A possibly more decisive unknown electoral variable is not what the opposition parties will do, but what New Komeito voters will do. Under the Japanese lower house’s mixed system of single-member districts (SMDs) and a proportional list, the LDP and New Komeito have often negotiated to not run candidates against each other in some of the SMDs. But there is very strong opposition to many of Abe’s policies among the New Komeito base and it is unclear if these voters will be able to hold their noses and vote for LDP candidates in the single member districts as part of the traditional LDP–New Komeito quid pro quo.

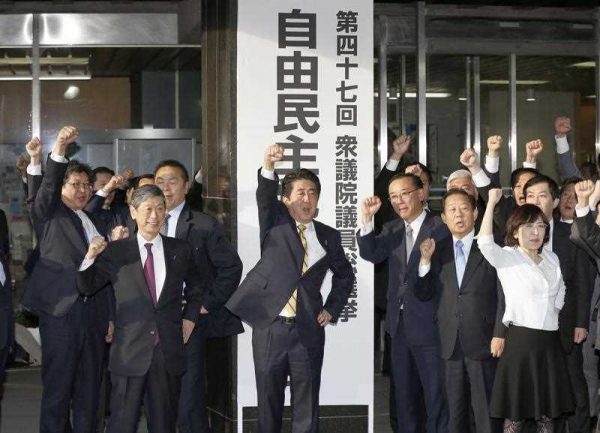

Despite Abe publicly contemplating the possible loss of a coalition majority, this outcome is unlikely. In fact, given the state of the opposition, it is by no means impossible that the coalition will increase the number of lower house seats it has. The conventional thinking is that Abe going to the polls and surviving with a solid majority intact will consolidate his position within the LDP. It will give Abe two more years to implement his difficult policy agenda and the third arrow of Abenomics.

Holding an election will also allow Abe to inaugurate a new cabinet without having to publicly admit that he chose badly in the September reshuffle. The election should also put to rest the pursuit of the money and politics scandals through what analyst Jun Okumura calls misogi or ‘cleansing’. If Abe is skilful, he might be able to remove potential troublemakers in the cabinet such as Shigeru Ishiba and Taro Aso. If he is lucky, some of his critics who are in favour of fiscal austerity might fare badly in their SMDs and not make it back into parliament.

But unless Abe and the coalition win big, two major factors will complicate the implementation of Abe’s policy agenda post-election.

First, all of the major institutional and political veto points will still remain after the election. New Komeito will still be in the coalition and may even be in a stronger position post-election. The dissolution of Your Party, the weakening of the Japan Innovation Party, and the likely end of Shintaro Ishihara’s Next Generation Party mean fewer options for Abe to cudgel New Komeito into submission by threatening to break up the coalition in favour of a more conservative partner. And if the coalition does approach the 270 seat low-water mark, it will effectively make New Komeito the casting vote in both the lower and upper houses. Losses of this magnitude are not likely to be good news for the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) or agricultural reform.

The LDP is unlikely to lose its rural SMD seats, but it is quite likely that the LDP will lose a significant number of urban SMD seats. In such a case, the more seats the LDP loses, the more power LDP parliamentarians from rural SMDs will have to undermine the reform agenda. This will make it even more likely that Abe will have to engage in a public showdown with these entrenched interests to implement his agenda — something which Abe has steadfastly avoided so far. As noted by Tobias Harris, bureaucratic resistance to the monetary and fiscal policies of Abenomics will also remain in place. Unless current economic trends are reversed, fiscal hawks in the Ministry of Finance and the LDP will be well positioned to challenge Abe’s management of the economy and government finances.

Second, while the Japanese public is not likely to repudiate Abe at this point in time, it is unlikely that Abe’s esteem among the public will be improved by going through an election. There has already been significant criticism of the transparently self-serving reasons that Abe called the election. The public does not buy Abe’s excuse of needing to go to the people to get a mandate for delaying the consumption tax for 18 months.

Despite wanting to make the election about Abenomics, Abe will be criticised over a wide variety of issues and he may look increasingly less in control. Due to the absence of a coherent alternative to LDP rule, the opposition attacks will likely not benefit themselves all that much electorally. But nothing short of improved economic news and signs that Abenomics is reviving real wages for the general public will improve Abe’s falling approval ratings.

During the critical first half of the year subsequent to the election, controversial issues that have already been put off will resurface. These include the security legislation connected to collective self-defence, base relocation issues brought up by the recent Okinawa elections, and the TPP and structural reforms. Abe might find that the nine months until the LDP election for the party president is a very long time indeed.

Corey Wallace is a visiting fellow at the Australia–Japan Research Centre at the Crawford School of Public Policy, ANU.