Never before has politics in Vietnam been so reduced to the choice between two individuals.

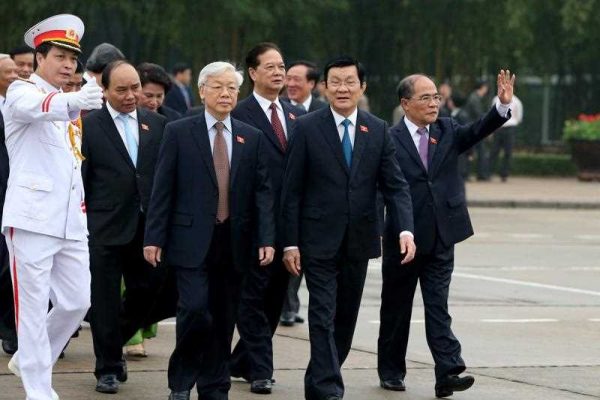

These two leaders were VCP General Secretary Nguyen Phu Trong and Prime Minister Nguyen Tan Dung. It is widely believed that Trong is a conservative who leads the pro-China faction, while Dung is a reformer who advocates pro-US policies. With Trong re-elected and Dung retiring, the expectation is that Vietnam will slow down economic and political reform, stop its pivot to the United States and move closer to China.

But the reality is far more complex. Predictions that reform in Vietnam has plateaued are premature. Trong is a conservative but at times he can behave like a reformer. He views the survival of the VCP as the primary mission of Vietnamese policies, but he has also promoted many modernisers who place national development before and above Party survival. Trong’s approach to China is soft in public but firmer behind the scenes. He is cautious about relations with the United States but he also supports closer ties with Washington and joining the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP).

Dung is no less complex and contradictory. He pronounced strong reformist views but prioritised preserving the monopoly of the VCP. What’s more, Dung sat at the apex of a vast rent-seeking network that employs the authoritarian state as a way to make money. His approach to China blended nationalist rhetoric and dramatic action with economic engagement.

The reformist–conservative dichotomy is too crude to depict Vietnamese politics. Although Party survivalists and nationalist modernisers dominated the country’s leadership from the late 1980s until the late 1990s, rent-seeking is now a powerful third force that permeates every aspect of the party-state. By the mid-2000s, rent-seekers had become the most influential among these three groups. Dung’s assumption of premiership in 2006 epitomised this trend.

Shortly after being elected VCP General Secretary in 2011, Trong launched a major campaign aimed at uprooting corruption. The main target of this anti-graft drive was Prime Minister Dung. But contrary to popular speculations, the subsequent bipolarity in Vietnamese politics was not one of conservatives against reformers, the Party against the government or the pro-China wing against the pro-US faction. The main fault line cut across all these dichotomies.

Although the key choice at the 12th Party Congress was between two individuals, the key contest was between two broad coalitions. Dung’s allies were mostly rent-seekers, modernisers and moderates. Trong was backed by an even more heterogeneous coalition that comprised Party survivalists, modernisers and moderates, with only some rent-seekers in the mix.

While most conservatives supported Trong, the modernisers were split between the two leaders. The Dung–Trong rivalry presented an impossible dilemma for the modernisers. Each of the two leaders represented a chief stumbling block on the road to reform. While Trong espoused an ideology that emphasised state control and state ownership, Dung embraced a rent-seeking state that lives by extracting funds from society.

One of the very few individuals who ventured out to the public in support of Trong at the 12th Congress was the moderniser Vu Ngoc Hoang, a senior vice-chair of the VCP Central Propaganda Commission. In a recent interview, Hoang suggested that Vietnam should temporarily aim at becoming something like an advanced capitalist country because this stage is closer to socialism than a state dominated by rent-seeking interests. The case of Hoang is illustrative of a larger phenomenon. Trong owed a critical part of his defeat of Dung to those modernisers who were committed to fighting rent-seeking.

The end of the Dung–Trong rivalry at the 12th Congress ushered in a new era. Vietnamese politics remains a mixture of three policy currents represented by Party survivalists, nationalist modernisers and rent-seekers, but the mixture has changed shape.

Compared to the previous configuration, the influence of rent-seekers has fallen while that of modernisers has edged higher. Party survivalists are also represented less strongly in the new leadership. Although rent-seeking may continue to dominate in the VCP Central Committee, modernisation is the most influential policy current in the Politburo for the first time since doi moi.

In addition to the leadership change, two other trends also suggest that Vietnam’s politics and economy will be more liberal in the years to come. As identity and interests diversify within the ruling class, the VCP will have to rely more on legitimacy to stay in power. This will push the party-state to be more responsive to popular demands.

Pressure also comes from outside Vietnam. As the conflict with China in the South China Sea intensifies, anti-China nationalist sentiments will rise in Vietnam. While Hanoi will continue to keep its options open, it will increasingly seek support from China-wary powers, most notably the United States and Japan. Some adjustments in the political and economic system will have to follow this foreign policy shift. The TPP is a case in point.

Continuing a trend that started in the late 2000s, Vietnam will veer farther — but not too far — from China, and closer — but not too close — to the United States.

It would not be surprising if Hanoi and Washington upgraded their relationship to a strategic partnership within the next five years. It may be unrealistic to expect big changes in Vietnam’s political and economic policies in the years to come, but reform will continue in multiple small steps.

Alexander L. Vuving is a Professor at the Daniel K. Inouye Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies, Honolulu. The views expressed in this article are his own and do not represent those of the US Government, the US Department of Defense or APCSS.