Following the recent lapse of a US$3 billion currency swap contract and the lapse of a US$57 billion currency swap in October 2012, their bilateral currency swap is now equivalent to a mere US$10 billion, down from US$70 billion in October 2011. There is more behind this change than historical disputes or mere apathy. South Korea is starting to realise that its strategic and economic future lies more with China than Japan.

But wasn’t currency cooperation one of the success stories of regional cooperation in Asia, with Japan its most vocal proponent? After all, it was Japan who first proposed an Asian Monetary Fund, and the memory of the Asian Financial Crisis still haunts South Koreans, making them unusually supportive of currency cooperation.

Officially, both countries say that there was no particular need to renew currency contracts. The global financial crisis is over, and credit ratings for South Korea have improved greatly, returning to the pre-crisis levels. In 2010, South Korea let its currency swap arrangement with the United States expire without much negative impact.

Many analysts think historical disputes between South Korea and Japan explain the reduction in the value of currency swaps. This made sense in 2012, when the total value of agreements was reduced from US$70 billion to $13 billion. This downgrade came after then President Lee Myung-bak became the first sitting South Korean leader to visit the Dokdo Islands, a group of islets that Japan calls Takeshima. He then demanded the Japanese emperor apologise to those Koreans who perished while fighting for independence. In response, Japan’s Chief Cabinet Secretary and Finance Minister threatened a review of the size of its bilateral currency swap with South Korea, and finally on 19 October 2012 both countries announced that their currency swap agreement would be reduced. So last year, currency co-operation was clearly a casualty of disputes between the two countries over history.

But this year’s lapse is a different story. True, tensions still run high between South Korea and Japan over the issues of enforced sexual slavery and the Dokdo Islands. But South Korea’s new president, Park Geun-hye, has not visited Dokdo, nor has she demanded an apology from the Japanese emperor. It is unlikely that Japan is taking aim at the new president for the acts of her predecessor. And the size of the downgrade, US$3 billion, is relatively insignificant, especially if Japan meant to hurt South Korea. But if not discord over history, what would have led the two countries to reduce the value of their currency swap arrangements?

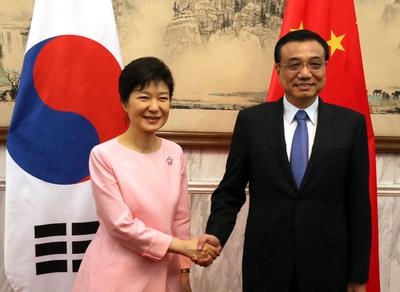

In early May, in accordance with the tradition set by her predecessors, President Park made the United States her first overseas destination. A month later, however, she broke away from the path trodden by her predecessors, choosing China over Japan as the destination for her second overseas trip. At the invitation of Chinese President Xi Jinping, President Park made a state visit to China in late June, where she was welcomed with unusual hospitality. In her two days in Beijing, President Park spent as much as seven-and-a-half hours with President Xi, conversing occasionally in Chinese and creating a bond with China’s new leader. President Park’s state visit to China, according to Yonhap News, ‘offers one of the best promises yet to upgrade relations with a nation that has the greatest leverage over North Korea and trades heavily with the South’. This is no overstatement. Relations between South Korea and China have improved greatly following President Park’s visit to China.

In the joint communiqué issued after the summit meeting, South Korea and China pledged to bolster cooperation on a wide range of issues. In particular, the two countries agreed to renew their currency swap contract ahead of schedule and extend it to 2017. This decision follows the 2011 agreement by both countries to double the size of their currency swap arrangement to US$56 billion. The countries are expected to further increase the bilateral currency swap and lengthen its duration.

President Park’s decision to visit China before Japan, South Korea’s decision to renew its currency swap deal with China ahead of schedule, and its decision not to seek an extension of its currency swap agreement with Japan are hardly unrelated choices; nor are they merely reactions to historical discords between South Korea and Japan. Rather, they represent new strategic thinking. Together, they suggest that South Korea is realigning its relations with major powers. Having leaned heavily toward the United States and, to a lesser extent, Japan in the past, South Korea is now balancing itself closer to China, its largest trading partner and also the country with the greatest influence over North Korea. By allowing its currency swap deals with South Korea to wither, Japan has only hastened South Korea’s diplomatic realignment and, probably, the internationalisation of the Chinese currency.

Intaek Han is Associate Research Fellow at the Jeju Peace Institute, an independent think tank located in Jeju, South Korea.

I think this article raises a good point that has been missed by many people over the years- that Japan and South Korea’s strategic interests are not as well aligned as others, particularly US commentators, insist that they should be. I agree that it is not simply historical and cultural issues that are getting in the way of relations. However, the risk to the ROK’s strategic autonomy inherent in this strategy will have to be managed very carefully going forward.

Intaek Han does however misrepresent the controversy over Lee Myung-bak’s remarks regarding the Japanese emperor, and the chain of events around that, at least from the Japan side. It was not the request for an apology as such that bothered the Japanese government, but the manner in which it was requested. He used a rather brusque tone of expression and essentially, unilaterally “uninvited” the emperor when the emperor himself had not made any mention of wanting to visit South Korea, and had not done anything on an interpersonal level to deserve LMB’s scorn (and in fact the Japanese emperor has defied Japanese conservatives by going on record as saying that there was a strong ancestral link between his ancestors and Korea). This was seen in Japan as Lee Myung-bak shamelessly using the emperor as a political football just after he had already inflamed tensions by visiting Dokdo.