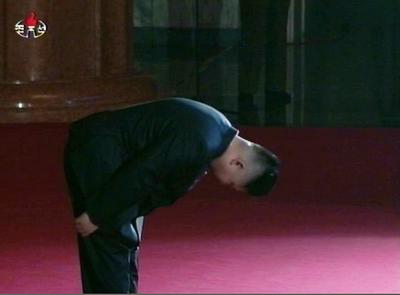

This scepticism is not without foundation. The new leader, Kim Jong-un, is young and inexperienced. He does not yet project his father’s power, let alone his grandfather’s charisma. His policy preferences are unknown, but his grooming period witnessed ill-advised initiatives on the economic and political fronts — from the botched currency reform to the tragic shelling of Yeonpyeong Island. Despite these shortcomings and questions, the succession process seems to be going smoothly. There is no evidence of near-term political crisis, confusion as to the new pecking order, popular revolt or systemic breakdown.

Why is near-term crisis unlikely? For the simple reason that the country’s political system is unified around the new face of North Korea, Kim Jong-un. He does not need to build charisma; his Baekdu bloodline is sufficient to endow his rulership with legitimacy. And his power base is solid.

Think of Kim Jong-un surrounded, and protected, by three inner circles. The first circle is the ruling family. The second is the Korean Workers’ Party itself, which has been going through a period of resuscitation in recent years. The revitalised network of Party members, who now carry cell phones and who are eager to travel abroad, see their prospects linked to the grandson’s success. The third circle is the military, which would be the logical competitor for power. But here, too, there is no sign of high-level disaffection, like that seen in many Arab Spring states. The military has been the primary beneficiary of the North’s ‘military-first politics’ campaign that Kim Jong-il initiated in 1995. And so far, the military has pledged its unfailing loyalty to Kim Jong-un.

But what, then, of the outer circle — the 20 million or so North Koreans not in the Party? Kim Jong-il was not beloved like his father, and pragmatic North Korean civilians are likely to take a wait-and-see approach to the new leadership group. Even those who may wish to rebel have no networks or organisations through which to do so.

Consequently, the chances of political crisis in the near term appear remote. But in the medium to longer term, the new leadership is likely to face a dilemma, and this should be the focal point of international responses to the transition process. It is a dilemma created by two mutually conflicting goals the regime has set for itself.

Pyongyang has been loudly promising its citizens that 2012 marks the year of North Korea’s emergence as a ‘strong and prosperous great nation’ (Gangsong Daeguk). Kim Jong-il managed to achieve at least one thing for North Korea — the ultimate ‘strength’ of nuclear deterrence. Now, it is up to his son to achieve the other half of the equation: prosperity. There have certainly been unmistakable signs of a push to improve the national economy over the past few years — from growing trade with and investment from China to revived plans for special economic zones.

But the issue at stake is whether Kim Jong-un can enhance North Korea’s prosperity without undermining the source of its strength — its nuclear weapons program. Food aid and foreign economic assistance are urgently needed to ensure a smooth path through the first year of Gangsung Daeguk. Comprehensive economic development would also require foreign investment, trade, and financing — all requiring an initial loosening and eventual lifting of the sanctions regime that surrounds the North Korean economy. Achieving this will require substantive nuclear concessions on Pyongyang’s part.

This transition from security-first to security-plus-prosperity will pose the greatest challenge to the unity of the North Korean political system. Elements in the military might oppose sacrificing their prize possession. Hardliners will argue it would leave their country exposed to an Iraqi or Libyan fate. Therefore, the path to getting the North over that hump must start now.

So, the essential question is, what should the international community do? The most prudent course for key regional players is to re-open or expand channels with Pyongyang. The better we know the new leadership, the better we can respond to events as they unfold. Seoul, Washington and Beijing should focus energies on drawing out North Korean officials as the leadership consolidates around its new core, Kim Jong-un.

Fortunately, the US has some modest positive momentum to build on in crafting this kind of proactive diplomatic outreach. The US and DPRK were engaged in substantive bilateral talks on humanitarian aid and denuclearisation on the eve of Kim Jong-il’s death. The timing is fortuitous, and Washington should make the most of these revived channels, signalling readiness to work with the new powers. US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton seems to be taking a measured, constructive approach to Kim Jong-il’s passing — an encouraging sign that the US will be persistent and proactive.

Seoul’s reaction is even more crucial, and delicate. The South Korean public is divided over inter-Korean relations, and President Lee Myung-bak takes a hit whichever way he steps. But there have been increasing signs of fatigue with a hard-line approach, and this president, who has proven his conservative credentials, is uniquely positioned for a kind of ‘Nixon-in-China’ moment. In fact, President Lee has sent a New Year’s message to Pyongyang, noting the South’s willingness to reopen talks and foster cooperation with the North. Nonetheless, Pyongyang’s response has been quite hostile.

Beijing may have the best model for handling North Korea, as Chinese realists spend less time thinking about scenarios of North Korea’s collapse, and instead keep diplomatic channels open while supporting economic engagement. China also has military-to-military ties with the North, and can exert some leverage when it comes to moderating military behaviour.

In an optimistic scenario, China, South Korea and the US could use this changing of the guard to embark on a coordinated engagement policy to normalise, and denuclearise, the Korean Peninsula. For years, political analysts and military planners have discussed ‘contingency plans’ in the event of Kim Jong-il’s death. But now, with no sign of chaos or collapse, we need prudent and realistic diplomacy that lays the foundations for progress.

John Delury is Assistant Professor of East Asian Studies at Yonsei University, Seoul, and a book-review editor for Global Asia. Chung-in Moon is Professor of Political Science at Yonsei University and Editor-in-Chief at Global Asia.