Since the end of the Cold War, Japan and China have steadily developed their defence and security cooperation on top of maintaining their long-term economic and political partnership.

The continued efforts to sustain and advance this security cooperation suggest that, despite growing Sino-Japanese strategic rivalry, defence relations could get back on track if they are carefully managed by policymakers of both countries.

Defence exchanges between the two nations began in the mid-1990s. Both countries agreed to promote confidence-building measures or practical cooperation through reciprocal visits of high-ranking military officials, regular exchanges between members of military academic institutions and naval port visits.

This does not mean that there were no political and security problems between Japan and China in this period. The National People’s Congress’s passing of the Law on the Territorial Sea and Contiguous Zone including the Senkaku* Islands in 1992 and its series of nuclear tests from 1995 to 1996 during the Taiwan election campaign raised tensions. And former Japanese prime minister Ryutaro Hashimoto’s 1996 visit to the Yasukuni Shrine, which houses the souls of Japan’s war dead, including 14 Class-A war criminals, provoked condemnation in China.

During the 2000s, bilateral relations between Japan and China were described as ‘politically cold, but economically warm’. Even as their trade relations continued to grow, political controversies continued, including more Yasukuni visits and massive anti-Japan protests in China.

Despite these difficulties, or perhaps because of them, Japan and China have always sought a pragmatic way to stabilise relations. In February 2001, both countries agreed to provide prior notification before conducting oceanic research activities in the other’s claimed exclusive economic zone—though China later failed to meet this agreement. In April 2007, the two nations also announced that they would jointly create a maritime communication mechanism in order to prevent an unexpected accident at sea.

One of the most important developments in the post-Cold War era was that both countries no longer relied on cooperation based on ‘neighbourly friendship’, sustained by personal relations between politicians or economists. They instead sought to establish more mature relations by expanding bilateral, regional and global cooperation.

Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s first ‘ice-breaking visit’ to Beijing in October 2006 was followed by several positive developments, including reciprocal naval port visits, joint training for search and rescue missions, and expanded dialogue between their respective militaries. After the 2008 Sichuan earthquake, the Chinese government even requested an aid airlift by the Japanese Self-Defense Forces — although China later withdrew that request after massive protests from the public.

Until just before the Senkaku incident in September 2010, when two Chinese and Japanese boats collided in disputed waters, the Sino–Japanese defence and security relationship was relatively good. But the Senkaku incident suddenly changed the cooperative framework between Japan and China. And after Japan’s nationalisation of the Senkaku Islands in September 2012, Japan–China defence exchanges were entirely suspended. But, even after all that, both sides sought to resume dialogue, although such efforts were often interrupted by domestic problems.

In Japan, the weak governance of the Democratic Party of Japan administration, including its frequent, rapid changes of prime minister, made it difficult to continue a sustainable dialogue with China. In China, Xi Jinping’s accession to power in 2012 caused a power struggle that made it difficult for Chinese leaders to take a ‘soft’ approach toward Japan.

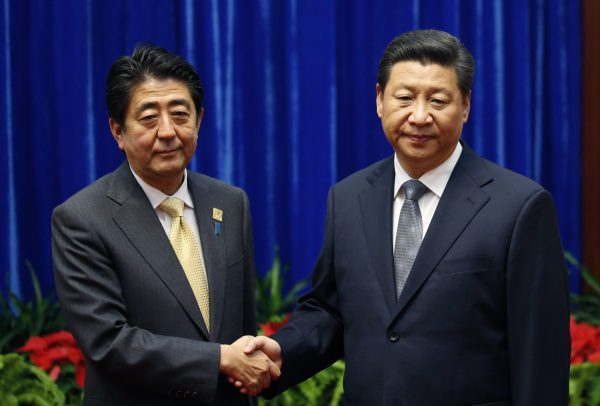

As President Xi consolidated power, and as Abe’s new Liberal Democratic Party government stabilised Japanese politics, China moved to resume the dialogue. In November 2014, a Japan–China leaders’ meeting was held for the first time since 2012 alongside the APEC meeting in Beijing.

So how can Japan keep up the momentum for better Japan–China relations?

First and foremost, both nations need to put the recent maritime disputes into a broader context, as they constitute only one part of the overall relationship. Cooperation — even if symbolic — could help generate a friendlier atmosphere, which is necessary to promote more substantial bilateral cooperation.

It is also essential for Japan to maintain and enhance credible deterrence capabilities as a foundation for confidence-building measures with China. Enhancing the US-Japan alliance is of particular importance. The revised US–Japan defence guidelines strengthen US involvement in regional contingencies, including in a so-called ‘grey-zone dispute’ — that is, an infringement that does not amount to a full-blown armed attack. This will send a clear signal to China that any provocation in the East China Sea could potentially invite US military involvement.

At the same time, Japan should continue to explain to China that the revised US–Japan defence guidelines do not intend to change the status quo by force, nor change Japan’s exclusively defence-oriented posture. Japan should also keep persuading China to refrain from provocative behaviour, including sending ships to Japanese territorial waters or establishing artificial islands in the South China Sea. After all, it is only a continuous mixture of engagement and hedging that can help to normalise Sino–Japanese defence relations, and therefore ensure future stability in the Asia Pacific.

Tomohiko Satake is a Senior Research Fellow at National Institute of Defence Studies, Tokyo. The views expressed here are solely those of the author and do not represent the views of NIDS or the Ministry of Defense, Japan.

* Called Diaoyu by China (Editor’s note).