In this conception, Japan’s shift from Democratic Party of Japan leaderships to the Shinzo Abe Liberal Democratic Party administration, for example, was more about transitional atmospherics than foreign policy substance. If Abe dreamed of a Japan that was a great power with a more independent foreign policy stance once more, the reality cut his ambitions back to Japanese size — on breaking free of the restraint of the US security alliance framework, on his ambitions for new security laws, on changing the constitution’s peace clause and on how to play tough with China. What changes he made were adjustments on a clear trend. Japan’s foreign policy remains steady as she goes.

Some hold the same hope for the United States should Donald Trump take the US Presidency, but they may be overly optimistic.

There are other conceptions of foreign policy choice, especially when the underlying structure of national interests is undergoing great change and there are forks in the road.

What is the chance Australia’s upcoming election will make any difference to its foreign policy?

Not much, according to Russell Trood, former government Senator now back to university life, and author of this week’s lead essay.

It’s not that Trood is confident the government will be returned and therefore provide foreign policy continuity. It’s that both sides of politics in Australia reflect the structure of Australia’s interests in foreign affairs and are singing from the same foreign policy hymn book. While the outcome of the election, Trood concedes, doesn’t guarantee foreign policy continuity, it will not ‘provide much guidance on [its] future direction’. He reckons that there is a high degree of consensus among Australia’s mainstream political elites about foreign policy priorities. These include sustaining and deepening Australia’s security relationship with the United States, engaging with the Asian region including increasingly with India, countering radical extremist terrorism and protecting homeland security.

Opposition leader Bill Shorten and his colleagues have done little ‘to embellish this agenda, being content to respond to international issues as they emerge’. Shadow Foreign Minister Tanya Plibersek has stuck strictly to this script with the minor deviation of committing to redouble efforts to resolve the maritime border dispute that has ‘poisoned relations’ with Timor Leste.

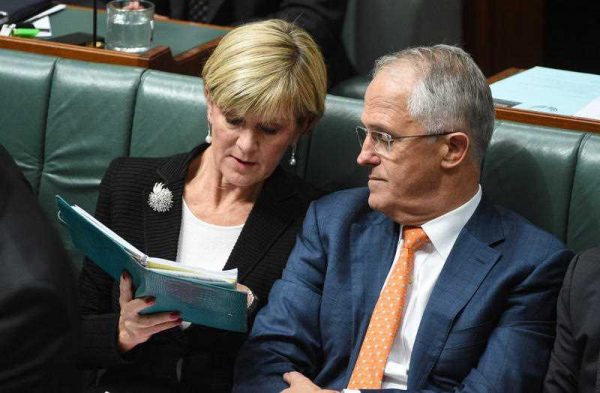

The Labor opposition appears to share the Turnbull government’s ambitions to seek deeper engagement with the global system. And the Turnbull government’s Defence White Paper, which gives priority to working with all countries to ‘build a rules based global order’, received Labor’s warm endorsement.

One interpretation of the bipartisan coincidence of views is that the Labor opposition has nothing to gain and everything to lose by challenging orthodoxy in election mode. The truth is harsher: Australia is less likely under Labor to have a creative foreign policy that represents the nuance of Australia’s national interests around its US alliance and other regional and global interests than with a re-elected Turnbull government. Turnbull has deep knowledge of foreign affairs and is less constrained by his conservative flank in this area than on domestic agendas. The thinking of Labor leader Shorten (if not all those around him, including Labor’s younger talent) is dominated by foreign policy ‘orthodoxy’ and unlikely to deliver foreign policy innovation until there is deep institutional and perhaps generational change.

Australia’s foreign policy asset is its creativity and its non-threatening capacity to be an agent of change in problem resolution.

What issues are there on Australia’s immediate foreign policy agenda?

One pressing issue, Trood says, will be to pick up the pieces with Japan after Australia failed to award the contract for the development and manufacture of its new generation of conventional submarines to the Japanese tender. This may be less of an issue than is sometimes suggested. Japan’s failure to win this tender in no way qualifies the agenda for increased security cooperation between the two countries. The affair, as it’s widely perceived in Japan, may have dented Abe’s security cred but it didn’t damage the Australia–Japan relationship. Those who suggest otherwise in Australia are closely linked to Turnbull’s predecessor, Tony Abbott, who led Abe along before accepting that there had to be a proper competitive process. Active diplomacy that saves political face there must be, but the submarine fiasco has not changed the structure of these interests one iota.

Regional concerns about the destabilising effects of China’s response to its territorial claims in the South China Sea are a top foreign policy priority. Canberra, Trood notes, is ‘wary of being drawn into confrontation with Beijing and will need to strike a finely tuned policy balance — especially with the United States — which protects its own national security interests’. Whichever side of politics wins the Australian election also has to deal with the aftermath of the Papua New Guinea Supreme Court’s decision to close its offshore refugee centre in Manus Island. The decision blows apart Canberra’s controversial and ‘elaborately conceived regime to deter asylum seekers and people smugglers from looking to Australia’ for haven. Ironically, dealing with the recent suppression of demonstrations against Prime Minister O’Neill may be a little easier as Manus Island has constrained Australia’s diplomacy towards Port Moresby. Labor is more exposed politically on refugee policy, of course, than on any other foreign policy issue and, should it regain power, will have to work hard to patch up its own differences in somehow maintaining the regime with or without PNG’s help.

While there is little sign of foreign policy initiative in all of this, Turnbull has been clearer in his statement of regional problems and a new Turnbull government seems more likely to be decisive in dealing with them than his opponents. In the medium term, a Labor government would have more room for initiative.

The region is crying out for leadership to seal the comprehensive reform that is so critical to supply-side driven growth amid continuing global economic uncertainty. Regional cooperation that goes beyond TPP (which includes less than a third of Asia) to shape a Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) would address political as well as economic objectives in the region. While the Australian government is one among sixteen that will determine whether RCEP gets up, its active and intelligent play into the process would certainly be helpful.

The EAF Editorial Group is comprised of Peter Drysdale, Shiro Armstrong, Ben Ascione, Ryan Manuel and Jillian Mowbray-Tsutsumi and is located in the Crawford School of Public Policy in the ANU College of Asia and the Pacific.