With the onset of the global financial crisis (GFC) in 2008, central bankers looked set to enhance their rock star status. Pulling new policy tools out of the hat, such as quantitative easing, they engineered a famous escape from what at first blush looked like a certain second Great Depression.

In retrospect, the GFC has blown away the halo surrounding central bankers. They stuck resolutely to inflation-targeting in a rapidly globalising world where consumer price inflation was ceasing to be a robust marker of domestic business cycles. They misread the business cycle and refuelled asset bubbles. Macroeconomic policies are intended to fix cyclical downturns, not structural obstacles to growth. The real economy has not responded as expected to protracted, aggressive and unconventional monetary policy, now stuck at the zero-bound in major advanced economies for close to a decade. This is despite the fact that monetary policy transmission channels have traditionally been much stronger in developed countries. This may no longer be the case.

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) was one of the few major central banks that emerged unscathed from the GFC. It deployed macro-prudential tools to target asset bubbles, while Western central bankers were ignoring the problem. The Nobel Laureate, Joseph Stiglitz, remarked in 2009 that ‘if America had a central bank chief like Y. V. Reddy [RBI governor from 2003 to 2008], the US economy would not have been such a mess’.

Since the crisis, the RBI has held the view that India’s growth crisis is at its root structural and cannot be fixed by monetary policy. The G20 Framework for Strong, Sustainable and Balanced Growth has diagnosed that obstacles to higher global growth are structural, needing structural policy solutions. Private investment seems shy the world over, and monetary policy has not been the solution anywhere, even at the zero-bound.

India’s problems lie in its unpredictable tax regime, mounting infrastructural bottlenecks, dysfunctional governance, poor business environment for two major factors of production (land and capital), high levels of corporate debt and depressed global demand. The current account deficit and inflation have declined because of lower demand and international prices and not because underlying structural imbalances have abated.

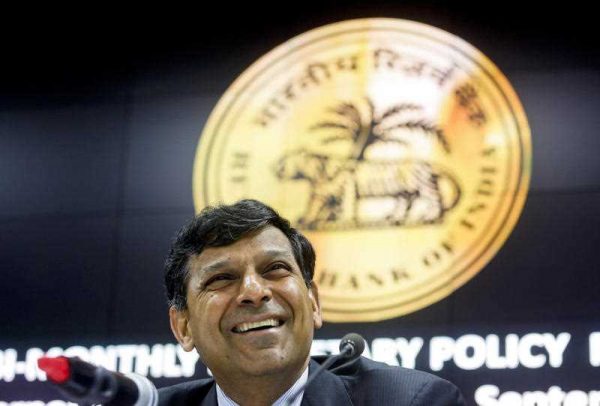

After a long pause, the usually pussyfooted RBI surprised markets by lowering its benchmark repo rate (the rate at which the RBI lends to private banks) by a frontloaded 50 basis points at its fourth bi-monthly monetary policy update on 29 September 2015. With recent declines in India’s consumer price index, a good case could no doubt be made for lowering interest rates if one were to go by the central banking mantra. Voices from the Indian Treasury were clamouring for lowering rates, as this would boost demand. But the central bank should keep three additional factors in mind.

First, lower rates are unlikely to provide a quick fix for the daunting structural challenges faced by the Indian economy. In these circumstances they could feed investment into riskier financial rather than productive real economy assets.

Second, savings typically increase during a business downturn because of a decline in consumption and investment. But savings are currently falling in tandem with bank credit. Should investment revive, a huge savings–investment gap could open up. Financial savings — that segment available for productive investment — have fallen dramatically. Bank deposit growth has declined in practically every successive quarter, from 21.9 per cent in the quarter ending March 2009 to 10.6 per cent in the quarter ending June 2015. Lower interest rates make financial savings even less attractive and weaken policy transmission channels in India since administered rates, such as on small savings and provident funds, set a nominal floor to deposit rates. They are also unlikely to spur investment unless structural impediments are addressed.

In these circumstances, there is a case for increasing savings and directing these to fill the large infrastructure gap through state-directed investment, much like under the Chinese model. Unlike China, India has the domestic demand to sustain relatively high growth even in a depressed global scenario, if structural constraints are addressed.

Finally, there are global policy spill-overs to consider. The US Federal Reserve has for some time been the de facto global central bank on account of the dominance of the dollar in the international monetary system. Its policy easing sends a tsunami of capital into emerging markets that washes back when it tightens. Can the central bank afford to ignore likely spill-overs of the expected Federal Reserve policy pivot, knowing that developing countries are the worst affected? Would it then be constrained to pivot on its own?

The RBI is one of the few institutions in India that works well. The rationale of current attempts to reconfigure its policy formulation processes seems baffling as it violates the golden rule that if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it. The RBI anticipated the use of macro-prudential policy tools to target asset bubbles in the run-up to the GFC. It has stuck to monetary rectitude in its wake, despite constant criticism that it was ‘behind the curve’, even as central banks in advanced economies flogged monetary policy to its limits and fuelled new asset bubbles.

After engineering the great escape from a second Great Depression, central bankers in advanced economies seem unable to engineer an escape from unconventional policies. The RBI stands out as virtuous in comparison, its policy arsenal intact and its gunpowder dry and at the ready.

Alok Sheel is the Additional Chief Secretary in the provincial government of Kerala. He was previously the Secretary of the Prime Minister’s Economic Advisory Council, India.

This article was originally published here in Business Standard.