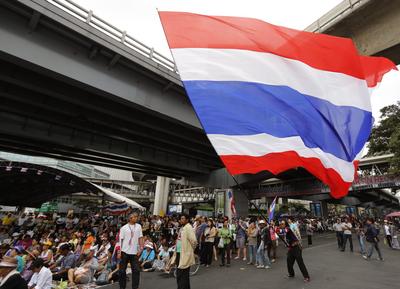

The use of the red, white and blue of the flag appeals to an emotional attachment, to a sense of patriotism, as if protesting were not merely a social or political choice but a national duty. When Princess Chulabhorn appeared in a photograph on social media with a Thai-flag ribbon in her hair, she justified the move as an expression of patriotism, undertaken because ‘I love this country’. How can an opposing group, which nevertheless feels the same level of patriotism, compete with such evocative national imagery? Use bigger flags? Sing louder renditions of the national anthem?

The use of the national flag is also a powerful signifier of the gravity of the situation, as the protestors see it: the wellbeing of the nation is at stake. As the protestors have effectively cast themselves as defenders of the nation, to oppose their aims or question their grievances is by extension to be un-Thai, unpatriotic, even insurrectionist. Competing versions of Thai nationalism between pro- and anti-Thaksin forces emerged after he assumed the premiership in 2001. Both sides have claimed to uphold ‘authentic’ representations of Thai national identity and regularly accuse the other of being ‘disloyal to Thainess and thus excluded from the national community’. The current protests feature this same ongoing contest over Thai political and social identity, with nationalism exploited as a means of legitimising certain actions and political principles.

Protest leader and former deputy prime minister Suthep Thaugsuban has sought to play to the nationalist drum beat in order to secure protest momentum and keep conservative factions onside, such as the People’s Alliance for Democracy (PAD) and the Network of Students and People for Reform of Thailand. His nationalistic shtick involves calling on Thai ‘patriots’ to protect the nation against all manner of invented threats, including Thaksin’s alleged plans to overthrow the Thai monarchy and install himself as head of state. On 11 November 2013, Suthep sought to capitalise on any potential surge in nationalist-inspired activism by announcing plans for a three-day nationwide strike on the same day that the International Court of Justice delivered its ruling on the territorial dispute between Thailand and Cambodia concerning the area around the Preah Vihear temple (a ruling which ultimately proved inconclusive). The territorial dispute has long provoked strong reactions among ultra-nationalists in Thailand, including the PAD.

The rhetoric of various speakers at protest rallies has increasingly taken on a xenophobic edge. On 26 December 2013, one protest speaker at a rally in central Bangkok claimed that paid Cambodian mercenaries were among the police who clashed with protestors earlier that day — an accusation given more significance since Thaksin is regarded as an ally of Cambodian prime minister Hun Sen. Suthep also bought into such anti-Cambodian sentiment by claiming that Cambodian gunmen were involved in the killing of leading protest figure Suthin Tarathin in Bangkok on 26 January 2014. This brand of xenophobic rhetoric is a common tactic of nationalist orators wishing to inspire domestic solidarity with a cause or identity by singling out some foreign ‘other’ as an object of denigration. Protest leaders in Bangkok may also prefer to blame bloodshed on outsiders in order to avoid confronting the painful reality of Thai-on-Thai violence.

The ardent nationalist sees no grey area between black and white. It is either ‘us’ or ‘them’. This false dichotomy is exacerbated by Suthep, who has emphasised the zero-sum stakes of the current political crisis, declaring that only one side can win and ruling out negotiation or compromise. In order to perpetuate the simplistic ‘us’ and ‘them’ division, any ‘third way’ which may dilute or undermine the core contentions of the anti-government forces must necessarily be dismissed as a pro-Thaksin ruse or, at best, the product of an insincere or insignificant minority. Thus when protestors began appearing on Bangkok’s streets wearing white and expressing support for the 2 February 2014 election they were collectively dismissed by anti-government media as ‘nothing more than Thaksin’s supporters’. As one attendee at a so-called white shirt gathering put it: ‘people are making you take sides. If you aren’t “yellow” then you’re “red”. Everyone thinks that “if you aren’t with us then you’re with the other side”. And this makes things difficult’.

In the current climate, in which anti-government protestors have called for the suspension of the democratic process, a more enduring and inclusive brand of civic nationalism, in which national identity is centred on a collective subscription to a set of civil and constitutional rights, seems unlikely to arise.

David Hopkins is a researcher based in Thailand and Melbourne, Australia.