The LDP’s solid majority in parliament and its strong leader have given Japan some political stability, something it has not seen since the Koizumi administration. Before Abe became prime minister in 2012, six prime ministers came and went quickly — each serving on average one year in office. In 2006, Abe was one of those six. He waited six long years to get back in office.

But Abe must clear a party hurdle to continue as prime minister. In Japan, a majority party president is automatically endorsed as prime minister. Abe was elected LDP President in September 2012 for a three-year term. He will complete his term in September 2015.

The LDP rules allow a member to continue as party president for a maximum of two terms, a total of six years. To run, a candidate must be endorsed by 20 LDP parliamentarians. Two rounds of elections are held: in the first round parliamentarians and party members vote for running candidates. If no single candidate gets a majority in the first round, then a runoff takes place. In this round only the two top candidates from the first round run and only LDP parliamentarians vote.

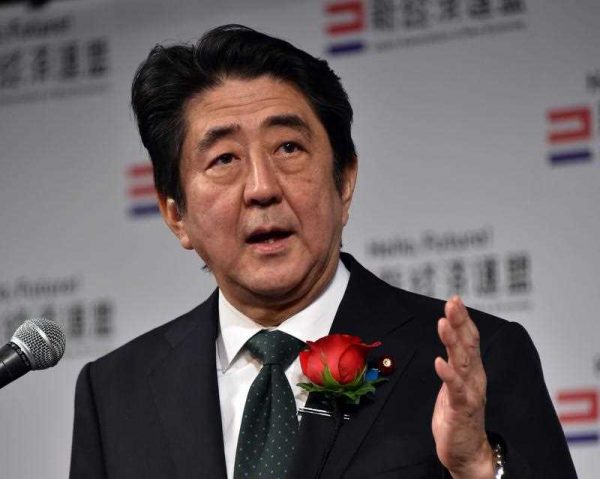

In the 2012 election, no candidate won a majority vote in the first round. Shinzo Abe and Shigeru Ishiba emerged as the two top winners. No one expected Abe to win, as Ishiba had more votes in the first round. But at the parliamentary level, against all odds, Abe defeated Ishiba and became leader of the LDP, which was then in opposition. Abe led the party to a historic win in the December 2012 generation elections, bringing the LDP back to power after three and a half years of Democratic Party of Japan governments under three different prime ministers.

The September presidential election is less exciting. It is almost certain that Abe will continue as party president and thus prime minister. There won’t be public speeches or television appearances by competing candidates, nor will there be party room manoeuvrings and factional bargaining for party positions and cabinet posts. The latest reports suggest that all seven factions within the LDP favour Abe and none is going to run its candidate to oppose Abe.

The only possible exception is Seiko Noda, a high-profile female politician and senior party member who has served in high-ranking party positions and was a minister in the Obuchi government (1998 –2000). She may yet withdraw or not gain the required support of 20 parliamentarians to run. Even if she runs, it will be purely symbolic. Abe is sure to keep his position.

Of course, this is not the first time that a LDP leader might be elected unopposed. In August 2001, Junichiro Koizumi was re-elected party president unopposed. But Koizumi was a very popular prime minister whose approval ratings even exceeded the 80 per cent mark. In contrast, Abe’s popularity rate is low; ranging in the high 30s to low 40s, depending upon the poll. Interestingly, an equal percentage is opposed to his leadership.

So what makes Abe so strong within the party that no factional leader is challenging him this time? Even Shigeru Ishiba — who came close to winning in 2012 — has thrown his support behind Abe.

Popular support (or lack thereof) is not the main consideration this time around. Most party senior leaders acknowledge that, despite Abe’s somewhat low popularity ratings, he enjoys strong support of LDP parliamentarians. Running against him would therefore be an act of political suicide. Also, ‘Abenomics’ is still attractive to the general public and the business community, as the economy under Abe’s leadership has gained upward momentum.

Abe’s popularity declined in 2015 because of his push to pass a controversial security bill through the parliament. The bill was passed by the lower house in July and is likely to be passed by the upper house before the end of September. Any party disunity will likely weaken the prospect of the bill being passed. But even if the upper house blocks it, the lower house can still turn the bill into legislation with a two-thirds majority after a lapse of 60 days, when it returns to the lower house. There, the LDP has the numbers with the support of junior coalition partner Komeito.

Abe has positioned himself to retain party presidency and therefore the prime ministership until the next lower house elections. These are not due before the end of 2018. The upper house election in mid-2016 could be a critical point for Abe, as he knows well. It was soon after the August 2007 upper house election delivered a damning report card for the LDP that Abe stepped down as prime minister during his first stint in the top job. But the upper house elections are still a long way off, and politics makes strange and unpredictable trajectories — as the adage goes ‘even a week is a long time in politics’.

Purnendra Jain is a Professor in the Department of Asian Studies at the University of Adelaide.