It is both intriguing and disconcerting that the death of one particular man, however iconic a figure he was and will remain, should trigger such a spate of imputations – as if the diverse 1.4 billion Muslims living in diverse circumstances that are in diverse ways and to varying degrees associated with this or that variety of Islam could possibly think and feel in any one single way.

What is ‘the Muslim world’? No agreed definition exists. The Muslim world that the Organization of the Islamic Conference says it represents, for example, is strictly official, consisting as the Conference does of 56 states plus Palestine. All of them are often referred to as Muslim-majority countries, but that description is incorrect. Of the 57 members, 10 do not have Muslim majorities, and two are borderline cases whose populations are apparently half-Muslim, half-not.

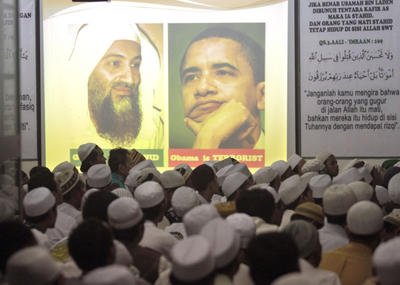

A radical Islamist in Lebanon regretted Bin Laden’s death because ‘the ummah’ — the global community of Muslims — was ‘in need of‘ a charismatic leader along Osama’s lines. But if a state-based and Muslim-majoritarian construction of the Muslim world is misleadingly political and demographically arbitrary, to cast that world in extreme-communitarian terms is to advance an even less probable claim: that the religious sensibilities of all of the individual Muslims on earth are sufficiently similar and strong to inform and sustain one single community of like belief and like behavior, including a shared ‘need’ for a new Bin Laden.

Muslims have no monopoly on wishfully romantic generalizations. Think of the Rorschach that is the largely Western and sometimes self-servingly invoked coinage known as ‘the international community.’ The point is not to stop using ambiguous terms, but rather to maintain an awareness of the complexities and contradictions they conceal, while at the same time recognizing their normative power.

Consider the sense in which belief in ‘the Muslim world’ is at stake in the currently contested destiny of the hopefully-named ‘Arab Spring.’

When Muslims incline their bodies toward Mecca in the act of prayer, or when they go there on the haj, they embody or enact the theological geography of the Muslim world. But the demographic center of that world is not Arab. It is Asian. One-fifth of Muslims are Arab, and most Muslims do not speak Arabic, notwithstanding their varying kinds and degrees of acquaintance with the Qur’an.

Developing countries in ‘the Arab world’ – another unitary construction – have long been categorized as less modern, less cosmopolitan, and less democratic than developing countries in other regions, including the Asian Muslim-majority states of Malaysia and Indonesia. A succession of Arab Human Development Reports, researched and written by Arab analysts and published by the United Nations since 2002, has documented this lagging status.

Asian Muslims do not have a ‘need’ to admire the Arab world. Yet their view of the Muslim world will likely be affected if and when current movements to reform the Arab world succeed. That success could, for some Asian Muslims, lessen the cognitive dissonance and attendant discomfort caused by the contrast between the valued status of the Arab Middle East as Islam’s historic birthplace and ritual hub and the center of Islamic learning, on the one hand, and its regressive politics and lack of modernity on the other.

If tyranny does finally yield to democracy, if Winter does not overtake the Arab Spring, Muslim democrats in Asia will have greater reason to believe in a Muslim world that is more than a superficial construct open to manipulation by simplistic analysts, solipsistic jihadists, and self-dealing elites.

The point is not to deny the resonance or utility of ‘the Muslim world,’ least of all its relevance for Muslims themselves. It is to acknowledge the complexity, diversity, and dynamic changeability of the reality behind the label – and to understand that the fit between the name and the named is itself in flux, as events alternately strengthen and belie the solidarity among Muslims that their supposedly singular ‘world’ implies.

Donald K. Emmerson heads the Southeast Asia Forum at Stanford University and an affiliated scholar with the Center on Democracy, Development, and the Rule of Law and the Abbasi Program in Islamic Studies. He is a co-author of Islamism: Contested Perspective on Political Islam (2010). This article was originally published here by the Asia Foundation.

Don,

A great piece, capturing the complexity of the situation, which is so often lost in reporting.

To say that the demographic centre of the Muslim world is Asian is true but meaningless. It is like saying that the demographic centre of the Catholic world is South America. What difference does that undeniable fact make to undermine the power of the Vatican? Will we get a Brazilian Pope any sooner? On the day that more Middle Eastern students go to Indonesia to undertake Islamic studies than Indonesians go to the Middle East for the same purpose, we will know that something has changed.

It is not meaningless to note the relative concentration of Muslims in Asia. My point was to disaggregate the “Muslim world,” which too often is obscured by overidentification with the “Arab world.” In that mistaken context, pointing out where most Muslims live is highly meaningful. Nor do I believe that we will only know “something has changed” if more Middle Eastern students go to Indonesia to study Islam than vice versa. Between the status quo and that hypothetical net eastward flow, all sorts of gradations of change along multiple variables at various speeds and with different implications are possible. My point was to raise one such possibility: that depending on how the “Arab Spring” turns out, and what its implications are for Islam and politics in the Middle East, how Indonesian and other Muslims think of the “Muslim world” could change. Asian Muslim opinions of the Middle Eastern part of the “Muslim world” are not frozen in time pending a fanciful net flow of students traveling east over those going west.