The discourse has thus far been driven by scholarly communities in Europe and the US, perspectives from other key regions such as the Asia Pacific are lacking.

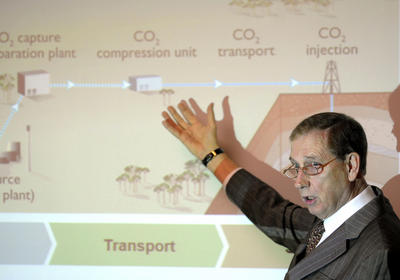

Geoengineering techniques can be split into two broad categories. The first category comprises techniques aimed at the removal of carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere, such as carbon sequestration through CO2 air capture and ocean iron fertilisation. The second category consists of techniques to reflect solar radiation, such as the injection of sulphate aerosols into the stratosphere to mimic the cooling effect caused by large volcanic eruptions. Advocates of geoengineering argue that it could be a useful emergency defence against environmental damage in the case of climactic shifts. Detractors argue that introducing geoengineering as the new Plan B to tackle climate emissions may create even greater problems, since the full effects of various geoengineering techniques are not well understood. Geoengineering could also be perceived as a moral hazard, as there is the possibility that it could decrease the political and social impetus to reduce carbon emissions.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is currently assessing, for the first time, the scientific basis as well as the potential impacts and side effects of geoengineering proposals in their Fifth Assessment Report, scheduled to be finalised in 2014. As such, the Asia Pacific region needs to participate in the debate by identifying and assessing the risks and opportunities of geoengineering techniques.

At least three initial steps deserve particular mention.

First is regional consultations to map the main national positions on the different geoengineering approaches among Asia Pacific countries that are likely to be at the forefront of deployment and/or impact. The Centre for Non-Traditional Security Studies, in cooperation with the Oxford Geoengineering Programme, is currently facilitating such a dialogue by convening a regional pilot workshop in Singapore in July.

Second is scenario-building in order to identify the governance demands of geoengineering. In particular, the following questions should be addressed:

- What processes do we need to govern geoengineering, from further research to potential deployment?

- What are the existing legal and institutional mechanisms to govern geoengineering research, development and potential deployment? What would be the optimal regulatory framework?

- How would we manage the uncontrolled use of geoengineering for peaceful purposes, for example, the pre-emptive use of solar radiation management techniques by a consortium of countries with threatened coastlines? How would we deal with intended or unintended negative effects?

- How would we define ‘climate emergency’ for the purpose of triggering the deployment of geoengineering technology?

- What are the criteria that would define the success and failure of geoengineering deployment? For example, how would we determine at what level of carbon dioxide (CO2) the deployment of geoengineering technologies should cease?

Third is public and civil society engagement to facilitate a regional dialogue on the known and unknown consequences of geoengineering

Advancing the development and implementation of geoengineering technologies will require a globally-coherent regulatory approach to the field. The current lack of any regulatory framework opens up the possibility that the technology could be applied unilaterally by single countries, businesses or even individuals, without concern for side effects or trans-boundary implications. It will be important to reduce the possibility of situations where there will be winners and losers associated with the implementation of any new geoengineering technology. The development and exploitation of geoengineering technology may therefore require that a set of governance mechanisms be established in accordance with the potential risks and benefits to societies across different regions.

With regard to a tentative set of normative rules and principles to govern geoengineering from research to potential deployment, geoengineering should be regulated as a global public good within a well-defined public interest framework. Such a public interest framework should be defined via broad public participation and consultation, globally and regionally. Geoengineering research should also be subject to disclosure and open publication, and there should be an independent assessment of the possible impacts of any geoengineering research enterprise. Further, geoengineering governance arrangements should be in place before the deployment of any new technology.

The limits of mitigation and adaptation in responding to climate change, coupled with the risk of reaching or passing tipping points in the Earth’s climate system, make it extremely difficult for policymakers to categorically exclude the geoengineering option as a potential Plan B for tackling carbon emissions. Decisions on the implementation and regulation of geoengineering may well be the call of our generation. The Asia Pacific needs to find its voice in the debate. Let’s argue and choose wisely.

Jochen Prantl is Senior Research Fellow in International Relations, Research Fellow of Nuffield College, University of Oxford, and Visiting Senior Fellow and Coordinator of the Energy Security Programme at the Centre for Non-Traditional Security Studies in the S Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University.