When North Korea found its own way out of the Six-Party Talks framework, China joined other member states in strongly denouncing North Korea’s provocative unilateral actions. China also voted for UN Security Council Resolution 1874 in 2009 to sanction Pyongyang. Yet, China’s top leadership since the North’s second nuclear test has seemingly reaffirmed the strategic value of Pyongyang for China’s foreign policy and national security.

In 2009, the year of North Korea’s second nuclear test, then Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao visited Pyongyang and promised to build a new bridge between the two countries over the Apnok (or Yalu) River as a symbol of economic cooperation. The following year, despite the North’s sinking of the South Korean corvette, the Cheonan, and North Korean artillery fire on Yeonpyung Island in the West Sea of South Korea, China has remained reluctant to publicly denounce Pyongyang. Last year, North Korea’s failed launch of a long-range rocket in April and its success in December resulted in China expressing ‘deep concerns’. However, there have been no signs of a decision to actively stop North Korea from continuing its missile or rocket program.

These actions and the policy approach of China in recent years clearly indicate that to Beijing, the relationship with North Korea remains its most important strategic alliance in East Asia, and Xi Jinping’s China can be expected to continue this policy stance.

Why has North Korea remained so strategically important to China in recent years and why is the new leadership in China following this path? The most important factor that has shaped the current relationship between China and North Korea is that the strategic environment in East Asia has changed rapidly over the past three years. In 2010, China became the world’s second-largest economy, surpassing the Japanese economy and confirming China’s G2 great power rivalry with the United States. The rapid rise of China in both military and economic terms, and its ubiquitous presence throughout the Asia Pacific region, has encouraged the United States to shift its focus to Asia with the announcement of its pivot to Asia in 2011. One of Beijing’s responses to this US policy stance has been to reinforce its traditional alliances with such countries as Laos, Cambodia, Myanmar and North Korea to counter-balance US advancement in Asia.

Second, as a country sharing a border of more than 1400km with North Korea, China has an interest in helping and supporting the North Korean regime to effectively control the border through internal stability. Any turmoil in the North Korean regime and social unrest caused by it would easily affect the neighbouring Chinese regions, in which a large Korean ethnic group already resides.

A sudden collapse of the current North Korean regime would also be a worst-case scenario for China since it would have to directly face South Korea, which has the strongest military alliance with the US in East Asia with 28,500 US troops stationed in South Korea. Under this circumstance, Xi Jinping and the new leadership in China would not dismiss Pyongyang even though North Korea may provoke South Korea and the international community again.

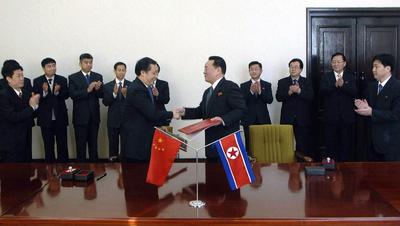

Shortly after Xi Jinping replaced Hu Jintao as China’s top leader in November, a delegation of high-ranking Chinese officials was sent to Pyongyang to meet North Korean leader Kim Jung-un and deliver a letter to him from Xi Jinping. It is assumed that in his hand-written letter, Xi Jinping invited Kim Jung-un to visit China in the near future. When they meet in Beijing, the strategic alliance of two countries will be reaffirmed and China will accordingly present a ‘gift’ — of economic benefit — to North Korea, as Hu Jintao did with Kim Jung-un’s father, Kim Jung-il.

It is natural to assume that China’s new leadership will also continue to deepen its economic ties with the North. In 2011, Pyongyang’s reliance on its trade with China accounted for more than 70 per cent of its total volume of trade. Resource and infrastructure development in North Korea, as well as the speed and scope of the North opening up economically, is now largely in China’s hands. China will utilise these economic leverages for its own national interests.

There may be small changes but nothing dramatic will occur if China continues to support the status quo in North Korea. There is little outsiders can do about North Korea under these circumstances. Amidst uncertainty caused by changes of leadership, or the start of second terms of administration in member states of the Six-Party Talks, the strategic value of the alliance between China and North Korea holds strong. This will remain critically important despite China’s expanding engagement and interdependence with the rest of the world — especially in economic terms.

Jeffrey Choi is a PhD candidate at the School of Politics and International Relations, the Australian National University and an Australian Government’s Endeavour Award Scholar.