While President Vladimir Putin had spoken of shifting focus to the East Asian market before the Ukrainian crisis, Western sanctions accelerated this proposed ‘pivot to Asia’. Sanctions led to the May 2014 signing of a record number of bilateral agreements with China. These included a natural gas deal involving the construction of a pipeline dubbed ‘the Power of Siberia’, with a view to export over 38 billion cubic metres of natural gas to China annually.

With Sino–Russian ties at their best since the end of the Cold War, the deal became a symbol of Moscow’s defiance of the West. Yet two years on, Russia has little tangible progress to show for its turn to the East.

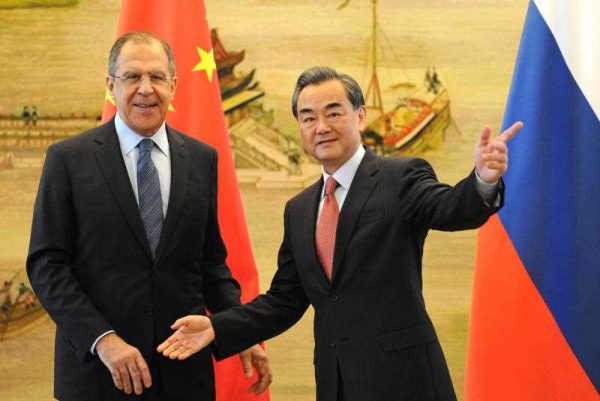

On the surface, Sino–Russian cooperation has been intensifying since sanctions hit Russia. 2015 saw Putin and Chinese President Xi Jinping strike a deal to pursue joint development projects between the Eurasian Economic Union and the ‘New Silk Road Economic Belt’. There was a major defence deal, with China becoming the first buyer of Russia’s S-400 AA defence systems and SU-35 jets. That year also saw Xi and Putin visit each other’s capitals for nationalist-inflected military parades celebrating the 70th anniversary of the end of World War II.

But these events can hardly be held up as evidence that Moscow’s ‘pivot to Asia’ has been successful. Both the 2014 gas deal and the 2015 defence deal had been in talks for years before Russia ostensibly started pivoting eastward. The ‘Power of Siberia’ launch has been tentatively postponed from 2018 to 2019, possibly even to 2021, with the gas supply only reaching the agreed-upon amount by 2024.

The economic benefits — as opposed to the political symbolism — of the gas deal for Russia have been questioned from the outset. But they are even more in doubt now in 2016 than when it was first inked, given the structural decline in global oil prices.

Despite the sheer number of bilateral agreements signed in the last two years, neither side was able to take full advantage of them due to economic malaise. In Russia, the rouble plummeted, and, despite a 30 per cent increase in China-bound oil exports, the overall exports volume of Chinese goods to Russia dropped by a parallel 30 per cent, while Russian imports to China fell by almost 20 per cent. Liquefied natural gas exports have also shrunk by over 50 per cent.

In China, the renminbi has taken a hit as well. Economic growth contracted to 6.9 per cent in 2015, its slowest in a quarter century. Trade turnover between Russia and China plunged in 2015 by almost 30 per cent. And Moscow’s efforts in creating an attractive domestic investment climate have seen mixed results. Chinese inbound foreign direct investment (FDI) to Russia fell by 20 per cent in 2015 to a mere 0.7 per cent of all Chinese FDI.

Finally, while the ‘Power of Siberia’ pipeline was envisioned as a substitute for the European market, the gas supply to China has now come to exceed demand as the economy slows down. Russia remains simply one of many gas suppliers for China, alongside its traditional partners like Australia, Qatar and more recent suppliers like Turkmenistan. These suppliers all regularly undercut Moscow. China’s view of the 2014 gas deal is perhaps best embodied in Beijing’s demand that Russia undertake all expenditures for the construction and maintenance of the new pipeline, effectively charging Moscow for the privilege of selling it gas.

Russia may yet be able to come out ahead on its ‘pivot to Asia’, though perhaps not with China, its original target partner. It is no secret that Japan has become increasingly wary, even to the point of outright hostility to China’s growing influence in the region. And while Japan has been primarily relying on and working with the United States in balancing against China, it has recently shown an opening for a closer partnership with Russia.

Tokyo’s anti-nuclear policy shift since the Fukushima incident of 2011 has created an enormous domestic demand for natural gas. Russia is well-placed to meet this demand, especially given the imbalances and uncertainties remaining in the gas deal with China. This energy could be delivered from the Russian Far East, and thus would not need to transit the South or East China seas. As a result, Japan is likely to see Russian supplies as significantly more secure than those from its current major suppliers.

A closer Russo–Japanese relationship in the energy and security spheres could prove a useful secondary balancer in northeast Asia for both Tokyo and Moscow. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s recent efforts at encouraging rapprochement ahead of the next G7 summit suggest he may agree.

Since Russia unofficially launched its ‘pivot to Asia’ two years ago, its results have largely fallen short of the Russian leadership’s expectations. While it has brought the power of its hydrocarbon sector to bear on bilateral ties, economic malaise in both countries has prevented them from reaping the fruits of this greater engagement. Beijing has shown that it is unwilling to sacrifice traditional economic and strategic relations with the West for tighter cooperation with Russia.

Promising opportunities remain for Moscow in stepping up energy and security ties with Tokyo, which has shown a consistent desire to maintain a healthy relationship with Russia. The question now is whether Russia will decide to reciprocate.

Dmitry Filippov is a PhD student at the School of East Asian Studies, University of Sheffield.

Peter Marino is an analyst of Intra-Asian politics, with a particular focus on China and Indo-Pacific Security and Economic Affairs. He holds an MSc from the London School of Economics and runs the startup Think Tank the Metropolitan Society for International Affairs. He tweets at @Globalogues.

This post contains some internal inconsistency. For example, while it is said Russia’s pivot to Asia then it goes on to mention the issues relating to China alone. A pivot to Asia should mean more than pivot to China, shouldn’t it?

Even though it argues that “economic malaise in both countries (Russia and China) has prevented them from reaping the fruits of this greater engagement” on the one hand, it states “Beijing has shown that it is unwilling to sacrifice traditional economic and strategic relations with the West for tighter cooperation with Russia” on the other.

The authors seem to suggest playing the Japan card against China. However, if “Beijing has shown that it is unwilling to sacrifice traditional economic and strategic relations with the West for tighter cooperation with Russia” as they argued, would Japan, a much closer western ally, be willing to sacrifice traditional economic and strategic relations with the West for tighter cooperation with Russia?

Russia’s ‘pivot to Asia’ also got diverted by Putin’s ‘adventures’ in Ukraine and Syria. Also, by the huge drop in the price of oil in the last year or so.

The first were by Putin’s choice. He is more invested in flexing Russia’s muscles on the international geopolitical stage than he is in helping the Russian economy and his people thrive.

The second was by world events out of his control. But he has done little, if anything, to diversify the Russian economy so it can better cope with the rollercoaster ride in the oil markets.

Seems to me that Putin is much interested in playing the geopolitical game than in dealing with admittedly complicated economic issues. Either he is out of his league or he does not have good advisors when it comes to the latter.