The Chinese government is claiming that the reforms in the Shanghai FTZ are moving solidly towards their targets. But suspicions are still prevalent. It usually takes quite a long time before practical reform takes effect. And announced measures seem far below what was initially proposed in the blueprint. There are real concerns as to whether China’s government can really achieve its goals. Can China really overcome the anti-reform forces and vested interest groups (which, admittedly, include the bureaucrats themselves)? One year on, how have the reforms of the Shanghai Free Trade Zone (SFTZ) fared? Is the Shanghai Free Trade Zone model one that could be replicated throughout China?

There have been six key dimensions of the Shanghai Free Trade Zone. Government administration has been made more efficient, from the approval system to the filing system. A negative list approach has been adopted on foreign investment. New trading modes have been developed by introducing offshore trading and futures trading, and financial liberalisation has been pursued through interest rate marketisation, exchange rate liberalisation, renminbi internationalisation and relaxing controls on the capital account. Restrictions on the services sector have been relaxed, such as in education (professional training), healthcare, entertainment and tourism. And a transparent and fair legal system has been developed to replace the existing one, committing the government to be competition-neutral.

These are all important reforms and would be beneficial if replicated in other zones throughout China — as long as they are carried out properly.

China’s reform process is a top-down system, a product of the nation’s hierarchical political structure. Senior bureaucrats play a critical role in the reform process. To date, reforms have not been well prepared and the process poorly managed. This is largely a result of insufficient time given to bureaucrats to understand and adjust to the proposed reforms. This understanding at the top is important for the practical implementation of the plans on the ground.

In general there have been two streams of challenges to reform. Both challenges facing reformers call for very different approaches. The first stream is concerned with government itself. It includes aspects such as implementing a filing system and creating competitive neutrality in the market. Here the issue is the capability of the bureaucracy. It requires an aggressive approach, which it has received in the past year.

The other is about market liberalisation. This means creating a negative list and greater financial liberalisation — particularly towards foreign investors. This stream is more prone to risk and has also, aptly, been tackled effectively with a conservative approach.

There are three main factors contributing to China’s economic slowdown. These are the withdrawal of the massive fiscal stimulus of recent years, the urgent need for industrial upgrading due to worsening environmental and demographic pressures, and the need for domestic reform to enable China to participate in high quality free trade and investment agreements. These agreements demand comprehensive openness not only in the area of merchandise goods but also in agriculture, services and finance, as well as legal systems that facilitate foreign entry and operation. Given the current internal and external economic pressure, China should not only get these reforms right, but also do them as soon as possible. But the existing reform process suggests that the current reform process may just hold up.

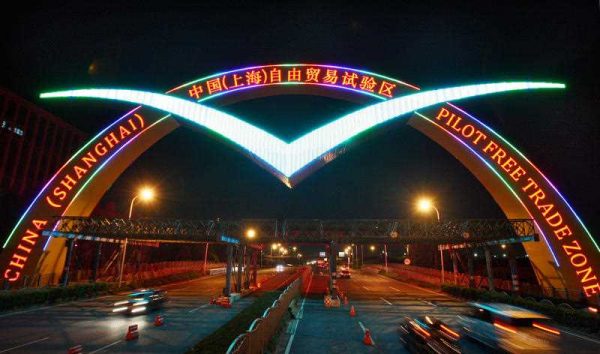

China announced in December 2014 that it would establish another three FTZs in Tianjin, Fujian, and Guangdong. It has been reported that these three new FTZs will implement most of the reform measures put in place in Shanghai FTZ and also devise their own policies relevant to their regional economic features.

Each of the three proposed FTZs has its own unique features. Tianjin specialises in international shipping and related business. Fujian is closely connected with Taiwan. And Guangdong is hoped to copy Hong Kong and Macau in terms of its high-end services (particularly financial services). This is a strategy for accelerating, expanding and replicating the ambitious reforms in Shanghai.

Shanghai, Tianjin, and Guangdong represent the centres of the three most important economic areas in China (that is, the Yangtze River delta, the Bohai rim, and the Pearl River delta). More FTZs will mean more competition for faster and better implementation of the reform agenda — a necessary step towards a stronger economy.

Bo Chen is an Associate Professor and Secretary General of the Research Institute on Shanghai Free Trade Zone, Shanghai University of Finance and Economics.