But even if such an outcome is somehow staved off, Liu has made the work of the forces of tyranny much harder, and the prospects of the forces of political reform much brighter.

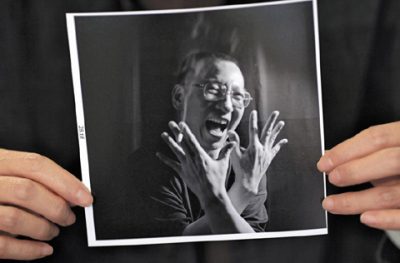

Liu Xiaobo is a former university lecturer in literature and philosophy, the author of books and articles; gaoled after the Tiananmen movement of 1989, despite his well-documented role in attempting to persuade the students to drop their radical postures, and despite also his role in averting a worse massacre from occurring. Gaoled again in the late 1990s, constantly under surveillance and long prevented from pursuing an academic career, Liu became a phenomenally productive columnist, able to publish in Hong Kong and other overseas media. With his writings under strict ban in China, he is largely unknown to the general public, though capable of creating waves in cultural and intellectual circles. In 2009 he and a circle of associates produced Charter 08, modelled on Vaclav Havel’s Charter 77. This document challenged political authority, demanding that it live up to its own stated political reform objectives. At the top of politics in China, there is evidence of division over political reform. Premier Wen Jiabao, head of the Government and a member of the Standing Committee of the Politburo, has called for the realisation of universal values.

Despite the attempts of Wen and others, a shallow understanding of universal values has been attached to a conspiracy theory that poses them as weapons in an effort by the West to contain and repress China’s rightful rise in the world. In his best-selling book, China Stands Up (2010), the writer Moluo, who once sided with ‘liberal’ voices close to Liu Xiaobo, sets out to settle accounts with the ‘May Fourth Movement’, the patriotic movement criticising the entire Chinese tradition that followed the Treaty of Versailles in 1919 (and, ironically, gave rise to the Communist movement in China).

Moluo claims that the May Fourth, now a tradition of counter-tradition, embodied the denigration of Chinese culture that had been a mark of Western imperialism since the Opium Wars. While not mentioned explicitly by Moluo, Liu Xiaobo’s writings are solidly in the May Fourth lineage. From as early as his first book, Xuanze de pipan [Critique of Choice], (1988), Liu’s ‘Chineseness’ has always been open to nationalistic attack on grounds of supposed ‘wholesale Westernisation.’ On one occasion, interviewed by the Hong Kong journal Kaifang, he stated that political reform was possible in China only if one imagined it remaining under colonial reform for 300 years. ‘I doubt 300 years would suffice,’ he added. Those who know Liu can easily imagine the ironic grin and chuckle with which he would have made this statement. Nationalist propaganda, unrelenting since the suppression of the Tiananmen protest movement, has created a generation in China that is utterly tone-deaf to irony and for whom Liu is quite literally a traitor (though they can’t explain why he would have advertised this so publicly before returning to live in his motherland).

The text of Charter 08, the document which more than anything else sealed Liu Xiaobo’s fate and led to his harsh 11-year sentence on Christmas Day 2009, is explicit in its appeal to universal values:

‘The Chinese people, who have endured human rights disasters and uncountable struggles across these same years, now include many who see clearly that freedom, equality, and human rights are universal values of humankind and that democracy and constitutional government are the fundamental framework for protecting these values.’

Attacks on Liu Xiaobo will inevitably link his ‘wholesale Westernisation’ with the universal values to which the Charter 08 document subscribes. His insistence that universal values really be universal — that the West itself be subject to its own culture of critical enquiry —will be swept aside. But there is a fatal weakness in the critique of universal values in China today. Something has to be offered in their place such as ‘Chinese values.’ So far nothing but ‘motherhood’ concepts like ‘harmonious society’ and ‘peaceful rise’ have been put forward. Social order, based at its core on a pervasive police state, and unquestionable authority protecting the interests of an opaque power elite are values that dare not state their real names. In any genuine debate they must fall before the universal values of Charter 08. If there is anything of value in them — say traditional Confucian ideas of meritocracy — these will survive genuine debate and become special applications of universal values. Meritocracy that arbitrarily arrests and imprisons will be thrown in the trash-can of history.

Universal values are only universal in a Platonic sense. They continually find concrete expression as societies, together with the economic and political systems, evolve and change. What is crucial is that a nation’s leadership articulate rather than impose its values. The adaptation of universal values to a particular context can be achieved only by the society as a whole. It is this that makes them universal. China has nothing to fear from genuinely universal values because they will at the end of the day be defined and enacted by Chinese people.

The regime quite literally gaoled Liu ‘because it could’. It will eventually release him for the same reason.

David Kelly is a Professor of China Studies at the China Research Centre, University of Technology, Sydney.

Liu Xiaobo does not deserve the Nobel prize – he conducted domestic political activity under foreign sponsorship, something illegal in most countries. In US law, FARA outlaws such activity.

The fact that Liu has received nearly a million dollars from the US government, via the NED, is a matter of public record. Liu’s conviction on subversion of state authority is also based on the accepted right by the state to preserve sovereign independence.

The Chinese court’s verdict on Liu, page 4 section 1 and 2 clearly established Liu’s foreign agent status through evidence of financial sponsorhip: Liu had no significant income other than payment from abroad for his political commentary (including abolition of China’s constitution in Charter 08), and his wife withdrew foreign remittance from their Bank of China account.

Would someone on the take from China advocating abolition of the US Constitution ever be considered for Nobel? Not a chance.

I don’t know Liu’s case. If this revelation is true, now the water has become mudded and the case more complicated.