There is rising interest in religion among right-wing politicians in Japan. A number of cabinet ministers are involved in the Association of Diet Members for Worshipping at Yasukuni Shrine Together, a group that aims to promote official political visits to Yasukuni Shrine. Abe, himself a member of the group, controversially made a visit to the shrine on 26 December 2013. Since then Abe has so far refrained from visiting Yasukuni Shrine, sending only a ritual offering on 15 August.

But the connections between the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) and religious nationalism do not end at Yasukuni Shrine.

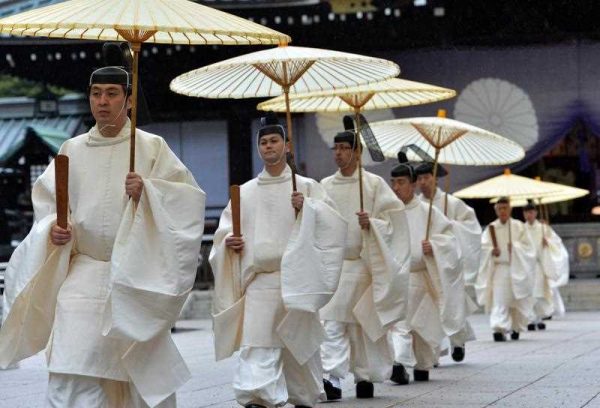

A number of cabinet ministers are also members of the Shinto Association of Spiritual Leadership (Shinseiren). Shinseiren, established in 1969, aims to counter the materialistic nature of modern Japan with a return to traditional Japanese values, focusing on reverence for the Emperor and for the spirits of those who have died for the nation.

The organisation counts a total of 296 Diet members among its supporters, including 16 of the 19 current cabinet members. These include the minister of foreign affairs, Fumio Kishida, and the defence minister, Akinori Eto, as well as Abe himself, who is currently chairman of the Shinseiren group in the Diet. The Shinseiren homepage also has direct links to the political websites of two of Abe’s most recently appointed ministers, Eriko Yamatani, a proponent of patriotic education, and Haruko Arimura. Arimura became widely known after a lecture in January where she claimed that when in doubt about government policy, she visits Yasukuni to ask the heroic spirits for guidance.

A majority of cabinet ministers are also members of Nippon Kaigi (also known as Japan Conference). Formed in 1997, Nippon Kaigi is a self-proclaimed grassroots movement that aims to promote the ‘national spirit’ of Japan. Although Nippon Kaigi is most infamous for its historical revisionism and its push for constitutional reform, their discourses on ‘beautiful tradition’ and the imperial family also contain religious elements.

Organisations such as Nippon Kaigi and Shinseiren — along with the well-known Izokukai (the Japan War-Bereaved Families Association) — are pushing for the revival of a form of Shinto that is similar to the State Shinto of pre-war Japan. Created during the Meiji Restoration to act as the ‘national ideology’ of modern Japan, State Shinto was excluded from the discourse on religion. Instead, State Shinto was to act as a locus of national identity — obligatory for everyone, regardless of personal faith.

When the LDP presented their latest draft for a new constitution in 2012, much attention was paid to the LDP’s attempts to revise the Article 9 ‘peace clause’ and Article 96 (which determines the legal procedure for amending the Constitution), as well as to the Abe administration’s rejection of universal human rights. Not so widely discussed were the implications for religious freedom in Japan.

Articles 20 and 89 of the draft constitution reveal the influence of Nippon Kaigi and Shinseiren ideology on LDP policy. While Article 20 says that the state is not allowed to favour any particular religious organisation, this restriction does not apply to ‘folk customs’ or ‘social courtesy’. Article 89 keeps the limit on public funding of religious organisations, but only as defined by Article 20. What this means is that the state is free to, once again, define Shinto as a ‘non-religion’, thereby eluding any constitutional restrictions on state affiliation with religious organisations.

The growing influence of religious-nationalist interest groups, and their promotion of State Shinto, is increasingly reflected in the actions and policies of the Abe cabinet. Abe’s visit to Yasukuni Shrine, along with his repeated visits to Ise Shrine, indicates a strong support for religious symbolism. Abe is currently balancing the interests of the LDP’s far-right supporters against the need to uphold normal diplomatic relations with Japan’s neighbours in East Asia. But given increasing LDP ties to groups such as Nippon Kaigi and Shinseiren, Abe will eventually have to pick a side.

Former Japanese prime minister Junchiro Koizumi’s insistence on visiting Yasukuni Shrine every year during his term considerably worsened diplomatic relations with South Korea and China. Koizumi did this mainly to placate the Izokukai. Abe’s involvement with right-wing groups runs much deeper than that of his predecessor and, while he chose not to visit the shrine during his first term as prime minister in 2007, it remains to be seen whether he can abstain from making a 15 August visit throughout his soon to be renewed term.

Under the present Abe cabinet, religious nationalism has gone from being a peripheral phenomenon in Japanese politics to having a place at the centre of LDP policymaking. The religious right is gaining influence in the Diet and the issue of constitutional reform has still not been settled.

What remains to be seen is to what extent the Japanese electorate is willing to support what has been described as a ‘Tea Party of Japan’. The LDP came to power through a lack of serious opposition from the Democratic Party and a general hope that Abenomics can restore the Japanese economy, not through any clear support of their nationalist policies. The influence of Japan’s religious right could have serious ramifications for the individual rights of Japanese citizens, as well as for diplomatic relations in East Asia.

Ernils Larsson is a PhD candidate in the History of Religions at the Faculty of Theology, Uppsala University.