This revisionism is likely to become the primary source of tensions and potential conflict in Southeast Asia.

Nowhere are China’s revisionist aims more evident than in the South China Sea and the upper reaches of the Mekong River, which straddles southern China, Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam.

In the South China Sea, tensions are mounting because of Beijing’s controversial claims over a string of reefs, shoals and fishing areas that are closer to the Philippines, Vietnam and Indonesia than mainland China. China has constructed artificial islands out of these small rocks, placed military equipment on them and even used them for passenger flights as a way of cementing its claims.

The Philippines has openly opposed Beijing, but Vietnam has remained non-confrontational because Hanoi relies heavily on China for trade, investment and economic development. The rest of the South China Sea claimants — Taiwan, Brunei and Indonesia — have mostly avoided a direct spat with China.

But Indonesia can no longer remain removed from the conflict. On 19 and 20 March Indonesian authorities detained a Chinese fishing trawler and its eight-member crew for trespassing in Indonesia’s exclusive economic zone off the Natuna Islands. In response, the Chinese Coast Guard intervened and rammed an Indonesian vessel to free the fishing boat. The incident sparked diplomatic outrage from Jakarta, embarrassing the Chinese.

The incident is part of a trend of growing Chinese belligerence that is illustrated by China’s unwillingness to take part in drafting a Code of Conduct in the South China Sea between ASEAN and China.

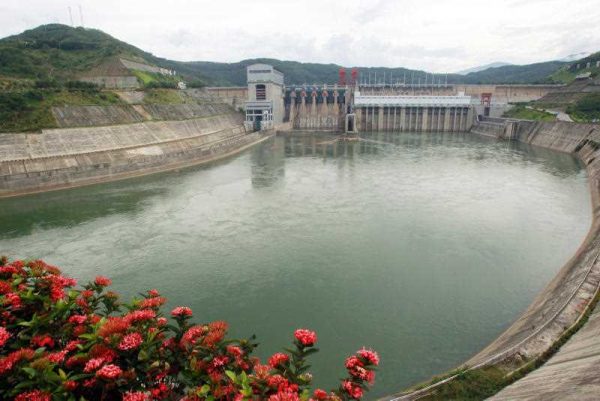

In the Mekong region of mainland Southeast Asia, China has similarly handed itself unilateral political power by manipulating natural waterways through the construction of a row of upriver dams.

As the Lower Mekong countries are suffering their worst drought in decades, China has been releasing water from its upstream Jinghong Dam for almost a month from 15 March in an ostensibly benevolent act. Yet this decision is motivated, at least in part, by a desire to grease the inaugural Lancang–Mekong Cooperation (LMC) summit among the six leaders of the Greater Mekong Subregion.

While China’s water discharge is a temporary respite for downstream countries, it shows that the Lower Mekong region has become dependent on China’s goodwill and generosity.

The Mekong, which the Chinese call Lancang, is Southeast Asia’s longest river. It provides livelihoods and habitats for riverfront communities and natural wildlife covering more than 60 million people through the Mekong mainland countries.

China’s damming of the upper Mekong has long been considered a geopolitical risk for the downstream states and a source of potential conflict for the entire Greater Mekong Subregion. That risk has become more serious because of climate change and the rapid development of the Mekong mainland, which now requires more water than ever.

Given its leverage over the downstream countries, China has been eager to convene the LMC summit in Sanya, Hainan province. Beijing has announced a combined loan and credit package worth US$11.5 billion for development projects in the Mekong ranging from railways to industrial parks. Beijing will also set up a water resource centre and fund poverty alleviation projects to the tune of US$200 million, with another US$300 million for regional cooperation over the next five years.

Chinese Premier Li Keqiang noted that these plans were part and parcel of China’s own development strategy around the One Belt, One Road initiative, and called for greater trust-building between China and the Lower Mekong countries.

What is significant here is that the LMC summit is effectively pushing aside the longstanding Mekong River Commission (MRC). The MRC was set up by Cambodia, Laos, Thailand and Vietnam in 1995, with international expertise and funding assistance, to manage river resources under international conventions and protocols governing major global waterways. Myanmar and China are dialogue partners of the MRC but Beijing has deliberately marginalised the commission, emphasising instead its own version in the LMC.

Given its size and location atop the river mouth, China can block the Mekong waterways at will. It has completed six of 15 planned dams. The downstream governments, particularly those of Cambodia and Vietnam, are either too beholden to or dependent on Beijing’s generosity and policy decisions to cry foul. Of course, other countries, including Laos, have also constructed dams on the Mekong. The Mekong dams are not simply a case of China imposing unilateral leverage and power over the rest.

Yet with Laos’ increasing economic dependence on China, and the Thai military government’s overt pro-Beijing posture, China has become a Mekong regional patron of sorts. Cambodia similarly relies on China for development aid and foreign investment. For its part, Vietnam takes a muted stand both on the South China Sea and the Mekong mainland.

Myanmar is the spanner in China’s Mekong designs. Under a newly elected civilian administration, led by Aung San Suu Kyi, the government in Naypyitaw may not be as forthcoming.

While it is difficult to deny that the Mekong mainland is effectively China’s backyard, this situation could change down the road if Thailand returns to democratic rule and joins hands with democratised Myanmar.

By being so aggressive in both the Mekong mainland and the South China Sea, China may end up forcing smaller states that want to avoid conflict into a regional alliance against it. To avoid stirring up a united neighbourhood opposition, Beijing would do better to play a major role in crafting rules and institutions in concert with others in the region.

Thitinan Pongsudhirak is Associate Professor and Director of the Institute of Security and International Studies, Faculty of Political Science, Chulalongkorn University.

I will not touch upon the South China Sea issue as it is a much more complicated global topic that involves not just China and ASEAN. I am just curious why is the author so against the cooperation between China and its neighbours in the Mekong sub-region? I have only limited knowledge regarding the geopolitics in the area so I will assume every fact presented by the author as correct.

Fact 1: China controls the upper stream of Mekong River and uses it to its advantage to further China’s national interest.

There is no real evidence presented by the author to show how China “bullies” the downstream nations into submission with its control of Mekong River, although it is totally possible that this case is used as diplomatic leverage in various negotiations. However, nation is not charity and all nations utilize whatever advantages they have for their national interest. Did Gulf countries not use their oil reserve to pressure international community for their conflict against Israel in the 70s and 80s? In my opinion, as long as China does not do things that will truly threaten the daily lives of downstream people (like what India just did to Nepal), this level of diplomatic play is acceptable.

Fact 2: China advocates its own LMC summit for dialogues between countries in the sub-region.

Have we not already discussed stuff like that before? Oh, it was about the AIIB. Which international law dictates that as long as there is one organization for something, it gains total monopoly over the topics it covers and no other nation is allowed to set up organizations for the same topics? Since there is ADB, AIIB should not be allowed? Since there is MRC, LMC should not be allowed? Why are LMC and MRC competitive to each other? Can’t they be complimentary? Again the author offers no answer to this.

Fact 3: Countries around China are growing more dependent on it.

I have mixed feeling for this. From China’s perspective, this of course is a good thing. From neutral perspective, I would suggest the countries be more diversified. However, for all these years, I have never seen ppl criticizing the US alliance system and how countries like Japan and Korea are way too dependent on US for their economy and even survival! Now China’s neighbours are just becoming a bit more economically dependent on China and we are supposed to give a fuss over it? Is it purely because it is China we are talking about, not US, not Japan, not EU?

At last, none of things described by the author regarding Mekong sub-region can be considered “aggressive” in my opinion (the most aggressive is the LMC, really?). If the author holds inherent bias against China, then I don’t think any constructive discussion can be established.

I doubt that China was ’embarassed’ by the so called diplomatic row with Indonesia. Rather, I suspect it will say the South China Sea is part of a greater China and continue to do as much as it thinks it can get away with short of an all out shooting war.

As for the Mekong River flow issues, China is already playing ‘a major role’ in rewriting the rules by calling the LMC. The strong get to dictate what rules those less strong have to follow…..unless the other countries refuse to participate. Will they risk their economic lives on confronting China like that?

Jokowi’s former foreign affairs advisor, Rizal Sukma, has just published an op-ed in the Jakarta Post on the incident the author of this post has referred to.

Sukma is now ambassador to the UK. This is not the first time an Indonesian diplomat serving abroad has published in the English-language press on an issue not directly related to his/her posting. The minister in Indonesia’s Beijing embassy, for example, published his views on Indonesia’s relations with Australia during the drug trafficker execution drama early last year. Jakarta-based Foreign Ministry officials also often publish op-eds in the Jakarta Post. Publishing in the vernacular press doesn’t seem to hold the same attraction.

One would of course like to know whether Jokowi asked Sukma to write on the Chinese fishing vessel incident, but it cannot be assumed that he did.

Sukma called for China to acknowledge Indonesia’s EEZ around the Natuna islands. He also reiterated Indonesia’s well-known position that it was not a claimant to territory in the South China Sea. This enables Indonesia to stake out the role of ‘mediator’ at some favourable time.

Indonesia currently does not take sides in any territorial dispute in the South China Sea. But Indonesian policy-makers may have to give some thought in the future to whether it will be better for Indonesia if China acquires sovereignty over all the islands and ‘features’ in the area or if fellow ASEAN members establish or retain sovereignty at least over some of them.

I find that this post biased and it does not seem to be based on factual analysis. Building dams along the Mekong River, for example, has been or is being done not only by China but by almost every country which the river passes through, while he author seems to suggest that only China has done it. China has built many dams in many of its own rivers, not just on the Lancang river.

China is not alone in terms land reclaimation in the South China Sea, but the author seems to want to create an impression that it is alone.

Perhaps, the East Asia Forum editors should be aware of this and should not allow misinformation to be presented by anyone!

The author has obviously taken sides. The author makes far too many assumptions and writes in cliches. How unfortunate. Perhaps you are completely wrong as to the intentions of China with respect to activity beyond their borders, wherever their borders lay.