The placement of China’s oil rig in Vietnam’s claimed exclusive economic zone and the tense vessel confrontation between the two coast guards for almost ten weeks not only sparked large anti-China protests throughout Vietnam but also precipitated a heated internal discussion on the need to rethink Vietnam’s China policy — how to escape China’s orbit.

At the height of the crisis, some of the most radical elements within the Vietnamese intelligentsia suggested that the country should build strategic allies with the US and its partners as a counter-measure against China’s possible territorial encroachment.

Shortly after the crisis, Japan announced that it would provide Vietnam six patrol vessels, funded by foreign aid. On 2 October, the US partially lifted its lethal arms sales, paving the way for Hanoi to purchase high-end equipments to enhance its maritime capacity. On 28 October, India also announced that it would sell $100 million worth of naval and patrol vessels to Vietnam in exchange for energy exploration rights.

Clearly, Vietnam’s strategic role has become more salient in the US Asian pivot, Japan’s Look South strategy, and India’s Act East policies. This, in turn, facilitates Hanoi’s goal of internalising the disputes so as to restraint China’s unilateral actions. The downside of this, however, is that Hanoi risks becoming a proxy for other powers to contain China’s assertiveness in maritime disputes.

Hanoi’s strategy thus far has been moderate: seeking to mend fences with China and reiterating its long standing ‘three nos’ defence policy (no foreign bases in Vietnamese territory, no military alliances, and no relationships against a third party) while strengthening ties with other powers.

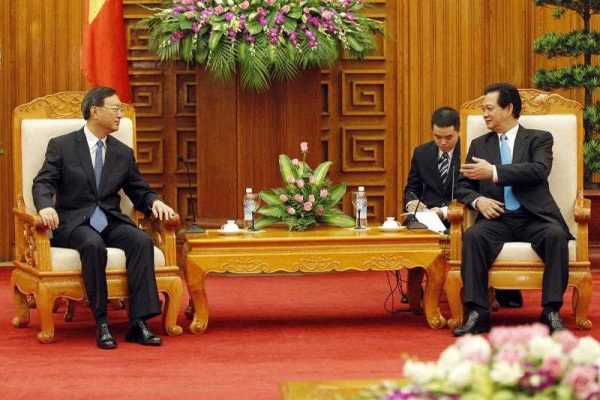

Why? First and foremost, this nuanced reaction reflects the historical roots of Vietnam’s strategic thinking, one that views a workable relationship with China as vital to ensure Vietnam’s stability and security. Following the removal of the oil rig on 15 July, Hanoi has sent two high-ranking delegations to China (by Politburo member Le Hong Anh in August and Defence Minister Phung Quang Thanh in October) during which the two sides agreed to repair ties and to establish a military hotline to forestall incidents like the oil-rig dispute in the future.

Second, the management of the oil rig crisis, from a Vietnamese perspective, was a success. The two factors that have contributed to the peaceful resolution of the tensions, as Foreign Minister Pham Binh Minh outlined, are Vietnam’s experience in dealing with China and the support received from the international community. Minh further argues that, ‘other countries, for example the Philippines may not predict [China’s behaviour] but we do, we know China.’

Third, economic benefits matter. While recently pursuing an ‘economic pivot’ to Japan with a focus on investment and the US with a focus on exports and the TPP, Vietnam still immensely relies on Chinese imports. Despite the rhetoric of ‘escaping China’s orbit’, Vietnam’s trade deficit with China is expected to hit a new record of US$27 billion in 2014. Hanoi also cannot ignore the ‘carrots’ Beijing is offering, including the ‘Maritime Silk Road’ and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) initiatives.

Arguably, the logic of ‘if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it’ applies in Vietnam’s strategic thinking with respect to China. Yet Hanoi may find it increasingly difficult to maintain this approach should China continue crossing red lines. On 11 December, Vietnam joined the Philippines and the US in rejecting China’s nine-dash line in the SCS in its statement of interests submitted to the Court in the Hague that is handling the Philippines-China case. If anything, this action has ushered in a shift towards a bolder approach in Hanoi’s stance.

With all this in mind, 2015 promises to be a year of important tasks for Vietnamese diplomacy. On 30 April, the country will celebrate the 40th anniversary of the end of the Vietnam War. National reconciliation is expected to be high on the agenda of Hanoi’s policy towards the large overseas Vietnamese community. Nationalism and tensions may arise, however, when it comes to sensitive issues such as ‘political dissidents’ and the SCS disputes with China.

It will also have been two decades since Hanoi’s historic triple decisions to deepen its integration into the international community: it joined ASEAN, normalised relations with the US, and concluded the Framework Agreement with the EU. Diplomatic negotiations are currently undertaking to prepare for high-ranking visits to celebrate the 20th anniversary of the normalization of Vietnam–US relations. There are chances that Hanoi and Washington may decide to lift their current ‘comprehensive partnership’ framework to a ‘strategic partnership’ level in the year. Nonetheless, much of this progress will depend on how the two countries settle their differences over human rights issue.

Last but not least, 2015 will be an important transitional year towards the 12th Party Congress. Almost 30 years after the Doi Moi reforms of 1986, it is now time for the Party to review the lessons of that period so that better economic policies can be devised to help the country escape the ‘middle-income trap’. In a speech at the Asia Society in New York on 24 September 2014, Foreign Minister Pham Binh Minh stated that in order to secure a favourable place in the evolving world order, Vietnam needs to deepen economic reforms, to further its open and self-reliant foreign policy, to act as a responsible player in the world affairs, and to promote an ASEAN-led regional order. It is on these crucial points that Vietnam should reposition itself better.

Thuy T Do is a PhD candidate at the Department of International Relations, The Australian National University and a lecturer at the Diplomatic Academy of Vietnam.

This article is part of an EAF special feature series on 2014 in review and the year ahead.

Nice job!

This opinion piece is surprisingly more balanced than the title would indicate. I had feared that it would be yet another nationalistic screed by biased Vietnamese bloggers and so-called scholars. Those pieces do not fool nor impress objective analysts, do a disservice to the reputation of Vietnamese academics, give false hope to the Vietnamese public and mislead policy makers. This piece, while not as egregious as its title, nevertheless misses the forest for the trees.

Vietnam’s foreign policy in 2014 regarding the South China Sea was disastrous. It resulted in the worst tension with China since their 1988 violent clash in the Spratlys. The confrontation over China’s oil rig provided a clearly unforeseen opportunity for anti–China (and anti-Chinese) Vietnamese to vent –which in turn precipitated murderous anti-Chinese riots in Vietnam. It also intensified the split between pro and anti-China factions in the leadership. Worse, it stimulated renewed anti-Vietnam antipathy and distrust of Vietnam in China generally and in its leadership as well as stepped up strategic thinking regarding the possibility of Vietnam becoming a US pawn in the US-China rivalry for dominance in the region. Vietnam’s pandering to the U.S., its recent mortal enemy that has yet to fully atone for what many consider its racially motivated atrocities during the war, was disingenuous, distasteful and unworthy. It demonstrated a lack of understanding of US strategy for the region as well as disrespect for the millions of Vietnamese who suffered and died to reject and eject US ideological and political influence. Further, Vietnam’s public support of the Philippines and its lobbying for support and sympathy for its actions within ASEAN enhanced stresses and disunity within the organization –just when it needed the opposite.

There is no way to sugarcoat it. Vietnam’s decisions and actions in 2014 regarding the South China Sea may be viewed as a short-term success by short-sighted analysts but they may well be a long -term disaster for Vietnam’s China –relations and internal stability. Vietnam—and analysts of its foreign policy need to remove their nationalistic blinders , be realistic and think more long term and inn the interest of ASEAN if it is to avoid becoming yet again a pawn in a great power rivalry.

Only uncritical acceptance of Beijing’s nine dash line, a strained interpretation of Law of the Sea principles and belief in China’s mostly fictitious historical claim to the features of the South China Sea can explain Mark Valencia’s comment above. Dr. Valencia would have readers believe that Vietnam provoked China by protesting Beijing’s deployment of a deepsea oil drilling rig within Vietnam’s EEZ. Valencia’s suggestion that Hanoi’s strategic rapprochement with Washington is naive, that it somehow dishonors Vietnamese who sacrificed to secure the country’s reunification half a century ago, is disingenuous and distasteful. Yes, Dr. Valencia, submission by Vietnam and its ASEAN neighbors to China’s pursuit of hegemony in the South China Sea region may indeed lead to a sort of stability, but it will be much like the ‘stability’ that the Soviet Union imposed on Eastern Europe after World War II.