It is a measure of the repair, stabilisation and forward progress in Sino–Indian relations that the two sides were once again able to discuss boundary-related business at a bilateral leaders’ summit. A Border Defence Cooperation agreement was signed by the two leaders, adding incremental innovations to an already rich menu of boundary dispute management protocols — ‘no tailing’ while conducting patrols, establishing a hotline between military headquarters and institutionalising more local commander-level meetings along the frontier are among the new measures. A Memorandum of Understanding on trans-border river cooperation that arguably contains Beijing’s most forthright acknowledgment of lower riparian rights to date was also initialled.

This moment of ‘strategic opportunity for [the] relationship’ only became possible after Prime Minister Singh and Premier Wen Jiabao worked on the sidelines of the 2009 ASEAN-led meetings in Thailand to limit bilateral tensions and charted a cooperative path ahead at the 2011 BRICS summit in China. But it is also a measure of the indifferent pace of forward progress in Sino–Indian relations that at their most recent meeting the two sides were unable to translate their productive exchanges on boundary dispute management into meaningful gains. An Agreed Record of the 16 rounds of special representative-level deliberations, let alone the outlines of a Framework Agreement for settlement, still appears to elude the two countries.

Implementation of some of the key clauses of their 1996 landmark boundary management agreement is predicated on forming a common understanding of the alignment of their disputed boundary. Harmonising perceptions on all but the most disputed points along the boundary is therefore imperative for peace and tranquillity in these areas, as well as the resolution of the underlying dispute.

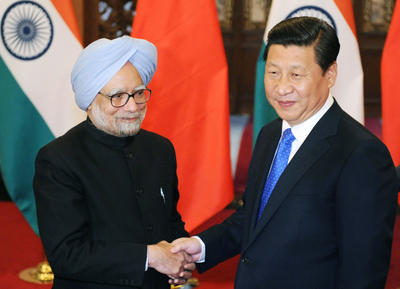

At first glance, it would appear that the Indians were the ones to drag their feet in Beijing. The Chinese were gracious hosts. A rare presidential banquet was thrown; Li Keqiang even provided a tour of the Forbidden City for Manmohan Singh. The Indian prime minister’s office, by contrast, had to haggle with the White House to secure a working lunch with President Obama earlier this September. Further, Beijing seemed eager to deal; Foreign Minister Wang had likened the exchange of premier-level visits in 2013 — the first such occurrence since 1954 — to sowing seeds in spring and reaping the fruit in autumn. At the summit, the Chinese side was determinedly forward-looking, exhorting New Delhi ‘to stand tall and look far’ and uttered nary a word against their visitors.

Yet the summit failed to harvest significant gains that would help to resolve the boundary dispute. Prime Minister Singh appears incapable of unilaterally extending a hand of friendship to China in the tradition of Jawaharlal Nehru, Rajiv Gandhi and Atal Bihari Vajpayee, each of whom faced longer odds in the years leading up to their successful visits in 1954, 1988 and 2003, respectively. But to simply blame the Indian prime minister’s lack of purposefulness is not altogether fair.

New Delhi remains skittish about Chinese intentions on the border following the Depsang incursion earlier this year, when a lightly armed group of soldiers established a token — and temporary — position on the Indian side of the declared Chinese claim line for the first time since the war of 1962. The incident was contrived by Beijing, in part, to establish the Singh government’s commitment to bilateral relationship management, and to showcase a successful example of such management to audiences further east and southeast. The Indians haven’t seen matters in quite the same light and continue to seek reassurances as a precursor to negotiations on the boundary issue. The Indians have even gone so far as to trade their withdrawal from Western- and Japanese-led schemes to contain Chinese power in the Indo-Pacific with China’s acquiescence on issues of bilateral concern to New Delhi — political quiet on the border, foremost among these.

Devising a set of detailed rules that breathes life into the recently signed Border Defence Cooperation agreement is the next order of business. The topic of territorial incursion has served its purpose of focusing Indian minds on the cost–benefit equation of accommodating China’s strategic interests in the Indo-Pacific. Beijing’s episodic transgressions along the unmarked frontier are therefore expected to be gradually reined in. A push to formulate a mutually acceptable resolution is also likely to emerge. On two prior occasions — in 1960 and in the late 1970s — New Delhi failed to build upon principles-led offers of settlement based on maintaining the status quo; in 2005 it was quick to seize the Chinese initiative and draw up a consensual set of flexible political parameters to guide boundary settlement. New Delhi would be well advised to again stay attuned to Chinese hints in the period ahead.

Sourabh Gupta is Senior Research Associate at Samuels International Associates, Inc., Washington, DC.

Sourabh Gupta’s sharp analysis of Manmohan Singh’s visit to China is very persuasive. One should also note, however, that the Indian Prime Minister visited Russia before going on to China. The Russian leg of his travel drew from the normally rather impassive and low-key octogenarian some quite hyperbolic statements that were not echoed in China. He said, for example, that “no country has closer relations with India and no country inspires more admiration, trust and confidence among the people of India than Russia”. Singh also described his country’s relationship with Russia as “a special and privileged strategic partnership”. This contrasts with his later comment that he was “reasonably satisfied” that China’s leaders were as serious as India’s in ensuring peace and tranquillity on the India-China border. In a joint statement, Singh and Putin made a thinly-veiled criticism of Pakistan in a section on terrorism by asserting that states which sheltered terrorists were as guilty as the perpetrators of terrorism. This would never appear in a Sino-Indian declaration. Manmohan Singh praised Russia’s recent role concerning the issues of Iran and Syria, and argued, no doubt correctly, that the two countries had similar approaches to Afghanistan. Even after discounting for the element of diplomatic courtesy in these statements, it seems clear that India and Russia have closer views on a wide range of international questions than India and China have. If Rahul Gandhi succeeds Singh as prime minister, he too is likely to give considerable priority to Russia, if only out of loyalty to his grandmother, Indira, whose closest foreign ally was the Soviet Union. In remarks that he made recently on the twenty-ninth anniversary of Indira’s assassination, Rahul showed how much that event still affected him. His BJP rival, Narendra Modi, will likely be no different. He has rarely had a kind word for China. Yet what impact the respective foreign policy orientations of Gandhi and Modi, one of them as prime minister and the other as opposition leader, will have on progress on the India-China border issue remains to be seen.