Tensions between China and Japan have spurred nationalism in both countries and raised anew questions about each nation’s intentions in regard to the other.

It was only when France and Germany came to terms with each other after World War II that a stable, integrated Europe became possible. Achieving a similar comfort level in the Sino–Japanese relationship is critical for East Asia’s future.

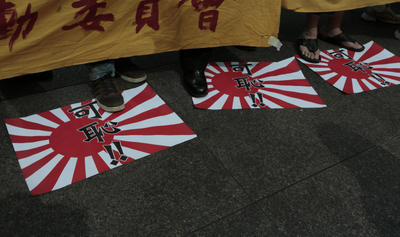

Yet Japan’s difficulty in accurately remembering the past and China’s difficulty in forgetting it results in a volatile relationship. Distorting the past complicates Tokyo’s efforts to become a more normal nation. The numerous apologies and billions of dollars in aid Japan has given to China since the normalisation of relations in 1972 are easily overshadowed by emotional nationalist reactions to Japanese statements that reimagine history.

Both Tokyo and Beijing need to take a deep breath and begin to think anew about how to move beyond this dangerous stalemate.

China often expresses concern as Japan enhances its defence capabilities, most recently when Japan unveiled a new helicopter carrier. Moreover, the US–Japan alliance is often cited by Chinese analysts as part of a strategy to contain China. Yet for the past 35 years, as China has transformed its economy, the US–Japan alliance has underpinned stability in East Asia and facilitated China’s peaceful rise.

If China has concerns about Japan’s defence spending now — at US$59 billion in 2013, Japan’s budget is dwarfed by China’s, which is estimated at more than US$120 billion — imagine what the regional security picture would look like to China if Japan were strategically independent from the United States.

While Japan has very capable air and naval forces and an increasingly adept missile defence system, it does not yet possess an offensive strike capacity. Even its new helicopter carrier is more suited to humanitarian or natural-disaster missions than offensive missions. Would China or Japan be more secure if Tokyo developed long-range missiles and nuclear weapons?

Viewed against the alternatives, the US-Japan alliance is better seen as a stabilising factor in the US-Japan-China triangle.

As the world’s third-largest economy and a global technology leader, Japan has the industrial and technological bases to develop offensive capabilities if it chooses to do so. Tokyo’s efforts are centred on defensive capabilities, constrained in part by a pacifist political culture that developed after the horrors of World War II, and by its Constitution.

But since the end of the Cold War, Japan has become a more equal partner of the United States, and it now seeks to share more of the security burden. The Japanese Constitution, effectively written by US representatives in the aftermath of World War II, prohibits collective self-defence and opinion polls suggest the Japanese public is divided on whether to revise or reinterpret it. What this means is that if North Korea fired a missile at the US – or China for that matter – Japan would be unable to use its full capabilities to help.

Prime Minister Abe’s overwhelming priority is to fix the economy. But Japan’s desire to be a more normal nation will not go away. After all, how comfortable would China be if its national constitution were written by a foreign power?

Even if Prime Minister Abe at some point in the future succeeds in revising the Japanese Constitution to permit collective defence, his highest strategic priority is strengthening the US–Japan alliance. This was demonstrable even in the title of the Joint Statement issued at the ‘2+2’ Security Consultative Committee in early October, when US Secretary of State John Kerry and Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel met with their counterparts, ‘Toward a More Robust Alliance and Greater Shared Responsibilities’.

Tokyo is in the middle of formulating its next five-year defence planning guidance paper, and even if Sino–Japanese relations improve significantly, Japan would still need to consider how to protect itself from threats from China’s ally, North Korea. Pyongyang continues to develop long-range missiles and has on more than one occasion fired test missiles over Japanese territory, most recently in December 2012.

As China argues, Japan should better reconcile itself with the horrors inflicted in the 1930s, as Germany has done. But China also needs to move beyond the easy temptation of anti-Japanese nationalism. Both Tokyo and Beijing would benefit from avoiding a cycle of action and reaction in their respective defence planning. The challenge is how to define a new type of major-power relationship between Tokyo and Beijing.

Robert A Manning is a senior fellow of the Brent Scowcroft Center for International Security at the Atlantic Council. He served as a senior counsellor from 2001 to 2004 and a member of the US Department of State Policy Planning Staff from 2004 to 2008.

A version of this article first appeared in the Global Times

The fundamental question is whether Japan and the US are willing to accommodate the rise of China. After all, the post WWII East Asia arrangement was setup without the participation of PRC. That means China will never accept this unfavourable Cold War legacy in which it was the object of containment.

1. The answer to that question I suspect lies in two other questions: Does the United States wish to have a militarized Japan, independent politically like for example, Russia or Brazil, or even India, having refused it the Asian Monetary Fund decades ago and snuffed out Mr Hatoyama’s East Asian Community talk more recently?

2. And having backed off from Syria, where United States had a dozen or so very friendly governments looking forward to participating, would it risk San Francisco or Los Angeles for the worthy albeit tiny Diaoyus / Senkakaus islets?

“After all, how comfortable would China be if its national constitution were written by a foreign power?”

This point is disingenuous and misleading. US statesmen (plus some important women) wrote the Japanese constitution, but it was ratified and amended by the Diet at the time and Abe’s efforts to revise it have failed to gain enough votes in the current Diet. His new strategy of reinterpretation is a way to circumvent democratic process and unilaterally impose the LDP’s agenda on the constitution.

Harping on US authorship is a convenient way to avoid the fact that the Japanese constitution as it stands today enjoys broad popular support. Why, Robert, would you adopt the same rhetoric?

1. Mr Manning raises a topical issue indeed; a couple of caveats follow:

2. As all know the United States policy making machinery is not a monolith, and in general a number of differing views exist at any one time. We now read that Mr Abe is “pushing for a looser interpretation of the country’s anti-war constitution”, rather than to “revise it” (http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/db42ec8e-3fab-11e3-8882-00144feabdc0.html?ftcamp=crm/email/20131028/nbe/AsiaMorningHeadlines/product&siteedition=intl&siteedition=intl&siteedition=intl&siteedition=intl#axzz2irJf72GO), and this what Mr Richard Armitage advises as the better course to the same goal, that is militarization of Japan (see: Armitage: Rebuilding Japanese economy is most important task facing Abe administration, Ashai Shimbun July 27 2013).

3. That Japan ought to have been held culpable in the manner Germany was is a fair point and the United States rather than Japan bears the entire responsibility for creating this imbroglio. The American view on this at the time of Japanese “surrender” (the Emperor failed to acknowledge the “surrender”, saying words to the effect that Japan had lost the war because of superior American technology/weapon, and apologised only to Japan’s allies- for losing the war that is), changed dramatically once fighting the “Red Menace” aka Communism was decided as the American priority. War criminals were speedily rehabilitated and those suspected of being “communists” even more speedily eliminated. Zaibatsu, undergoing eliminatetion were quickly rechristened Keiretsu, etc etc.

4. The outcome of Tokyo War Crimes Trials was given a “twist” by the well over 1000 page dissenting opinion of Justice Pal, whose view was that Japan’s war of aggression was no different from the West’s wars and colonization, and hence the Japanese were no more culpable or guilty. Justice Pal received the highest Japanese award from the Emperor for his services to Japan, and Mr Manmohan Singh considers Justice Pal’s work as the foundation of India-Japan friendship! Mr Pal, it has to be said had a point, but his views at least partly reflected Indian nationalism as symbolised by Mr Subhas Chandra Bose and his INA.

4. China did lose as many as 14 to 15 million dead in its war with Japan, of which the Nanjing massacre and the activities of unit 731 (see: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unit_731) are only two “highlights”, and this was a war that China simply did not initiate.

5. Mr Manning’s points are well made, but rather than continue here with a discussion of what is well known, I shall restrict myself to pointing out that Mr Abe does seem to stoke old emotions when he wishes to have aircraft he uses painted with “731”, or when he keeps repeating that the definition of “aggression” is an open matter, simultaneously with the desire to revise/reinterpret the constitution.

Robert Manning’s statements: “The Japanese Constitution, effectively written by US representatives in the aftermath of World War II…..how comfortable would China be if its national constitution were written by a foreign power?”

are somewhat of an oversimplification. Recent research, including that by John Dower, has established that the architects of the 1947 Japanese constitution were both American and Japanese and there was a lot of to-ing and fro-ing between SCAP’s government section and the Japanese sides, both government and non-government. Charles Kades’ grandson was one of my students at UNSW@ADFA a few years ago.

Another important point to make is that the Japanese people and the political mainstream have heartily embraced the 1947 Constitution, while it is the Japanese right who tendentiously argue that it is a foreign imposition.