The authoritarian rules of the game that have held sway since the beginning of the modern reform era are steadily breaking down. For all of the problems associated with China’s existing system of authoritarianism, worse consequences will emerge as these rules give way.

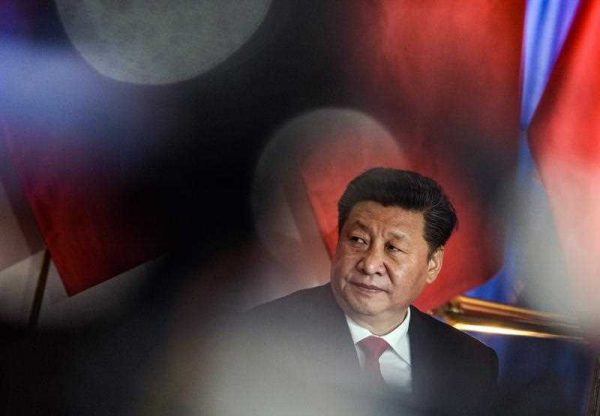

Since Xi Jinping’s rise to power in 2012, there has been a strand of opinion that argues that Xi is consolidating China’s existing authoritarian system. Adherents of this position acknowledge that Xi is tough. That he is harsh. And that he is riding roughshod over state and society alike with a harsh anti-corruption campaign and political crackdowns. But, so this analysis goes, tough times call for a strong leader. They argue that Xi is addressing the dangerous weakness and ineffectiveness that characterised the Hu Jintao administration. He is centralising power. And he is building new institutions to govern China. Naturally, these will be highly illiberal and strengthened authoritarian ones.

Such trends are alleged to reflect a renewal of China’s authoritarian state. These arguments are not entirely without merit. With respect to the Party disciplinary apparatus, for example, one could single out recent efforts to strengthen the power of central disciplinary authorities by establishing offices in all central-level Party organs and state-owned enterprises, and strengthen their control over provincial disciplinary chiefs, as signs that Xi is bolstering China’s authoritarian institutions. With respect to the judiciary in China, one could point to recent efforts to establish circuit tribunals of the Supreme People’s Court in regional centres like Shenzhen and Shenyang and to vest provincial courts with control over local court funding and personnel decisions

One could argue that these developments reflect the evolution of China’s system of governance into a more centralised, more institutionalised authoritarianism. But this would be incorrect. The new trajectory of China’s governance is fundamentally different, representing a break with post-1978 practices.

Many of China’s centralising trends are not really about building up institutions. Rather, they are about seizing control of bureaucratic apparatuses for the exercise of personalised rule. Concentrating power in the hands of a single individual should not be confused with the institutionalisation of authoritarian rule.

Domestic security is one example. The new National Security Commission is directly responsible (via Meng Jianzhu) not to existing Party institutions, such as the Politburo Standing Committee, but to Xi himself. Since 2012, control of the Party disciplinary inspection apparatus has been similarly been centralised in the hands of Xi and Wang Qishan.

These institutions are also being steered in new directions. During the 1990s and early 2000s, Party disciplinary organs had been steadily professionalizing, focusing on anti-graft work rather than the rectification of political errors. Since 2012, this trend has reversed itself, with the disciplinary apparatus increasingly being used to go after not just corruption, but also sloth, failure to act, disloyalty to the top leadership and improper comments or political opinions. This represents a devolution away from institutionalised governance, not progress towards it.

China is simultaneously witnessing the breakdown of the partially institutionalised elite political practices that did develop during the reform era. The takedown of former security czar Zhou Yongkang, for example, was an obvious breach of tacit norms exempting current and former Politburo Standing Committee members from prosecution. Rumours currently swirling about age and term limit norms being potentially broken to permit Wang or Xi to stay longer in office suggest that other norms might be likely to fall as well. Veteran China watcher Wily Lam noted in a recent column that this would ‘constitute a body blow to the institutional reforms that Deng introduced in order to prevent the return of Maoist norms’.

The actual mechanisms by which the central state exerts power are also steadily sliding towards deinstitutionalised channels. Once more, these mechanisms represent a break with post-1978 practices. They include: cultivation of a budding cult of personality around Xi and a steady ideological pivot away from the Communist Party’s revolutionary socialist origins in favour of the ‘China Dream’, a revival of an ethno-nationalist ideology rooted in imperial history, tradition and Confucianism, and a revival of Maoist-era tactics of ‘rule by fear’ including televised confessions and unannounced disappearances of state officials and civil society activists alike.

Fear, tradition and personal charisma do not amount to institutional governance. As Max Weber pointed out, these are actually the antithesis of institutionalised and bureaucratic rule.

The Party-state’s reform-era efforts to build more institutionalised systems of governance are being steadily eroded. Beijing’s failure to deepen political reform when Party authorities had the opportunity to do so is now leading the system to cannibalise itself.

Carl Minzner is Professor of Law at Fordham Law School. His recent works include China After the Reform Era, Journal of Democracy (2015) and The Rise of the Chinese Security State, China Quarterly (2015). Follow him on Twitter @CarlMinzner.

Well, you have many American political leaders in the past and even today running their cities, counties and states like it was their feudal kingdoms and many of them were business people who use their political offices to maintain their business domination of the city, counties, and state plus cracking down on their political, social, and economic opponents plus trying to stifle the media and cracking down on all forms of activists.

Furthermore, you have American governors trying to steal businesses from each other or helping to take American jobs overseas because they have invested interests in those overseas operations and doing their own economic trade agreements with other nations and even profiting from it. Former California Schwarzenegger used his governor position to get the San Francisco Bay Bridge repaired using Chinese steel instead of using American steel to save costs. People found out later that the steel came from a factory that Schwarzenegger that invested in it. BTW, the Republican Party is cannibalizing itself as well.

Great points, Gunther, but what do they have to do with China being run by thuggish kleptocrats? Perhaps you can create, I don’t know… a blog and voice your carefully curated opinions there?

As for the content of this page, I’d like to say that it seems spot on. I’ve been in China for ten years and Xi has turned the Middle Kingdom on its head. Any smattering of the rule of law has been kicked to the curb, dissent is impossible and the Chinese fear a revolution.The tension is palpable. I just wonder if the PRC will ‘pull a Mussilini’ on XJP or whrther he will escape to Africa with his ill gotten cash as the next Mao creates China 2.0.

BG, my point is that the USA is being run by its own thuggish kleptocrats for the last 36 years. Look at how Dick Cheney used his position as vice president of the USA to give his former company Haliburton a lock on the Iraq contracts. Rule of law in the USA has been kicked to the curb especially when you look at the Republican president administrations. The USA has been the laughing stock of the world because of its corruption.

Gunther, BG meant that the article isn’t a comparison between China and the US or China and another country. So your feeling about how it doesn’t matter because the US is the same (in your opinion) isn’t relevant to this article. If this article had been pointing out that the US is so great and China is such a mess, then your comment would be on the merits of the article. As it is, you are defending something that no one was worrying about. The article is simply about observable changes in China and it’s governance. It isn’t an article putting down China compared to anyone else. For all you know, the author would agree with you…but you can’t know because this article isn’t about the US.