity and independence.

Right now is certainly a good time for Dagong to make a debut on the international credit rating market. Big Western agencies such as Moody’s and Standard and Poor’s suffered significant reputational damage through the harsh assessment of the credit rating of sub-prime mortgage assets before the global financial crisis. But for Dagong to establish a foothold in this competitive market, it has to demonstrate professionalism and impartiality.

Yu Yongding suggests that a regionally based credit rating agency in Asia can address the issue of the lack of Asian voice on the important issue of sovereign credit risk rating. Such initiative has also been touted by the former Governor of the Reserve Bank of India.

More strategically, Dagong’s initiative is yet another example of China’s increased presence and activism on international stage. Given China’s increasing economic and political strength, it is unlikely to remain content to be a regime taker. Beijing is increasingly demanding and pushing for an greater voice on international stage. In this context, the birth of Dagong is another small harbinger of China’s gradual transition from being a regime taker to the role of a regime maker.

Justin Li is principal of the Institute of Chinese Economics and a regular contributor to EAF.