China now has a new ideology: Xiism. Xi’s power could be seen through the control over Party messaging, which Xi stood at the centre of. From the development of the China Dream theme which first appeared at the end of 2013, to the New Silk Road concept which seemed to embrace most of the world, Xi was the central spokesperson. This culminated by the end of the year with a bulky book carrying Maoist-style pictures of Xi on the front and inside grandly titled ‘On Governing China’.

Xi’s power could also be seen in a more brutally political way in the ongoing anti-corruption campaign, which finally reached the door of former Politburo Standing Committee member, Zhou Yongkang, who was formally expelled from the Party and indicted for ‘corruption and fornication’ in November 2014. Zhou’s treatment is unprecedented in modern China, and showed Xi was willing to take on powerful vested interests and deal with the consequences.

There was no sign throughout 2014 that Xi was insecure in his position. Public approval of the corruption campaign was high, leading to a whole new mode of behaviour by officials. And the Fourth Plenum held in October 2014 produced a lengthy disquisition on strengthening ‘rule of law with socialist characteristics’ which also appealed to the newly emerging, all-important Chinese middle class with their interest in stronger property rights, a more predictable legal environment and a sense that the government was listening to them.

All of this tended to put Xi’s colleague, Premier Li Keqiang, somewhat in the shade, despite him ostensibly being in charge of macroeconomic issues. Li visited the UK, India and other countries during the year, but his profile was low. It seems that the real manager of China’s slowing economy was Liu He, who Xi made clear was one of his most trusted advisors, and who heads the small group on the economy.

Both Xi and Li however remained consistent on one issue, and that was that China’s growth rate is now set at below 7.5 per cent and the Chinese people have to live in a world where double-digit GDP growth is a thing of the past. The main focus now is on creating an economy that is service sector orientated, that consumes more, that is more urban, and that is less driven by investment than previously.

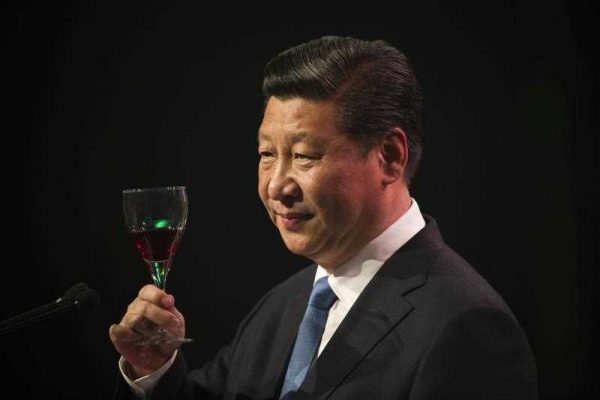

Xi spearheaded a diplomatic offensive, visiting countries in Latin America, Africa, South Asia and then, in November, attending the G20 summit in Brisbane, visiting Canberra and travelling to New Zealand and Fiji. In Brussels in late March he articulated the concept of the EU and China being ‘civilisational partners’. But he also managed to come up with the New Silk Road mantra, which covered a land and maritime link. And he embraced a Russia ostracised by Europe and America over its actions in the Ukraine, and a Middle East where China was rapidly becoming one of the key players, despite efforts to keep out of the treacherous politics there.

Even with the US, Xi was able to produce a surprise during the APEC meeting in early November by signing off a major environment protocol with his American counterpart. He also announced with Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott final details of a Free Trade Agreement, and supported an Asia-wide free trade zone concept, the FTAAP, putting him in conflict with the United States and the Trans-Pacific Partnership process it is driving.

This hyperactivity betrayed a China which no longer wished to be as isolated as it had looked in the later Hu and Wen period up to 2012. A tepid rapprochement was made with Japan in November.

After its initial support for the Hong Kong government’s proposals for how elections for the Chief Executive in 2017 might be run, it largely kept out of direct dealings with the subsequent protests in the city. On Taiwan, too, Xi continued to be a mixture of pushy (demanding more consideration of the ‘one country, two systems’ idea, precisely at the time it seemed to be falling apart in Hong Kong) and supportive of incumbent President Ma Jing-jeou, despite the latter’s disastrous mid-term election results in November.

Ironically, perhaps the one area where Xi seemed to be bereft of new ideas was North Korea, which he dealt with largely by ignoring it, even when its young leader mysteriously disappeared for a number of weeks in September.

For all the energy and determination of the Xi leadership, there was one area where it remained utterly consistent with its predecessors: human rights lawyers and dissidents were ruthlessly dealt with. IIlham Tohti, a Beijing-based Uighur academic received a life sentence. Academics, intellectuals and people from the artistic sphere were given strict instructions on what was regarded as healthy, and what was proscribed.

There seemed to be few things that China’s new but confident leader did not feel qualified to opine on, even daring to issue instructions to the much derided national football team on how to play better. This, in hindsight, may well be the bravest statement he made all year. With almost all other areas, as one commentator stated, there was hope, but for Chinese football ability despair and disappointment was the default, and that alone looked unlikely to change, despite Xi’s brave intervention.

Professor Kerry Brown is Executive Director of the China Studies Centre at the University of Sydney.