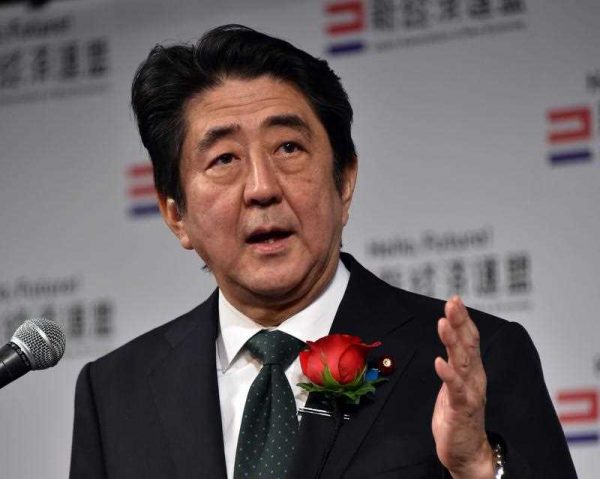

After Abe’s snap election on 14 December 2014, the rising star of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), Shinjiro Koizumi, accurately characterised the election as ‘the election with no enthusiasm, an overwhelming victory with no fanaticism’. Voter turnout was a record low at 52.8 per cent. Voters had no real choice in electing a new government, or in selecting alternative economic policy. The Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) failed to present itself as a responsible, reliable alternative to the LDP. From the beginning, the election was destined to be a vote of confidence in Abe.

The election was a good result for Abe. But it still left a bitter taste. The good news was that the government coalition of the LDP and the Komeito kept its two-thirds majority in the lower house, which means that it will continue to control the Diet. Abe is also the first Japanese prime minister to win two landslide victories in a row since the introduction of electoral law reforms in 1994.

The bad news for Abe was the retreat of the nationalist cluster and the rise of the liberals. The LDP lost four seats, while the Komeito, its more liberal coalition partner, gained four. The LDP will be dependent on the Komeito’s cooperation in 2015 and 2016, when there will be nationwide local elections and an upper house election respectively. Behind the landslide victory of the coalition government, the nationalist Party for Future Generations (Jisedai no to) was almost wiped out. Meanwhile, the Communist Party was the greatest beneficiary, increasing the number of its seats from 8 to 21. The DPJ, despite leader Banri Kaieda losing his seat, also increased its seat count by 11.

Abe’s second term revealed amazing pragmatism in comparison with his first (2006–2007). He adopted two faces: a nationalist one at home (even more so on social networking services) and an internationalist one abroad, and with some success. At home, Abe visited Yasukuni Shrine and showed his unwillingness to compromise with China and South Korea over history issues (although he insisted that the door for dialogue was always open). Abe also introduced the Act on the Protection of Specially Designated Secrets. As an internationalist, Abe 2.0 raised expectations for Japan’s economic recovery on the economic policy front. He met 121 state leaders around the world, a total of 246 times, and visited 50 countries, making various commitments to economic cooperation. He also advocated concluding the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), strengthening the US–Japan alliance, and seeking a greater role in regional security. He impressed upon the world that Japan was back, and that he himself was back. Then, without compromise, Abe eventually met with the leaders of China and South Korea — even though these meetings were more symbolic than substantial.

At the same time, Abe 2.0 was modest, cautiously getting things moving. He avoided contentious issues which would have required him to mobilise extensive political capital. For example, Abe quickly took a fall-back position on the amendment of the Constitution when he realised that it would not garner public support. Instead he moved towards reinterpreting the constitution to allow collective self-defence as a relatively minor change. He was also cautious in handling the restarting of Japan’s nuclear power plants, which were shut down after the Fukushima disaster. The government’s position on nuclear energy is to maintain nuclear energy as base-load energy. But Abe did not push this, and did not mobilise political capital to accelerate the process.

So what is the Abe cabinet likely to deliver in 2015?

Abenomics and Futenma Marine Corps Air Base relocation pose serious challenges to Abe this year. These issues will require him to take more political risks and mobilise more political capital. This prime ministership needs the change to anew mode third time round and it will have to deliver tangible results beyond past expectation: consolidating economic growth and reaffirming Japan’s commitment to the US alliance and international security. Abe will have to revise security guidelines and enact national security laws for collective self-defence.

Abe must find a solution to the Futenma problem in Okinawa. Abe’s LDP was defeated in all four districts in Okinawa because of the issue of the base relocation. The frustration among the people in Okinawa is mounting. Abe must devote himself to closing the widening gap between Tokyo and Okinawa. In the meantime, failing to address the issue may undermine the confidence of Abe’s commitment to the alliance.

The 70th anniversary of the end of the Second World War will also pose a big challenge for Abe in 2015. It will require him to reconcile and balance strong domestic pressures from his nationalist political supporters with international expectations. The anniversary statement will require much from Abe: both in terms of his ability to handle the issue with care and balance and also in terms of expending his political capital.

In 2015 Abe’s success will be measured by his actions, far more so than his words and far more so than in the past. Actions will be the measure of Abe third term success.

Nobumasa Akiyama is Professor at the Graduate Law School and the School of International and Public Policy, Hitotsubashi University.

This article is part of an EAF special feature series on 2014 in review and the year ahead.