We tend to over-emphasise the significance of personal factions and princelings, since neither tells us much about the policy preferences of individuals or the likely policy direction of the leadership overall. But to the extent that we do, there is factional balance in this group. Jiang Zemin apparently was able to insert more allies in positions on the Politburo Standing Committee (PBSC) than Hu Jintao, but Hu’s man, Li Keqiang is number two, a spot higher than usual for Premier, and ahead of supposed Jiang ally, Zhang Dejiang. But among the wider full Politburo there are several members who served in the Communist Youth League or are from Anhui and could be considered allies of Hu, most importantly, Hu Chunhua (Party secretary of Inner Mongolia) and Wang Yang (Party secretary of Guangdong). And some have worked closely with both Jiang and Hu, such as Wang Huning, who was originally brought to the Party centre by Jiang, but has served as head of the Party’s policy research office under Hu. And although Xi is surrounded by supposed Jiang and Hu accolytes, he is the top dog, and he immediately got Hu’s seat as Chair of the Central Military Commission. Hu looks like the loser, but it wasn’t a blow-out.

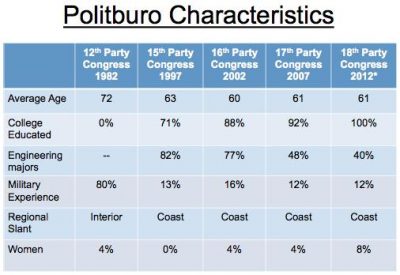

Whatever we think about any one individual or factional ties, we are seeing some interesting broad trends in the group. The average age of Politiburo members is unchanged, but the trend of growing diversity in educational backgrounds has continued. Engineering technocrats no longer dominate the body. Even majoring in Chinese literature isn’t an obstacle to getting to the top.

Some of the disappointment about the new group is that the two most likely advocates of serious political reform, Li Yuanchao and Wang Yang, didn’t make it to the PBSC. But you’d have to be beyond optimistic to believe the Chinese Communist Party’s top leadership is at all serious about democratisation. That is not on the cards no matter who is in the Politburo. There’s not a Gorbachev among them. We’ll see a range of reforms to improve how this system works (budget transparency, income reporting, more efforts to rein in corruption), but all of these tactics are being done to make this system work better, not prepare China to move toward another (multi-party democratic) system. If you’re sceptical they can make this system work better, they’re going to try and prove everyone wrong. Either they’ll succeed, or there will be a political meltdown.

There has been some talk about the ‘institutionalisation’ of the succession process and elite politics. Yes, if this means efforts to secretly negotiate an outcome minimally acceptable to all powerbrokers, and forcing anyone 68 or older into official retirement. But, beyond that, things appear much more fluid. Bo Xilai was brought down with a sledge hammer for apparently covering up a murder and being corrupt, and it is certainly possible that opponents of Wen used the foreign media (New York Times) to tar him for having a wealthy family. Negotiations were not neat and orderly and appear to have lasted through October. And many of the final decisions are inconsistent with recent practice: first, the PBSC went from nine to seven members; second, the premier’s rank was raised from number three to number two in the Party hierarchy; third, Xi assumed the Central Military Commission chair immediately rather than at a future plenum a year or two later (as Jiang and Hu did in 1994 and 2004); and, fourth, the number of women on the Politburo rose from one to two, a positive but unprecedented development.

I suppose someone could say all of this is consistent with ‘flexible’ institutionalisation, but that would be an excellent example of ‘conceptual stretching’.

Despite the Party’s likely continued tight control on the political wheel and the lack of institutionalisation, I expect more balance between encouraging market mechanisms and industrial policy. We should see sustained, though incremental economic reforms, which would be an expansion of trends begun over the past year: liberalisation of interest rates, continued bond market and stock market reforms, gradually opening the capital account, loosening prices for commodities and energy, and reducing monopolies for SOEs. At the same time, we should be under no illusion that industrial policy’s days are numbered. To the contrary, we will continue to see extensive intervention in most areas of the economy, particularly for ‘strategic emerging industries’ (SEI), as the government is not about to have faith that the market alone will push firms to invest in R&D and focus on moving up value-added chains.

Most refreshingly, though far from Obama-like, is Xi Jinping’s style. When he addressed the media, he spoke in non-Marxist terms about how he views the country and what his goals are. He made zero reference to his predecessors — Mao, Hua, Deng, Jiang or Hu, and he only mentioned ‘Socialism with Chinese Characteristics’ once. There was even some varying intonation in his voice, and he had a genuine smile. Goodbye, Robot Hu!

Scott Kennedy is Director of the Research Center for Chinese Politics & Business at Indiana University. His most recent book is Beyond the Middle Kingdom: Comparative Perspectives on China’s Capitalist Transformation (Stanford University Press, 2011).

This article was originally published here on The China Track.

Although most Americans view “democracy and liberalism” from the lens of direct democracy where people vote on policy initiatives directly, the United States’ form of government is, in fact, based on representative democracy in which people vote for representatives who then vote for the policy initiatives. This form of government is rooted in Madison’s Federalist idea which addresses the issue of how to control the negative effects of factions – a group of citizens whose interests are contrary to the interests of the whole community. Madison’s idea is to control the tyranny of the majority or the tyranny of the minority that imposing their wills on community interests. From this perspective, I don’t see how the Chinese form of government differs from the American one.

The most fundamental difference is separation of powers.