Even today, it is common to associate India’s ‘culture of corruption’ with the sense of entitlement produced by familial and caste loyalties — loyalties that are said to trump objective service to the state. The watchdogs of the state intended to deal with such abuses are allegedly also beholden to the hierarchical structure of society, and hence reluctant to bring high-status offenders to book.

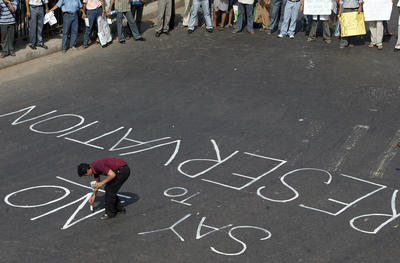

Others argue that in today’s globalised world, culture is a fluid phenomenon and the role of caste in India is diminishing. Economic liberalisation and urbanisation are said to have diluted the role of caste. Brahmin domination of foreign policy making has been overshadowed by India’s new ‘pragmatism’. India’s innovative reservations policies have worked to overcome the effects of caste, and the country’s vibrant press and fearless civil society are challenging and changing the landscape of caste, privilege and corruption.

But against these views there is convincing evidence of the persistence of caste, especially in rural areas. A study by the Department of Education, University of Lucknow, as reported in The Diplomat, found that in 40 per cent of schools across the sample districts of Uttar Pradesh, ‘teachers and students refuse to partake of the government-sponsored free midday meals because they are cooked by Dalits’ (former Untouchables). In rural areas, caste and sub-caste associations (khap panchayats) are often still dictating inter-caste marriage strictures, as well as occasionally carrying out horrendous so-called ‘honour killings’.

In his book, What’s Happening to India, Robin Jeffrey noted as early as 1994 that the vast unfolding of knowledge and information in modern India not only encourages equality but can also be used by political opportunists to reignite ancient ethnic, religious and caste divisions. The increasing salience of caste-based politics in states like Uttar Pradesh and Bihar lend credence to this view. In his recent book, Contemporary India: Society and Governance, Premchand wonders whether the policy on reservations enshrined in the Constitution has actually entrenched caste in Indian society.

So as India rises to power it is worth asking just how caste is shaping the modern nation.

One important question is how caste might adapt to the needs of a modernising economy. Will the fourfold varna, which defines the economic functions of major caste groupings (Brahmin: priest, scholar; kshatriya: warrior, administrator, king; vaishyia: trader, agriculturalist; and sudra: artisan, servant) translate into equivalent categories in modern capitalist society? In other words, will Indian society find a modern outlet for its traditional ‘genius’?

At the risk of falling into the bottomless pit of the caste–class debate and of committing a gross over-simplification, one could claim that caste has a partial, if ill-defined, role in the modernisation process.

For example, in Western India, banyia (merchant, trader and money lender) castes historically had relatively high status. In Gujarat they were wealthy and politically influential, while there was a saying: ‘he is as poor as a Brahmin’. Today these Western locations are the most advanced commercial and industrial areas of India. Similarly, today, Brahmins have used their intellectual prowess to progress from the bureaucratic functions assigned to them by the British to dominate key intellectual endeavours such India’s space, nuclear and other research institutions, and the higher levels of commercial enterprises. The lower agricultural labouring and artisan castes are being sucked out of the villages to power the factories and workshops. The middle castes either remain in modernising agricultural settings or, along with the kshatriya, populate the proliferating security arms of the state such as the police, paramilitary and military.

While these are extreme generalisations, they give us a relatively optimistic long term outlook on the role of caste in modern India. As occurred in Japan, these seemingly pre-assigned roles are likely to prove to be way stations towards a more fluid society. But that process is a long-term one.

Finally, what does the modern translation of caste tell us about how India is likely to engage with the world?

India’s worldview can be characterised as optimistic about the nation’s resurgent place in the international order. This optimism is likely dictated by knowledge of India’s great population and potential, and by the confident, even brash, views of a rising middle class, rather than by any vestigial notions of international hierarchy dictated by caste, as suggested by Tanham. In this regard, India is somewhat similar to China, with its determinedly nationalistic ‘netizens’. This sense of entitlement is driven not only by consciousness of size and potential, but also by the perceived need to rectify past wrongs.

Caste is definitely still a major factor in Indian society, but it is one that works in different ways in different places and at different levels of society. Despite the obvious depredations still associated with caste, the record is not necessarily all on the negative side of the ledger. It is a complicated picture as befits a complex and changing nation.

Dr Sandy Gordon is a visiting fellow at RegNet in the College of Asia and the Pacific at the ANU.

Caste is almost nonexistent no matter what anyone says, especially in major towns. How would writers get grants if they said so!

Women are attacked due to universal male power issues:labeled here as caste, inheritance, honor.

A low caste person can simply move and no one knows his caste, as in the past. Deep in some villages, caste can be a factor e.g. people refused food cooked by public toilet cleaners: both equally, totally valuable chores.

Brahmins, a tiny, mostly poor minority, were terribly vilified by evangelists for their own reasons. Colonizers routinely tarred anyone who was educated. So the real story is different!

Today class divisions count: someone’s education, speech, money, connections, his parents’ schooling, where lives. These define social interaction. Few city folk care about caste BUT they will note a person’s education and wealth, especially for marriage or as a business partner/employee.

EVERYONE in India supports affirmative action for low caste folk provided it is not gulped by the already well off. These generally have relatives who worked for the gov or some good company. This causes resentment among people refused college admission, financial aid or gov jobs, solely because their economically poor parents are high caste.

50% or more of gov jobs are reserved for low caste folk: as should be. This has changed Indian society wonderfully. Many senior gov executives will say proudly “I am a Dalit” and what could give more joy to India’s well wishers?