While the CCP was established in 1921 (and came to power in 1949), the Catholic Church has maintained a presence in China for far longer. Nestorian Catholics were around in the eighth century and Catholic missions were established in the sixteenth century. The history of Catholicism in China offers important perspectives on the church as a global organisation and the religious landscape in China.

China is the one country where the Vatican does not influence the training and selection of clergy. The Vatican formalised reciprocal relations with the government of China in 1946, three years after a Chinese legation was established at the Holy See.

But the tumult of the Chinese Civil War and the rise to power of the CCP had lasting repercussions for the church.

Between January 1951 and May 1954, 3038 Catholic missionaries left China. Many went to Taiwan, the former Japanese colony where the Kuomintang (Chinese Nationalist Party) was attempting to assert itself domestically and internationally as the legitimate government of ‘China’. Taiwan maintained ties with the Vatican. Subsequently, there was spectacular growth in the number of Catholics in Taiwan, rising from 8000 in 1945 to over 181,000 in 1960. Catholic social services, such as healthcare and education, are now features of society in Taiwan.

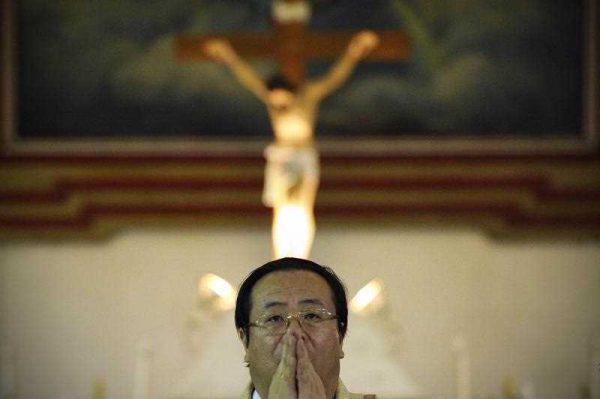

In July 1957 the CCP, an officially secular and atheist organisation, established its own Catholic church — the Chinese Patriotic Catholic Association. This organisation maintains authority over the church in China.

Even with the CCP’s endless efforts to control religion in China, those who want to practice Catholicism (or any other religion for that matter) are still able to do so. Catholic house churches exist, allowing Catholics to discretely worship outside of the CCP’s direct sphere of influence. These clandestine practices make accurately counting the number of Catholics difficult. There could be as many as 12 million Catholics in China, although estimates vary.

Despite Pope Francis’ friendly overtures to Xi, reconciliation is nothing more than a pipedream. Xi is exercising authority in a way his predecessors had not done for some time. The ongoing ‘yellow-umbrella’ occupy movement in Hong Kong is evidence of how one part of China is reacting to the political realities of his rule.

Among the voices advocating greater autonomy for the citizens of Hong Kong is the former head of the Catholic Church there, Cardinal Joseph Zen. In contrast to the official Church, which has urged restraint, Cardinal Zen framed the quest for democracy as ‘a question of the whole culture, the whole way of living, in this our city’. Such a forceful repudiation of state authority would upset the CCP, which does not have a strong record of engaging with dissenting views.

For all the social services that the Catholic Church could bring to China, it is difficult to imagine the CCP tolerating an organisation that potentially harbours such outspoken individuals. Nor would it want to see the number of Catholics increase, as happened in Taiwan. That said, Catholicism will surely survive in China in one form or another.

The Catholic Church has a history far longer than that of the CCP and a much more extensive global reach. Just as Xi is acutely aware of the power of history in helping to legitimise the CCP, he must also be aware of the Catholic Church’s lengthy past. The church may not be able to enter China officially under Xi, or even a later CCP leader, but it likely will again at some stage in the future.

Paul Farrelly is a PhD candidate at the Australian Centre on China in the World, the Australian National University.