This dream involves a ‘great revitalisation of the Chinese race’ by building a rich and powerful nation that is prosperous and happy. The party announced that it would promote the noble-minded enterprise of peace, tolerance, international trust, justice and cooperation. Yet, in security and diplomacy, political reports from the 18th Party Congress have emphasised building ‘powerful armies in accordance with [China’s] status in international society’ and that China should resolutely defend its maritime resources and ‘build a strong maritime nation’.

This line has led to an extremely delicate balance that Xi must maintain between international cooperation and a hard-line foreign policy. But as long as China’s priority is to become a great power, it is expected that strengthening national defences and protecting resources will be prioritised.

Ten years have passed since China became the second-largest economic power in the world, and over this time the country has also rapidly strengthened its military muscle. Following the increase of economic and military power and the heightened self-awareness as a superpower, political leaders, think-tanks, scholars and young people have started to argue that China’s diplomatic strategy taoguang yanghui (biding one’s time while strengthening oneself) should be abandoned.

China over the past few years has increasingly asserted its ‘core interests’, in the South China Sea, and is embroiled in territorial disputes with South Korea, Japan, Vietnam, Malaysia, the Philippines, Brunei and Taiwan.

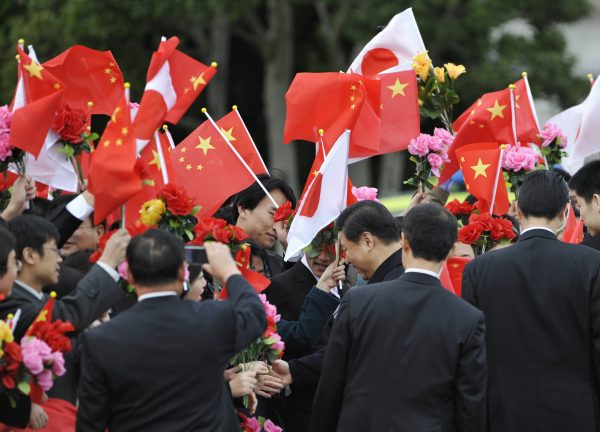

China’s shift from passive diplomacy was first highlighted in its dealings with Japan. China took an extremely hard-line diplomatic stance over the maritime collision in disputed waters near the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands in September 2010. After a Chinese trawler collided with Japanese coast guard patrol boats, China summoned the Japanese ambassador to Beijing six times (and once at midnight). Communication and tourism between the countries was seriously affected, and official meetings were cancelled. Vigorous protests broke out in both China and Japan—and China issued a travel warning for Japan after Chinese tourists were attacked in Fukuoka.

During this time Wang Jisi, Dean of the School of International Studies at Beijing University and one of the top brains at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, had maintained that taoguang yanghui was still valid and that ‘things should proceed in a discreet manner’. However, he changed to a more aggressive tone after Japan’s nationalisation of the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands in 2012, saying, ‘now, the occasion to use taoguang yanghui is only limited to when we refer to the attitude toward the US’.

A clearer picture of China’s vision for the 21st century international order was put forward by President Xi Jinping at his meeting with President Barack Obama in June 2013. He proposed a special or Group of Two (G2) relationship of superpowers and started to demand that the US recognise their relationship as the only relationship of world superpowers. Obama did not make any comment on this, but China would repeatedly demand it going forward.

At this same meeting between Obama and Xi Jinping, Xi also stated, ‘in the Asia Pacific region, there remains broad space that China and the US can share’.

The way that China has treated its relationship with Japan starkly contrasts with its relations with the US. In October 2013 senior Japanese statesmen, including former prime minister Yasuo Fukuda, gathered in Beijing and met Chinese senior officials in order to break the stalemate in the bilateral relationship. In the meeting, Tang Jiaxuan, chairman of the China-Japan Friendship Association (and a former member of the State Council) insisted that ‘Japan should clarify whether it stands on the Western world or Asia’. This is in line with comments by hardliner Yan Xuetong — that if Japan defines itself as a Western country there will be fewer ‘shared interests’ — and is related to the idea of a ‘Greater China Zone’, which China has been promoting as it extends its influence in economics, politics, culture and the military.

But here there is a paradox. The more China emphasises the ‘China model’ and the theory of ‘China’s uniqueness’, the more it conflicts with universal, widely accepted concepts in international society. If this is the case, the world will not accept the ‘China model’ or the theory of ‘China’s uniqueness’ even if China does catch up with the US in an economic and military sense.

China took the same path as other developed nations, of modernisation and industrialisation, by fully leveraging the advantages of being a developing country.

If China accepts reality and agrees to developing the current international order, rather than trying forcefully to create a new international order, international society will welcome it. China itself has expressed the need for such a framework.

Former Chinese president Hu Jintao asserted that ‘injudicious use of force does not create a beautiful world’. This statement positions China’s path of survival in the current international order. Hu Jintao continued: ‘We advocate the spirit of equality, mutual trust, tolerance … Cooperation and “win-win” mean to advocate the idea that all humans share the same destiny, pay attention to other countries’ legal rights while pursuing his/her own country’s interests, work together to overcome difficulties, share rights and responsibilities, and increase common benefits’.

This is in line with China’s position since the end of the Cold War, emphasising the principle of international collaboration. In this argument, Hu advocates an international strategy in which China should contribute from the universal perspective, not from the perspective of the theory of ‘China’s uniqueness’.

If China can lead the new international order, accepted and respected by other countries, it would fulfil the first criterion for becoming a true world leader.

Satoshi Amako is Professor and formerly Dean of the Graduate School of Asia Pacific Studies at Waseda University in Tokyo.

This article appeared in the most recent edition of the East Asia Forum Quarterly, ‘A Japan that can say ‘yes’’.

Really insightful and clear-cut!