But, since 2012 China has been taking a more assertive stance towards territorial disputes in the South China Sea — raising significant policy questions for the United States.

China has controlled all of the Paracel Islands since 1974 when it forcefully ejected South Vietnamese forces. Despite Vietnam’s continuing claim to sovereignty, China is unlikely to ever leave. China also effectively resolved the dispute with the Philippines over Scarborough Shoal in 2012 when it established control over the shoal. Again, it is unlikely to relinquish it. This means that the Spratly Islands (with overlapping claims from China, Taiwan, Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia and Brunei) are the only remaining disputed area in the South China Sea not completely under the physical control of China.

Washington takes no position on sovereignty disputes in the South China Sea, but it does oppose states engaging in destabilising behaviour in pursuit of sovereignty claims.

The current US policy towards the South China Sea rests on the most important US interest — freedom of navigation. US policy exhorts all parties to follow the rules of international law as the surest way to achieve stability. It also explicitly defines how Washington would like conflicts to be solved (through peaceful negotiations) and includes hard-power initiatives aimed at redressing some of the power imbalances between the Philippines, Vietnam and China. US policy further incorporates an element of deterrence by not ignoring America’s security alliance with the Philippines as well as providing access for US naval and air forces in Singapore and the Philippines.

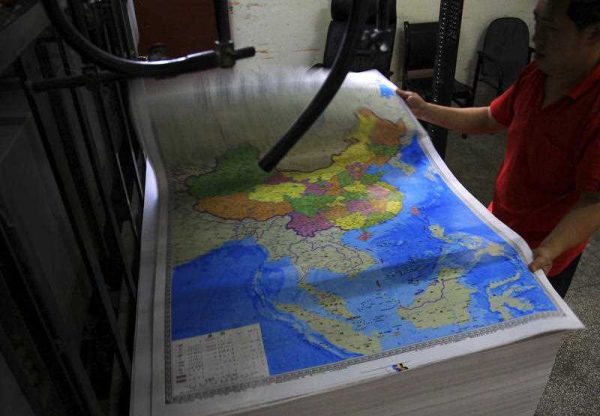

Washington’s public rhetoric has, over time, become far more specific and less diplomatic. It now specifically calls China’s actions destabilising and bullying. The US has also become more specific in its commentary regarding the rules governing sovereignty disputes. The US has especially criticised the most destabilising aspect of the disputes in the South China Sea: China’s nine-dash line.

Unfortunately, China has largely ignored US exhortations to follow the rules, to stop pushing other claimants around and to seek third-party arbitration to resolve claims. Beijing apparently believes that national interest trumps adherence to international law.

So what should the US do?

I argue that South China Sea policy should not be overwhelmingly anti-Chinese. The United States should criticise Chinese behaviour, along with the behaviour of American friends and allies, when it is warranted. When it comes to the South China Sea, Washington should not announce policies it is not prepared to back up.

The United States should issue a comprehensive white paper on the various aspects of international law that are being abused by China and other claimants in the South China Sea.

US officials have publicly supported a request for arbitration from the Philippines that, among other things, seeks to clarify whether China can make a maritime claim based on the nine-dash line. But the tribunal could rule that it does not have jurisdiction. That would be a major setback to hopes that international law can be the basis for shaping the behaviour of parties involved in South China Sea disputes. The US Department of State should publicly highlight the importance of allowing the Philippines to have its day in court.

The US should also help South Sea littoral states help themselves through improvements in surveillance, command and control, and policing of their respective maritime domains. The United States also needs to be completely committed to a very long-term and dedicated effort to improve the maritime capabilities of the Armed Forces of the Philippines. Both sides need to mutually agree upon a ‘minimum credible deterrence’ plan.

US naval and air presence in the South China Sea should be a visible daily occurrence. To that end, the US should increase the duration of its exercises with South China Sea littoral states and expand participation in these exercises by inviting participation from other Asian maritime states, such as Japan, Australia, South Korea and possibly India. This will increase US presence in the region and illustrate that other maritime states are concerned about stability in the South China Sea.

Finally, Washington should ensure that planned US military posture and capability improvements in East Asia are portrayed as symbols of reassurance and stability and are not characterised as attempts to directly confront China. The US must emphasise that the objective of the military portion of the administration’s rebalance strategy is to ensure that the United States can fulfil its security responsibilities to its allies and friends.

Admiral Michael McDevitt is a senior fellow in Strategic Studies at the CNA Corporation. A more extended version of the author’s argument is presented in a recent CNA Occasional Paper.

There are a couple of interesting issues you raise. First, you say “when it comes to the South China Sea, Washington should not announce policies it is not prepared to back up.” Then later you mention that ” the US should also help South Sea littoral states help themselves through improvements in surveillance, command and control, and policing of their respective maritime domains…..(The Philippines and the U.S.) need to mutually agree upon a ‘minimum credible deterrence’ plan.”

What does deterrence include? Or, more specifically, how far are you willing to go to deter China? As is known, they are aggressive in protecting what they think are their legitimate claims. At the sake of ‘being prepared to back it up’ are you ready to put U.S. ships in disputed territory in order to patrol the area? How long would we commit our ships? What happens if there is an engagement? You think China will forget about their claim once we leave?

I am afraid China can be aggressive because they know they can. Just like no one is going to force Russia to give back Crimea, no one is going to physically force China to give back the Spratley Islands. And besides, it’s really not the islands themselves that are important (even with its oil), but the future potential for China to disrupt trade routes, as you mention in your article. It would therefore be open and free navigation in the South China Sea that would serve as a trip wire, but not the Spratley themselves.

So what’s left? International justice? Well, my impression of China is that their foreign policy is not based on having friends, and it’s not based on avoiding enemies- their foreign policy is based upon interests, and interests alone. Therefore, if it is not in their best interests to have a Western-based International Court of Law decide their fate for them, they will ignore it. The only way they respond to an issue is when they feel it overlaps into an area of greater concern for them.

Therefore, linking a desired outcome with other areas which China deems of greater importance is the strategy that the U.S. should take. It will be difficult, as China can gain support by pushing a lot of economic weight around. But I am afraid that this problem, and others similar to it, won’t be resolved in a way that is satisfactory to the U.S. unless we stop thinking tactically and begin thinking systematically.

Many of the points you raised regarding China’s ability to change the facts “on the ground” are addressed in detail in my longer report. China has economic, geographic and political leverage over the other SCS claimants; that is why it has been so difficult for Washington and ASEAN to convince Beijing to resolve the dispute diplomatically.

Also we cannot loose sight of the fact that China really does believe they have the best legal claim to sovereignty. When you look at a range of credible experts (not Chinese) who have tried to untangle the sovereignty issue, you have a mixed verdict–some say Vietnam, others say China, and at least one says Taiwan, have the best claim to the Spratlys.

By the way you mentioned China being forced to give back the Spratly’s–there is nothing to give back since they only control 7-8 features in the Spratly chain. Vietnam is far and away the largest “landholder” and I suspect Hanoi would fight if China tried to forcibly evict them.

In terms of Washington’s approach, it is essential that Washington keep the SCS in perspective, US policy and actions need to be weighed within the context of the overall relationship. The SCS is not at the center of the Sino-US universe.

On the issue of deterrence, my main argument is that US SCS policy does include an element of deterrence, because the US-Phil MDT does include language that could involve the US directly with China if the Chinese shoot up a Philippine public vessel or aircraft or kill Philippine servicemen. During the Obama visit to Manila earlier this year he emphasized the continued relevance of the treaty relationship between Manila and Washington–this was not by accident.

With regard to my comment about helping the Philippine’s create a “minimum credible deterrent.” That is the what the Philippine’s have named their military modernization plan. I don’t know precisely what they have in mind in terms of capabilities, that is why I indicate the details of the plan should be mutually agreed upon between Washington and Manila. I don’t support the US blindly agreeing to a military modernization plan unilaterally developed by Manila.

Finally, I am not entirely sure what you mean by thinking systematically. Although my report suggest things Washington should do to advance US interests, in general terms I would give the Washington good marks on strategic thinking. While it is too soon to say for certain, Beijing’s apparent softening in terms of its SCS approach, if not its objectives, suggest that the efforts of Washington ASEAN, or least the ASEAN SCS “frontline states,” has contributed to this apparent change in Beijing’s policy approach.

An even more symbolic expression of US redirection in the South China Sea is a public apology to Vietnam for helping PRC initiated expansionist territorial aggressions with the invasion of Paracel (1974 – 7th Fleet permission for attack against US ally, war partner: South Vietnam)and again the deadly occupation of 6 Spratly rocks which are now Chinese sand reclamation (1988- the US led international sanction against the unified Vietnam). Had the US not conspired with its newly acquired strategic partner PRC (1973) and sacrificed Vietnam’s territorial integrity in the process: Chinese forces projecting out of its southern most point of Hainan would be of no military consequence, today.

Cathy, you are not correct; there was no US permission to allow China to attack the Paracel’s. Cite a source to back up your claim but there is none. Nixon was at the end of Watergate and had less than 7 months left in office. The Democratic congress was looking to finish up in Vietnam and was willing to surrender.

If you are looking for a telegraph from the PRC to Nixon and/or a recorded voice of Chinese Navy commander to the 7th fleet officer then, I don’t. But, here are what constituted a “permission”:

Recently, declassified materials of a 1973 Kissinger direct reply to Chinese that the US forces will not intervene in the SCS conflict between S. Vietnam and China. That constitutes a permission!

Yes, the US military engagement in Vietnam was winding down but how did the Chinese fleet of 12 warships and 2 dozens large fishing ships filled with soldiers in civilian clothes, traveling over 3 days to Paracel without being detected by the 7th Fleet? Of course, they were detected but S. Vietnam was not warned at all. That constitutes a permission!

Three days after the 2 damaged Vietnamese ships made to shore, surveillance was done to identify enemy positions with minimal anti-aircraft capability and 62 S. Vietnamese fighter jets assembled in DaNang for a counter-attack. The US ambassador told president Thieu to scrap such plan. That constitutes a permission.

PRC’s final plan to invade Paracel was approved in Sept. 1973, 3 months after the Kissinger conversation and neither the Chinese, the Vietnamese nor any American had a clue that Nixon would resign in Aug 1974.

Cathy I looked on the internet and could find no source to back up your claims. Cite a source that can be checked. China had 6 ships not 12. With Watergate and the Mideast war just ended and the 400% increase in the price of oil, Washington may have had more on its mind then some uninhabited island off Vietnam. But I am always ready to believe the worst about Kissinger.