The India–Pakistan relationship is one of the world’s most important. Since the partition of India in 1947, the story of India–Pakistan relations has been one of political rivalry, mistrust, active interference, tension and unrealised economic potential. Bad politics have dominated and the economic relationship is trivial despite its potential.

India is looking and acting East. The highly integrated production networks in East Asia are attractive to join, as Indian manufacturers and service suppliers seek opportunities to tap into existing supply chains to realise their comparative advantage. Myanmar’s strategic location, connecting East and South Asia, can assist that process with an orderly political transition following its landmark elections of 2015.

But the massive unrealised potential in South Asia remains a drag on India and Pakistan both. If living standards in Pakistan and elsewhere in South Asia do not rise, the challenges of poverty and extremism will continue to stalk regional stability.

The factors that drive the economic interaction between countries are scale and distance. The scale of India’s and Pakistan’s economies and the distance between them suggests that their trade should be 10 to 20 times higher than it actually is. That’s a lot of wasted economic potential.

The contrast with East Asia is stark. In East Asia, the story has been one of growing economic interdependence among neighbours who, though they have residual mistrust, unresolved history, territorial disputes and tensions that flare up from time to time, have become big economic partners. So far the tensions in East Asia have not affected trade and investment to any significant degree and have not escalated to serious conflict. The economics have dominated the politics.

The Japan–China relationship is an important case in point. Trade both ways and investment from Japan boomed, all while anti-Japan protests and boycotts flared in China and leadership visits were suspended. The China-Japan trade relationship is the third-largest globally and Japan is the largest investor in China after Taiwan.

Another case is the Taiwan–China cross-Strait relationship. When China and Taiwan acceded to the WTO in 2001, Taiwan committed to gradually removing trade restrictions aimed at the mainland. Previously, trade from China had to go through Hong Kong or other entrepots to arrive in Taiwan. Dubai plays that role in South Asia with an estimated US$4.7 billion of trade in 2013-14 between India and Pakistan taking the very long way round.

With China granting most favoured nation (MFN) status to Taiwan, trade with the mainland went from 3.6 per cent of total Taiwanese trade in 2000 to over 22 per cent in 2014. The PRC is now by far Taiwan’s largest trading partner. Investment and people flows have increased. Although the economic relationship had been held hostage to the political security concerns, just like in South Asia, affording equal best treatment, or MFN status, across the Strait was the breakthrough.

India granted Pakistan MFN status in 1996, but Pakistan is yet to reciprocate. Mohsin Khan explains in this week’s feature essay that ‘[o]nly 16 years later in February 2012 did the Pakistan government declare it was ready to grant MFN status to India’. That opportunity was missed due to Pakistani domestic opposition.

‘Because of controversy surrounding the term, MFN is referred to as ‘Non-Discriminatory Market Access’ (NDMA) in Pakistan’, Khan also explains. And Pakistan has had trouble mobilising the political support to grant NDMA, postponing decisions in 2013 and 2014. Not all of these delays have been due to internal opposition in Pakistan. Khan points out that ‘the Pakistani government … [also] received a request from India to postpone its NDMA until after the Indian elections’.

The time may now be ripe for Pakistan to break the deadlock and grant India NDMA. There is no major political party in Pakistan opposed to the move. The Pakistani military has historically been opposed to normalising economic relations with India. But according to Khan, it now ‘realises the need to explore all avenues for improving the economy, including expanding trade with India’.

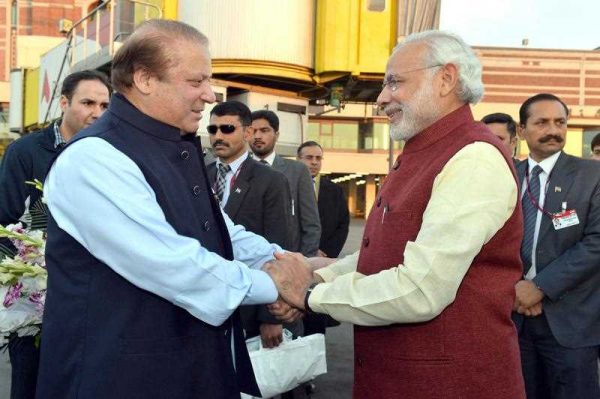

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi made a surprise visit to Lahore on Christmas Day last year to meet Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif on his 66th birthday and to celebrate Sharif’s granddaughter’s wedding day. The historic visit followed an agreement earlier that month to initiate a comprehensive dialogue process. Things are looking up.

Pakistan’s granting MFN or NDMA to India would be a watershed. But it will only be the start in building a productive economic relationship. Infrastructure will need to be built, borders opened up and attitudes in both bureaucracies will need deep cultural change.

Deepened economic linkages and exchanges alone won’t fix all the problems between India and Pakistan, but they will help vastly. Having businesses invested in the other country will give both sides stakeholders and vested interests in keeping relations stable — something that’s been almost totally absent to this point. Once economic ties start to thicken, they will constrain bad behaviour between the countries.

While any number of unwelcome disruptions could derail a breakthrough on MFN this year, the forces of economic gravity are pulling the two countries together. These forces will be more resilient to political counter-forces if they are given free play in a world where India and Pakistan seek engagement with each other at the same time as they engage with East Asia and the rest of the world.

The EAF Editorial Group is comprised of Peter Drysdale, Shiro Armstrong, Ben Ascione, Ryan Manuel and Jillian Mowbray-Tsutsumi and is located in the Crawford School of Public Policy in the ANU College of Asia and the Pacific.

After almost 70 years of conflicts one can hope that these two countries will finally begin to interact in a more constructive way. The real beneficiaries of growing trade would be the citizens of both countries.