This is their democratic right, but it may hinder further political reforms and democratisation in Myanmar.

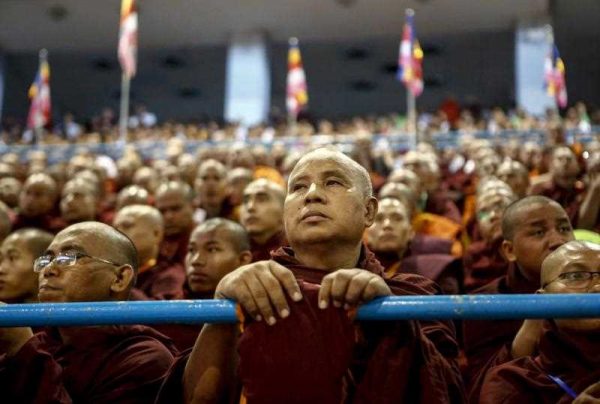

Buddhist nationalism has flourished since political reforms were introduced in 2011. Leading Buddhist monks have formed the Organization for the Protection of Race and Religion, generally known by the abbreviation ‘MaBaTha’, which has the aim of promoting Buddhist interests. MaBaTha monks and nuns have been the driving force behind, among other things, four controversial laws designed to ‘protect race and religion’. The aim of these laws is to protect Buddhist interests, but they are seen by some women’s rights groups and religious minorities as extremely discriminatory.

In the current election campaign, MaBaTha monks have lent their support to the governing party, the USDP, which represents the military regime. At the same time, MaBaTha has urged people not to vote for Aung San Suu Kyi’s party, the National League for Democracy, on the grounds that it is allegedly too Muslim-friendly. The generals have since the inception of the MaBaTha supported MaBaTha’s protectionist agenda. The election campaign is showing that Buddhism may legitimise authoritarian regimes if they are seen to be promoting Buddhist interests.

Demands for state protection of Buddhism have broad appeal in Buddhist countries and can easily be used to mobilise political support. Traditionally the relationship between the state and religion has been characterised by mutual dependence, and there is a strong feeling that it is the state’s task to protect Buddhism. In Thailand, the king has to be a Buddhist. And in both Sri Lanka and Myanmar it would be unthinkable to have a head of state who was not a Buddhist. Consequently, political power is bound up in religious affiliation.

The challenge is the place of religious minorities in states with a Buddhist identity. In several countries in the region, a pattern is developing where Buddhism is being used to legitimise the ruling political power, while ethnic and religious minorities undergo systematic exclusion. This political culture has been evident during this year’s election campaign in Myanmar, in which 88 candidates — many of whom were Muslims — were declared ineligible to stand for election. If Buddhist political players have contributed to the exclusion of religious minorities from the possibility of participating in democratic processes, Buddhism may be boosting authoritarian forces rather than contributing to democratisation.

While the Buddha preached radical ideas about salvation and equality, to claim that the Buddha was a democrat would be to read history backwards. Ancient Indian society had a hierarchical structure, and the Buddha did not challenge this structure directly. The prevailing concept is that of an ideal Buddhist king, who is not only expected to safeguard the monastic order through physical protection and material benefit but also prevent its moral decay. The sangha in turn is expected to offer ideological legitimacy to the state.

Many of the claims made by the MaBaTha in the 2015 election campaign fit into this traditional pattern of state patronage of Buddhism, which finds resonance in the wider public. In fact, calls for the protection of Buddhism have shown themselves to be particularly well-suited to electoral competition. The need to find a suitable ideology to rally for has paved the way for radical Buddhist nationalism in Myanmar.

Another key point in Buddhist political ideology is a formal divide between the state and the monastic order. In Myanmar (and Thailand), Buddhist monks are deprived of their political rights. The reason for this is in accordance with traditional Buddhist thinking: there should be a formal separation between the monks and political power. It means that the monks do not have the right to vote, form political parties, stand for election or sit in parliament. Myanmar’s half million monks potentially comprise a significant base of voters, and it is easy to believe that this rule was introduced by the generals in order to restrict the monks’ political activities.

Monastic disenfranchisement represents a political paradox. On the one hand it points to the privileged status of Buddhism within the Myanmar state. On the other hand, it represents a particular violation of basic political rights of monks and nuns. But this does not necessarily mean that monks feel deprived of their fundamental political rights or lack political influence. Many monks who fight for democracy think rather that their exclusion from formal political processes opens up new and more important opportunities for informal political influence, because they can preserve their religious authority precisely by not becoming ‘tarnished’ by party political activity.

Monks were central in mobilising opposition to the military junta in protests in 1988 and 2007. Many monks have also supported various student protests and signed calls for constitutional amendments. There are also strong Buddhist traditions of moral responsibility, justice, equality and willingness to work voluntarily for a common purpose. All these traditions are important for successful democratisation.

Buddhism may contribute to democratisation in Myanmar, but only if Buddhists make a stand for a new and inclusive Myanmar where ethnic and religious minorities receive protection and enjoy equal rights.

Iselin Frydenlund is a senior researcher at the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO) and the Norwegian Center for Human Rights, Faculty of Law, University of Oslo.

This article shows a fundamental misunderstanding of the political reality and democracy in contemporary Asia. In Myanmar, as well as in Sri Lanka and Thailand Buddhism is facing a formidable onslaught by Christian evangelical movements and Wahabi Islamic forces, both of which are well funded from overseas. Christians mainly from the US, Europe, Australia and South Korea, and Muslims mainly from Saudi Arabia are training and funding evangelists to infiltrate these countries. Thus, when they open up they are more vulnerable to such insurgencies. These insurgencies are not necessarily directly funded by governments but non-governmental agencies some of which infiltrate these countries as NGOs promoting freedom and democracy or as social welfare agencies. The Buddhists are feeling extremely vulnerable in the face of this onslaught because most of the poor in these countries are Buddhists and they do not have international Buddhist organisations with a lot of money to help them, while money and bribes from overseas play a huge role in threatenign the existence of Buddhism in these countries, the Buddhists are crying out for assistance from their own governments. The so-called Buddhist Nationalism is rooted in this socio-economic situation. Just because Buddhists are numerically superior does not mean they are in control of their economic destinies. Muslim and Christian minorities are often better off economically than the Buddhist majority because many are involved in business or reap the benefits of privileges they got under colonial rule. West’s human rights campaigners and democracy vendors simply do not understand this and this article is a typical example of that.

Its true that the Buddhist monks in Myanmar will have a serious influence not only in the upcoming election but also in the post-election scenario. Organizations like MaBaTha is raising voices for a strong Buddhist state wherein the minorities, particularly the Rohingya Muslims will have virtually no role and identity. Keeping this agenda in mind the monks have offered their support to the military backed USDP. And now it is crystal clear that the monks have signalled for an authoritarian regime in civilian disguise. The way the Rohingyas are being treated in Myanmar by the state and the monks; and the virtual silence of Asia’s democracy icon Suu Kyi on this matter is highly deplorable. All these pose a grim picture of Myanmar’s fragile democracy even before the election results declared. Therefore it is feared that the moves taken by the monks would derail the democratic reforms of Myanmar.

Dr. Makhan Saikia, Independent Political Analyst based in Delhi.

Dear Kal Sen,

Thank you for sharing your thoughts. I think you are pointing to something very crucial here, namely the fear that many Burmese Buddhists (but also Sinhala Buddhists or Norwegian Christians for that matter) feel in times of rapid social change. Rapid demographic changes and migration do alter societal structures, creating both challenges and opportunities. I very much understand your concern over the spread of global Salafism, and even aggressive Christian Evangelism. However, my concern is rather how we respond to such challenges from a Buddhist point of view, and in a way that does not threaten the very democratization process itself. I agree that religious freedom is a highly political and contested notion, and one which not necessarily leads to democratization. But excluding certain minorities from the very political process is certainly problematic if the aim is a well-functioning democracy. The ultimate question, in my view, is how you protect your religion in a way that also protects religious minorities. I think Buddhism as a religious system is particularly well-suited for this task.

When people are feeling threatened by social change, they often cling to their religious beliefs even more strongly as a way to reduce their sense of threat. Unfortunately,sometimes that increases their intolerance for what/who they see as the cause of their fears: typically those of a different faith, culture, or country/region. Witness what is happening in Europe now in response to the waves of Muslim immigrants flooding in from the Middle East, Afghanistan, Northern Africa, etc. The locals are sometimes all too willing to sacrifice their democratic rights for a greater sense of security. The religious or political forces in place all too often play on these fears rather than encourage their followers to at least accept the changes while still protecting their own interests. What ensues can be ugly and tragic ethnic/racial conflict, if not genocide, instead of welcoming the newcomers/those of a different faith as offering the opportunity for diversity, greater growth, and ultimately greater strength.

Bhuddism is inherently reactionary. Look at Thailand for example. It is one of the most powerful forces that is vehemently opposed to democracy.

If Lee thinks Buddhism is ‘inherently reactionary’ he should have his head examined. Does he think Christianity, Islam and other Abrahmic religions are progressive compared to Buddhism? Before talking bunkum about the Buddha’s teaching he should compare it with the criminal histories of the religions the representatives of which tried and are still trying to impose on the rest of the world their creator-god concept by overt and covert means. We know about the cruelties of the Inquisition and the burning of so-called heretics. The Catholic Church has been one of the most reactionary and corrupt institutions in the world. Democracy, liberalism, animal rights and atheism arose in Europe in opposition to the reactionary thinking of the Catholic Church.

In contrast the founder of Buddhism is the only teacher who said “Do not accept my teaching without independent verifying the truth of what I am teaching.” This is why Buddhism is not even considered a religion in the widely accepted sense but an enlightened way of living. Only Buddhism and Jainism stresses the need to protect as far as possible life in all its forms (both man and beast) and does not promote the idiotic view that the earth was created for man’s benefit.

It is stupid to liken the Buddhist teaching to what some people may do in its name.

Iselin and I have worked together on many similar fronts. I wish you addressed these dimensions: The attack on Buddhists in neighboring Bangladesh. The conversion of a Buddhist country Indonesia to islam using similar strategies affect how Burmese thinks.Rich foreign based NGOs and evangelical groups in Srilanka converting poor Buddhist even Catholics is a classic situation as you are aware.As a criminal lawyer I would state that right of self defence is available if you are threatened .These laws may not be the answer,yet we need understand things in the way Kalsen stated above.

Dear Prasantha, Ayubowan!

Thank you for this. Yes, I know that many people share this concern, and yes, these concerns have to be taken seriously. To what extent legal regulation is the answer, is another question. Changing religious demographics is certainly an important issue. What I wanted to address in my short piece is that strong Buddhist forces support the military regime. That is the question at stake here.

Dr, Iselin Frydenlund of PRIO, Oslo, if I remember correctly, entered the study of Buddhism at a time when Norway’s intervention in Sri Lanka as a peace-maker was going nowhere. She did her initial field work in Sri Lanka and in her report (again if I remember correctly)recommended that it is necessary to win over the Buddhist monks to influence Sri Lankan politics. It was a time when the Norwegian peace-broker, Erik Solheim, had failed to influence Vellupillai Prabhakaran, “the latest Pol Pot of Asia” (New York Times)to agree to the proposed international peace deal marketed by him. Clearly, the so-called “Sinhala-Buddhist state” had gone a far as they could to go along with the Norwegian-led peace proposal to appease the Tamil minority but the path to peace was blocked by the intransigent politics of the Tamil “Pol Pot”. Ms. Frydenlund, however, advanced the pop theory that the main stumbling block to peace in Sri Lanka was the politics of Buddhism.

I think she has misread the nature of Buddhist politics. Buddhism is reacting defensively and sometimes even aggressively to the extremism of the minorities who are demanding, through violent politics, division of their state or change of constitutions to acquire a disproportionate share of power. The threat of separatist movements to Myanmar is as a great as the Tamil separatist movement to Sri Lanka.

Norway failed in Sri Lanka because misguided Erik Solheim sided with the Tamil separatists even when they sabotaged the peace deal brokered by him. Besides, the general tone of Mr. Frydenlund proposition that Buddhism has developed into authoritarianism is not validated by the events in Sri Lanka. The greatest achievement of the Sinhala-Buddhists is in the restoration of democracy to the Tamils who were denied their basic right to go to school, or to exercise their free will in politics, or to contest in elections without the consent of the Tamil Pol Pot. Without endorsing any form violence, it must be emphasized that Buddhism has acted aggressively at times mainly as a reaction to the excessive thrusts of minorities to grab a disproportionate share of power and positions. Minorities who exceed the accepted limits of peaceful co-existence cannot expect the Buddhist majorities to roll over and watch their traditional rights being wiped out.

Whether in Europe, Africa or Asia the problem of the majority-minority relations has come to the fore. The pattern is clear: established majorities continue to react defensively and aggressively to protect their cherished values against violent threats / invasions of minorities.

Dear Mr. Mahindapala,

Long time no see! What a small world. Thank you for sharing your thoughts. First of all, I would like to clarify an important misunderstanding. I argued the opposite of what you suggest I did. My main point in my writings on monks and the peace process in Sri Lanka is actually that the Norwegians should have included the monks in a broad consultation process. I have been highly critical of the secularist nature of that peace process since the beginnings. The situation in Myanmar and Sri Lanka is very different. Buddhist politics in Sri Lanka is (among other things) a baby of Sri Lanka´s strong democratic tradition, a tradition that showed its strength during this year´s two elections. Sri Lankans have every reason to be proud of this. The Jathika Hela Urumaya, in my view, did an important job in challenging authoritarian tendencies. The case of monks in Myanmar is very different as the country has been under military rule since 1962. The choices made by Buddhist monks in this new transition context is highly important. This is not only about minority-majority relations; it is also about the Constitution, free and fair elections, political and civil rights to people living in Myanmar, the Rule of Law etc. To the extent that Buddhist monks support forces that work in favour of military rule, yes, I think this discussion is worth having. And again, Sri Lanka´s experience of Buddhist politics is very different. And just for the record: I have never argued for or against Buddhist politics as such.

It is misleading to suggest that Buddhist nationalism is hindering democratisation. Religion plays an important role in many democracies. Buddhists form the majority of the population in Myanmar and it is their democratic right to select whichever politicians they feel best represent their interests. The ‘tyranny of the majority’ is an unfortunate side-effect in all democracies.

You are also wrong to say that the USDP “represents the military”. The USDP is certainly affiliated with the military, but the strength of their relationship has varied. The military represents the military, in parliament and elsewhere.

Iselin’s view on “democratisation” and Buddhist Nationalism and her interpretation of Gautama Buddha as a great democrat needs certain clarifications. Buddha’s teaching and dhamma originates over 2500 years ago. Trying to draw parallels with the current parliamentary representative system which came emerged less than 5 centuries ago with Buddhas teaching clearly explains the narrow view of the writer. Siddartha was a prince, after enlightenment in his teachings Buddha prescribed a code of conduct for rulers which is known as “dasaraja dhamma” and consists of 10 principles. A fundamental principle behind the code is “PARTICIPATORY DEMOCRACY” not the REPRESENTATIVE DEMOCRATIC model practiced by nation states at present. It is high time that there is academic research initiated to study the impact of Buddhism’s and dhamma’s in shaping the Asian civilization. Buddhism went from India to China; the passage the scholarly monks traveled was the path that created the Silk road for trade and commerce. But unlike many other religions Buddhism was never traded as a faith.

This lengthy piece amounts to almost nothing- for the author fails to give any precision on the quantitative importance of Ma-Ba-Tha and of the weight of ‘recommendations’ of extremist monks in the election choices. I fully agree with Kal Sen on the misconceptions in this article, and on the naivete of the author. She replies to Kal Sen “excluding certain minorities from the very political process is certainly problematic if the aim is a well-functioning democracy. The ultimate question, in my view, is how you protect your religion in a way that also protects religious minorities”- certainly a Westerner’s view. I would object to that :1) the fact of being a minority has never been a warrant to be included in democratic process. On the contrary many political minorities e.g. nazi, bolcheviks, or anarchists play the democracy game until they are strong enough to seize power and end that democracy; 2) there is no example in history of a religion that has been succesful in protecting itself while protecting opposing minorities…especially when said minority promote openly proselytism and active fight against ANY other religion; and 3) what is the author model of a well-functioning democracy- it would be interesting on how it could be present in Asian cultures and how it compares to the mainstream acception of the word in Myanmar and in the region.