But focusing on the award’s foreign policy implications risks obscuring the far more important domestic side to the story. The Beijing government’s major concern with regard to this prize announcement is not external, but internal, as it waits and watches to see how millions of Chinese people who would not otherwise necessarily have heard of Liu and his pro-democracy Charter 08 react to the news. And a week on from the awarding of the 2011 Nobel Peace Prize to Liu Xiaobo, only one thing seems to have emerged with any great clarity: How fragmented China actually is.

Almost as soon as it became politically correct to do so in the post-1978 period of ‘reforms and opening up,’ the Chinese government has craved Nobel Prizes. As part of a broader post-Mao yearning for international prizes and ‘face’ (for the Olympics, to qualify for the football World Cup, to enter the WTO), Beijing has desired a Nobel Prize for a Chinese person living, working and prospering in China, as nationalistic validation that the People’s Republic of China has made it as a modern global power.

But for as long as China has officially suffered from a Nobel Complex (nuobeier qingjie), this quest for glory has gone sourly for its rulers. Through the 1980s, for example, China’s establishment publicly pursued the literature prize. Nobel anxiety became an official policy issue that drew in politicians, writers, critics and academics, and generated articles, conferences and official delegations to Sweden. By the mid-1980s, however, it became apparent that the conformist literature most beloved of the Chinese state was not the avant-garde, non-establishment literature – by poets such as Bei Dao or Yang Lian – preferred by the Nobel Committee. Such non-establishment writers themselves actively aspired to a Nobel Prize, moreover, to challenge directly the party-state’s definition of ‘China’ and its culture. And it was, of course, Gao Xingjian, an exile writer and public critic of the Communist government, who finally took the prize in 2000. Only days before the announcement of his prize that October, a popular Beijing newspaper ran articles on China’s ongoing ‘Nobel Blues.’ Once the news of Gao’s Nobel broke, however, the government stonily responded that ‘the Nobel Prize for literature has been used for political purposes and thus has lost its authority’ and issued an immediate ban on publishing or discussing Gao and the Prize.

But beyond this crudely monolithic official response, the symbolism of Gao’s prize was intensely contested by Chinese observers. As the news broke across the global Chinese community on the internet, its significance was fiercely debated, with netizens expressing joy at a Chinese writer winning the Nobel Prize, puzzlement at the unfamiliarity of Gao Xingjian’s name and resentment that here was a Chinese writer, acclaimed for his global stature, that only readers outside China could enjoy. Responses were particularly ambivalent among mainland Chinese writers (who were, and remain, subject to the censorship that caused Gao to leave the country in 1987). Although there was no question of support for the Party-state nationalism apparent in the government’s reaction, many non-establishment writers refused to express approval of Gao’s award or identify with his literary achievement, criticising him for (allegedly) pandering to Western tastes for tales of Maoist trauma, or for being insufficiently ‘Chinese.’ Far from creating a rallying point of pride around which Sinophone authors could unite, Gao’s prize generated a nationalistic fight to stake claim to what Chinese literature was.

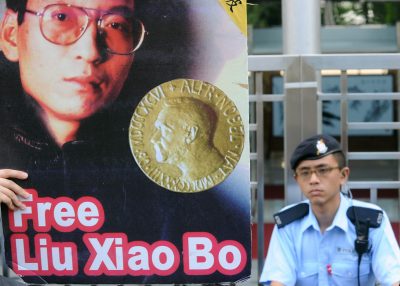

A close replay of Beijing’s earlier Nobel embarrassment took place on the morning of October 8, 2010. After a brief pause for reflection, the Chinese foreign ministry lashed out against the announcement: ‘The Nobel committee’s decision to award such a person the Peace Prize runs contrary to and desecrates the prize.’ Again, as in 2000, discussion was promptly shut down: Not only about Liu, but about all that year’s Nobels, as just-published stories on the Literature and Science prizes were swept off news websites and into virtual trashcans. In two anti-Nobel rants aimed at foreign readers, the government tabloid Global Times declared that ‘the decision is aimed at humiliating China. Such a decision will not only draw the ire of the Chinese public, but also damage the reputation of the prize.’ The Nobel Committee was blasted for ‘arrogance and prejudice,’ and for being part of an international conspiracy to undermine China.

Elsewhere, responses were more complex. Liberal Chinese netizens blogged and twittered that they were weeping for joy, and that the news brought the light of hope to those suffering in the ‘dark night of oppression since 1989.’ ‘A fine and upstanding Chinese citizen has won a Nobel Prize!’ commentators rejoiced. ‘Liu’s prize is exceptionally significant: it shows the whole world that China is a dictatorship, a country without democracy and guaranteed human rights. The Nobel Committee has given the Chinese Communist Party a big punch on the nose.’ On October 14, around a hundred jubilant scholars, authors, lawyers, editors and activists published an open letter to the Chinese government, requesting Liu’s immediate release.

Yet elsewhere, the response was more apathetic. While some foreign correspondents felt that the media crackdown on discussion of Liu Xiaobo was exceptionally harsh – hinting at the extreme anxiety of the leadership to prevent broader discussion of Liu’s ideas – other observers argued that Liu Xiaobo’s ideas did not chime with the more pragmatically everyday, economic preoccupations of many ordinary people. An informed Chinese journalist told me that, after an initial explosion of interest about Liu, China’s microbloggers went quickly quiet. This was not simply due to censorship, he felt. Instead, he doubted that anyone except for intellectuals knew who Liu was. In his view, the great challenge for China’s pro-democracy movement remained the chasm between urban, white-collar workers and rural labourers; Liu, he suspected, would be unable to unite the two constituencies. ‘Most people do not know or do not care,’ agreed another well-placed, non-establishment intellectual. ‘The impact of the peace prize will be relatively small, and the Party is very strong.’

Others again decided to see something in the Party’s conspiracy theory, viewing the award as a Western scheme to divide China: ‘This is an anti-China Western plot,’ one student microblogger was told by his classmates. An article on the mainland website Utopia – a meeting place for radical leftist, nationalist thought often bitterly critical of China’s current rulers – denounced Liu as a ‘dyed-in-the-wool traitor to the Chinese,’ for his 1988 pronouncement that China needed to be colonised for at least 300 years before it could progress to the level of a place like Hong Kong. ‘We should all spit on his Charter 08!’ ‘Keep him locked up!’ agreed one comment. ‘The masses should execute him!’ chimed another. Even Chinese dissidents – those suffering from precisely the same government repression that has locked Liu Xiaobo away – were not unanimous in their approval. Wei Jingsheng, the veteran democracy activist, complained that Liu Xiaobo was less deserving than others: He was too moderate and too ready to compromise with the Beijing government.

As with Gao Xingjian ten years ago, then, this Chinese Nobel Prize has generated a battle to define China and its key interests, permitting us to draw only one safe conclusion: That it is still impossible to gauge reliably public opinion in China today. Given heavy ongoing state control of traditional broadcasting and print media, judging the extent to which views generated by these media are in reality enthusiastically endorsed, passively accepted, or privately criticised remains unfeasible. It is just as hard to make any generalisations about opinion on the internet, where unrepresentative voices can dominate. It seems implausible that Liu’s prize will fail to have a significant impact within China’s borders – but we may not know for years how it will play out.

Dr Julia Lovell is an expert on the relationship between culture and modern Chinese nation-building. In 2006, she published ‘The Politics of Cultural Capital: China’s Quest for a Nobel Prize in Literature.’ Her next book, ‘The Opium War and Its Afterlives’ will be published in 2011.

Anyone who has some knowledge and sense of history knows that throughout its history, the Nobel Peace Prize has never been about PEACE (per se), is essentially, truly and fundamentally about promoting Western global moral authority. A bunch of people from North Western Europe, supported by the rest of the Western World, try to dictate and tell the non-western people what is moral and what is not. Sadly, it has been quite influential so far; quite a lot of people have been bombarded and totally fallen into this cleverly-masked fallacy without understanding the fundamental problems and contradictions of the world affairs. In this case, the Chinese government, or CCP to be exact, is told once again that, (after giving Dalai Lama the Prize in 80’s), you are an immoral and illegitimate governing party. Guess what? There are still many people who can do a bit of critical thinking and do not concur with this self-assumed ‘authority’. China will stay the course, go the distance and regain its rightly-endowed position, by that time, She will be a prosperous and democratic country, and its democracy will be firmly set on her own terms. The West can surely try to understand, it, but I believe the West will never do. Pretty unfortunate, indeed. I guess that’s why we have all these global conflicts throughout human history. Between peoples we just do not try to appreciate and understand each other. Anyway, the Nobel Peace Prize should instead be renamed: “Nobel Prize for Promoting Western Global Moral Authority”.

Really Jack? Another race apart are we? Whatever you think of the frailty of human institutions and their attempt to recognize universal goods, to the understanding of which the great Chinese philosophers have contributed in no small measure, this comment smacks of deep racism.

Dear Peter,

I don’t think it is proper for you to play the ‘race’ card here to counter my argument. It seems that your argument has very little technical sophistication to say the least – where do you smell the ‘racism’ in my statement?

Due to the limit of length for posting here, I couldn’t give as many exemples as I wished, e.g the Nobel Peace Price used as a soft power weapon against Soviet Union, or Eastern Bloc in the Cold War. That’s why I stated in the very beginning that ‘Anyone who has some knowledge and sense of history knows that throughout its history, the Nobel Peace Prize has never been about PEACE (per se)’.

Anyway, I am by no means intending to be racist towards the West. On the contrary, it’s the West who invented the concept of so-called ‘white man’s burden’, which is still very well latent and influential in the Western minds. This also well applies to the Nobel Peace Price case.

Cheers.