To be fair, some events, such as the Kwangju Massacre, are commemorated regularly. But the official memory is selective.

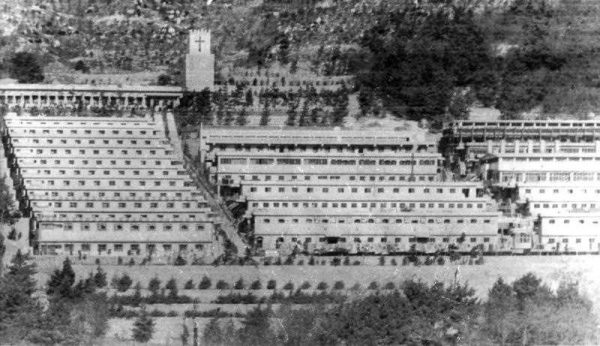

A story recently broke by the Associated Press (AP) showed a remarkable example. It revealed horrific cases of killings, rapes and abuse of thousands of people at the ‘Brothers Home’ detention centre in Busan, in south-eastern South Korea, between 1975 and 1988. This was one of 36 facilities where the government placed those deemed as ‘vagrants’ — petty thieves, political criminals, homeless, street children and the disabled — in an effort rid its cities from undesirable elements. Some were taken away as South Korea was preparing for the 1988 Seoul Olympic games.

By 1986, AP says, a total of 16,000 people were held at 36 facilities around the country. About 4000 of them were at the Brothers Home facility. There, prisoners were regularly raped, starved, beaten and killed by staff members.

At least 513 people died there between 1975 and 1986, a number that was probably much higher in reality. The facility was finally closed in 1988 after a new prosecutor stumbled upon it by accident. One of AP’s most damning revelations is that the mayor of Busan at the time, Kim Joo-ho, pleaded with the prosecutor for the facility owner’s release, while Park Hee-tae, Busan’s chief prosecutor, ‘pushed to reduce the scope of the investigation’.

Park Hee-tae later became the justice minister of South Korea and is currently an advisor to the ruling Saenuri Party. In the end, owner Park In-keun was only sentenced to two and a half years of prison time for embezzlement and charges of violating grassland management and foreign currency laws. Only a few years before his sentence, Park In-keun had received two state medals for achievements in social welfare.

The case of Brothers Home is part of a broader pattern. The South Korean government has long been ambivalent towards past crimes where government officials were either perpetrators or protected those responsible. A number of examples can be found in the atrocities before and during the Korean War, committed by South Korean government troops and militias, that the government has refused to examine in full.

In several instances during the war, in cities like Yeosu and Sunchon, large numbers of civilians were killed when the government suspected that they were hiding and aiding communist insurgents. The largest instance of such killings was the Bodo League Massacre. Before the war broke out, the South Korean government collected lists of suspected communists. Many had nothing to do with the communist movement, but local officials were given quotas for how many names they needed to collect.

When North Korea launched its invasion in June 1950, tens of thousands of people (some estimates say 100,000) were rounded up and executed, suspected of being a fifth column in waiting. A similar dynamic underpinned the Jeju Island Massacre of 1948. In its struggle to put down a leftist rebellion on the island, South Korean government troops and guerilla groups killed at least 30,000 people, approximately 10 per cent of the island’s population, many of which were civilians.

The government has established a memorial museum, but the memory of the massacre remains controversial in South Korean society. As recently as 2014, President Park Geun-hye’s nominee for prime minister, Moon Chang-keuk, claimed that the Jeju Massacre was nothing more than a communist uprising. This seems to be the official narrative for most of the massacres. As of 2014 — the last time I personally visited — the Korean War Memorial Museum in Seoul did not contain a single word about the massacres, either in English or Korean. All were described only as communist rebellions.

For decades after the war, survivors and relatives of the victims risked imprisonment if they spoke out about the killings. In 2005, the liberal Roh Moo-hyun government established a Truth and Reconciliation Commission to examine issues like the mass killings. But the commission lacked a judicial mandate, and when the conservative Lee Myung-bak government took over power in 2008, it refused to extend the mandate when it expired in 2010.

Scholars and writers I have spoken to, who either worked with the commission or followed its work closely, told me that conservatives both in government and in the media continuously undermined the commission’s work. This is presumably the same commission that an official from Seoul’s Ministry of Interior referred to when he told AP that the victims should have come forth earlier, in justifying why the current government won’t revisit the Brothers Home case.

The Park government has not been a stranger to discussing historical wounds in the case of Japanese atrocities against Korea, but domestic massacres and abuses remain too controversial and divisive to touch.

Benjamin Katzeff Silberstein is a PhD Student in Korean History at the University of Pennsylvania, and co-editor of North Korean Economy Watch.

Read Michi’s comment, American Humanism, on Chinese Comfort Women, amazon usa, if anyone is interested in Japanese and Korean comfort women. Initially, South Korean wondered why the Japanese told the big lie; they said Koreans would have risen in revolt all over the land if the Japanese had kidnapped Korean women and forced them to work in prostitution.

South Korean comfort women have filed formal complaint that they have not been apologized to by the South Korean government and not received any money for compensation. Both the South Korean government and mass media keep hushed on this.

“By this standard, however, the best colonial master of all time has been Japan…The world belongs to those with a clear conscience, something Japan has had in near-unanimous abundance (David S. Landes, The Wealth and Poverty of Nations)”.

Japan spent more money in Korea than it drew from its Korean rule. Korea recorded an anual growth of 4% on average during the thirty-five years from 1910. The population doubled and primary and middle education spread, according to Sonfa Oh, Getting Over It!: Why Korean Needs to Stop Bashing Japan. Sonfa Oh(呉善花)was a South Korean. She is a naturalized Japanese citizen.

“The Park government has not been a stranger to discussing historical wounds in the case of Japanese atrocities against Korea, but domestic massacres and abuses remain too controversial and divisive to touch.”

Or what Korea did in Vietnam?