While this might not come as a huge surprise — given that recent months have seen several high-level exchanges between Japan and South Korea — Park had steadfastly declined to meet with Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe since both leaders took office. The annual China–Japan–South Korea trilateral summit was last held in 2012, as relations among the three countries deteriorated.

Issues clouding relations among the three Northeast Asian countries include maritime territorial disputes — China and Japan dispute the sovereignty of the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands, while Japan and South Korea dispute the sovereignty of the Dokdo/Takeshima Islands — and historical legacies arising from World War II. In particular, South Korea and China want Japanese leaders to show remorse over the ‘comfort women’ issue and to stop visiting the Yasukuni Shrine, which is viewed as a reminder of Japan’s past militarism. Given that none of the three countries have changed their positions on these issues, why is Park now willing to meet with Abe within the framework of the trilateral summit?

Proverbially referred to as a ‘shrimp among whales’, South Korea is vulnerable to fluctuations in major power dynamics. In fact, the Korean peninsula is where the interests of global and regional powers — the United States, China, Japan and Russia — intersect. Yet, being a relatively weaker power, South Korea is unable to unilaterally influence global and regional agendas.

To secure its interests, South Korea has turned to middle power diplomacy, which is typically characterised by a commitment to multilateralism, conflict mediation and international activism. Being less materially powerful, middle powers rely on soft power and network building to carve out a significant role for themselves in world affairs. Park’s proposal is thus likely driven by one concern, which is to avoid diplomatic isolation. This is a looming possibility as other bilateral relations in Northeast Asia seem to be on the mend.

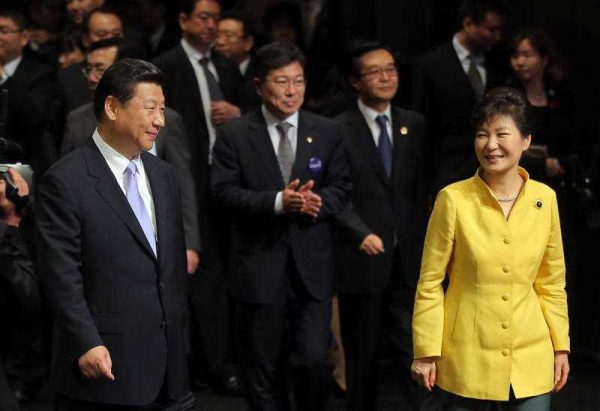

Three days before Park’s proposal of a three-way summit, Abe and China’s President Xi Jinping held a 25-minute meeting on the sidelines of the APEC summit in November. The Abe–Xi meeting followed an agreement to resume political, security and diplomatic dialogue. Sino–Japanese relations have spiralled downwards since the collision between a Chinese fishing trawler and two Japanese Coast Guard patrol boats in September 2010. Japan’s nationalisation of three of the disputed Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands in 2012 worsened already tenuous bilateral ties. Xi and Abe had not held a meeting since they each took office in 2012.

While the Xi-Abe meeting at the APEC summit does not indicate a resolution of the underlying issues plaguing Sino-Japanese ties, it is nevertheless a symbolic achievement. Both sides have reiterated the importance of the bilateral relationship, and agreed to establish a maritime crisis management mechanism. Should relations between the two Northeast Asian countries improve, South Korea, as the non-major power, could be relegated to the back seat in regional dynamics.

Another Northeast Asian bilateral relationship that has shown signs of thawing is that between Japan and North Korea. Anti-Japanese sentiment in North Korea stems from the former’s past colonial rule over the Korean peninsula. In Japan, hostility toward North Korea arises from the latter’s abduction of Japanese citizens in the 1970s and 1980s, as well as the nuclear and missile threat posed by the secretive regime.

This year, however, Tokyo and Pyongyang have resumed talks on the abduction issue, which had been stalled for a decade. No significant breakthrough has been made so far, but Japan has lifted some economic sanctions on Pyongyang and dangled the promise of humanitarian aid. While still very limited in nature, this development is significant because it suggests that a united US–Japan–South Korea strategy to deal with North Korea could potentially be undermined and South Korea’s interests on the issue sidelined.

Admittedly, recent developments in Sino–Japan and Japan–North Korean relations might not bear fruit. After all, tensions among these countries are longstanding and arise from deep-seated historical issues that seem unlikely to be resolved anytime soon. Yet, considering the possibility of improving Sino–Japanese relations on the one hand and thawing Japan-North Korean relations on the other, South Korea could increasingly find itself diplomatically isolated from its neighbours. Park’s timely proposal of resuming the trilateral summit, therefore, could be a step to prevent that scenario from coming to pass.

With the Trilateral Cooperation Secretariat based in Seoul and South Korea as the current chair of the trilateral summit, Park’s proposal reminds her neighbours that South Korea could assume an important role in Northeast Asia even if it is a non-major power. At the same time, the resumption of the trilateral summit would contribute to the realisation of Park’s Northeast Asia Peace and Cooperation Initiative (NAPCI), which calls for establishing regional peace and stability through multilateral cooperation and trust.

South Korea has since the late 1990s identified itself as a middle power. In the current climate, Seoul-led progress on the trilateral summit and the NAPCI would help to further cement South Korea’s status as a middle power in regional affairs.

Sarah Teo is an Associate Research Fellow with the Multilateralism and Regionalism Programme, S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Nanyang Technological University.