The South China Sea territorial disputes that led to the recent dilemma have traditionally been considered a bilateral issue, either between individual ASEAN member states and China, or between two ASEAN countries. Yet this understanding is biased and inadequate. The dispute involves six claimants: four ASEAN member states, China and Taiwan. Hence, if the dispute is considered within its broader context, with China’s ambitious claim encroaching on the coastal shores of other claimants, any resolution should first and foremost rest upon a multilateral consensus.

Only when a multilateral agreement is reached can bilateral solutions become feasible. Even those ASEAN countries without a direct interest in the disputes should keep in mind the benefits they gain from regional stability, and the cohesion and unity of ASEAN. Moreover, each of these countries has already committed to build an ASEAN community by 2015. This community must be built upon a common foundation, and develop with common goals and directions. The territorial disputes over the South China Sea are shaking this foundation, threatening the goals and security of the region. Hence, the territorial disputes in the South China Sea are not merely a bilateral matter, but should be a great concern for the whole of ASEAN.

There are two sides to ASEAN’s failure to issue a joint communiqué in Phnom Penh. On the positive side, it showed that ASEAN persistently seeks consensus, which is often regarded as a sign of unity within the organisation. Any action or statement delivered in the name of ASEAN has signified to outsiders that a consensus has been achieved within the group. The diversity of political structure, culture, ethnicity, religion and economic development within and among ASEAN member states, and the divergence of views over the South China Sea disputes, show that this principle will likely remain significant in the coming years if cohesion and unity are to be maintained and the dream of creating an economic community by 2015 is to become reality.

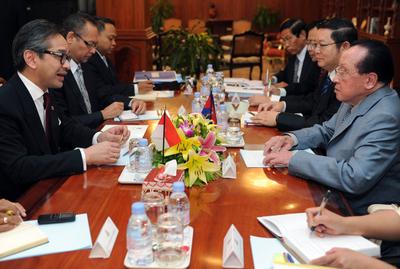

However, the other side of this principle might damage the dream. What occurred in Phnom Penh has led many to question the practicability of pursuing ‘one community with one fate’, and even the likely efficacy of the organisation’s performance after 2015 when this community is in place. It is also useful to ask why the consensus principle has been maintained. Apart from the positive significance, it seems the consensus principle has been maintained by some member states to prevent ASEAN from interfering in their internal affairs — almost all members have problems of human rights violations and ethnic conflict. Ironically, the consensus principle is now threatening the unity of the group when the national interests of one member state prevail at the expense of others. Cambodian diplomats made use of this weak point to prevent the group from raising a common concern about regional security in a document that was supposed to showcase ASEAN’s unity. To bypass a similar incident in the future, it is time for ASEAN to reconsider the meaning of the consensus principle.

Consensus is still necessary to maintain ASEAN’s unity, but it need not always be absolute. In any situation, consensus means that all members of the group can come to an agreement, so long as it satisfies the needs or interests of one party and does not harm those of other members. For a consensus to be absolute, however, all parties must share the same concerns and be willing to sacrifice part or all of their interests for the common cause. Many strands of international relations theory, borne out by much practical experience, would argue that absolute consensus rarely occurs when national interests are a critical factor. Instead, many now look toward to an approach based on compromise, or a non-absolute consensus. In this situation, consensus does not mean that everyone has to accept a decision; consensus should be understood as having everyone’s ideas heard equally and stated in the final document in an objective and unbiased manner.

The final communiqué at the 45th Ministerial Meeting should have been adopted and issued if the consensus principle had been understood in the non-absolute sense. Instead, it was wrongly understood and employed by one member to prevent other ASEAN states from passing a communiqué. Cambodia’s rather crude pro-China manoeuvre created a crack in ASEAN’s unity. Yet the recent failure to issue a joint communiqué should not be considered a hopeless experience; it should be seen as an opportunity to rewrite the consensus principle, which, to date, has been responsible for many ASEAN success stories.

Hai Hong Nguyen is a PhD candidate at the School of Political Science and International Studies, University of Queensland.

For those ASEAN members that perceive the South China Sea as not significant enough, contemplate these simple questions:

1) The 9 dash ( cow tongue ) map: has the Chinese government ever issued an official version with internationally standardized details showing locators and their meanings?

Does any one know accurately what are disputed vs. non-disputed areas?

2) The 9 dash map was actually revised from a 11 dash version,and first appeared in 1947. What assurance is there that China will not revise it a few more times to include parts of Cambodia, Thailand, Singapore since they share the same SCS?

3) China is aggressively escalating enforcement of EEZ’s that belong to Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines and Vietnam, and this may result in bilaterally negotiated loss of land/sea/territory and more. Will you abide by the results if China grants these countries part of your EEZ, in return?

4) For land locked countries of Myanmar and Laos: Chinese ” indisputable ” rights are history-based. What assurance is there that China will not find enough evidence of Chinese existence along your borders with China?

5) China did not get the land mass and population it has today by voluntarily stopping to grow.