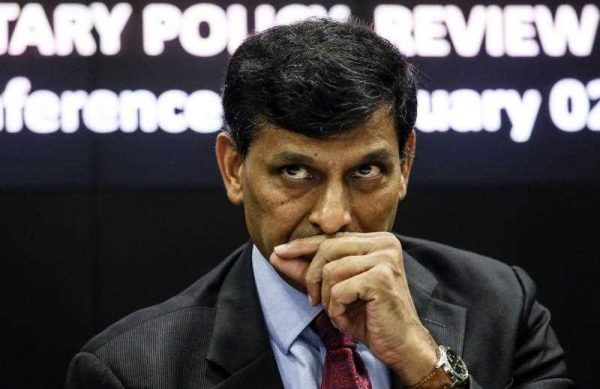

He is an outspoken champion of both economic and social reform. When push came to shove, he chose to go.

Rajan is rated by some as the world’s best central banker. His departure raises doubts about the Indian government’s commitment to structural reforms, as well as India’s position as a haven of safety amid the troubles in other emerging markets.

Famous for calling the global financial crisis before it hit, Rajan brought a clear and articulate mission to his job at the Bank. Tighter monetary policy as well as a decline in commodity prices helped tame inflation, enabling the central bank to cut interest rates by more than 1.5 percentage points since the beginning of 2015.

But for Rajan inflation was not the only target. He asked the banks, whose lending decisions have been closely tied to politics, to clean up their books. He was an outspoken critic of the government’s management of social issues, particularly crony capitalism, police corruption and religious violence. He did not define his remit narrowly, arguably necessarily, where state-owned banks and their murky links to politics still dominate the Indian economy,

But who can imagine Janet Yellen in the United States, Haruhiko Kuroda in Japan, Zhou Xiaochuan in China or certainly Glenn Stevens in Australia claiming such ground?

When Rajan took over the Reserve Bank, the economy was declining at an annualised rate of 2 per cent, consumer prices were soaring at 9.8 per cent, the rupee was down 16.6 per cent from the previous year and the current account deficit was estimated at 4 per cent of GDP. He is now leaving an economy that on current measures is growing at a rate close to 8 per cent, with inflation down to 5.8 per cent, the rupee down only 4.7 per cent from its level a year ago and the estimated current account deficit at about 1.3 per cent of GDP.

Having inherited Rajan from the Congress government, Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his Finance Minister, Arun Jaitley, gave him maximum support and space to implement the plan he’d announced after taking over in September 2013. The National Democratic Alliance government also took the flack for Rajan’s decision to not let interest rates decline more rapidly, as many demanded — including those like the combative Subramanian Swamy, close to the government’s leadership, who accused Rajan of wrecking the economy.

That Rajan succeeded in restraining inflation was partly due to plain good luck and partly to the staunch support he received from the government in maintaining tight fiscal discipline. The government also backed down twice in the face of opposition by Rajan, first to the Financial Sector Legislative Reform Commission’s recommendations and, second, to the creation of an independent public debt office in the Ministry of Finance. What more could a government do to retain this exceptional talent? Why did Modi withdraw his support over the past few months?

The economic reason may have been government worries about the weakness in bank lending. Bent on cleaning up the banks, Rajan arguably neglected the priority the government attached to boosting investment and jobs through credit expansion. But the more plausible reason is a fracture in confidence in the governor stemming from his attempt to combine the role of a senior civil servant with that of a public intellectual. And the balance, in the end, proved too uncomfortable for Modi’s political base.

Rajiv Kumar, who’s written critically of Rajan’s pushing the envelope in this context, now turns the spotlight in this week’s lead how the Modi government more generally has managed the economy in its first two years.

‘The good news’, says Kumar, ‘is that the economy has successfully weathered two years of subnormal monsoons and anaemic global economic growth. India has firmly emerged out of the group of the “fragile five” in which it found itself in the second half of 2013’ to become one of the fastest growing economies in the world. But, while the indefatigable Modi has undertaken a great number of incremental reforms, he has yet to address the main job of structural reform.

‘Major sectors like agriculture, education, health, public sector enterprise management, judicial reform and a much-needed overhaul of the administrative machinery have remained virtually untouched’. So too Kumar might have added, apart from Rajan’s brave attempt, has the central problem of reforming the banking system.

Perhaps these reforms are seen to be too politically risky and best left to the next term, Kumar suggests. Modi’s strategy seems to be to try and kickstart investment and extract the maximum possible growth from improvements to governance, while leaving the more radical reforms for later. But the undertow of resistance to letting the market do its powerful work in India remains strong.

There are also concerns about whether India’s growth numbers are being fudged, as Alok Sheel has examined in forensic detail.

The Modi government’s choice of a new Reserve Bank governor will be of more than ordinary interest to markets and strategic analysts alike. India’s growth trajectory is by no means assured. It still has to tackle the challenge of generating the minimum 10 million jobs each year required to absorb fresh entrants to the workforce, and implement radical structural reforms if it is to sustain genuine growth. And that requires much more than fiddling with statistics and playing around at the margins of reform.

The EAF Editorial Group is comprised of Peter Drysdale, Shiro Armstrong, Ben Ascione, Ryan Manuel and Jillian Mowbray-Tsutsumi and is located in the Crawford School of Public Policy in the ANU College of Asia and the Pacific.

Sounds like Rajan got fired because he did not follow the unspoken maxim for central bankers: keep your mouth shut when it comes to social and economic policy prescriptions. Perhaps Rajan might be a good candidate for PM when Modi retires and/or he fails to implement the admittedly challenging policies needed that are noted in this piece. Does he have that kind of appeal to the electorate? Or will he be a pundit/policy wonk or maybe advisor/member of some other PM’s cabinet in the years to come?

Subramaniam Swamy wasn’t content to accuse Rajan of wrecking the economy. He went further and accused him of being ‘mentally un-Indian’.

Narendra Modi himself responded to this ridiculous charge in a TV interview a day or two ago in which he said that Rajan was ‘no less patriotic than anybody else’. Presumably targeting Swamy, though without naming him, Modi said that nobody should consider himself above the system.

But unfortunately Modi didn’t avail himself of this opportunity to explain why he had thought it inadvisable to offer Rajan a second term. He merely assured viewers that Rajan would see out his current term, and claimed that he had had a very good experience working with Rajan.

It is interesting to note that, while Rajan has a Ph.D in economics from MIT, and later taught at the University of Chicago, Swamy himself has a Ph.D in economics from Harvard University, where he was supervised by no less a scholar than Simon Kuznets. Clearly one famous campus in Massachusetts breeds graduates who may later adopt anti-national thinking while another campus does not.

Some Americans might well agree, pointing to MIT’s arguably greatest intellectual ornament, Noam Chomsky, as being mentally un-American.

Ironically, Harvard is also where Amartya Sen, one of Modi’s leading critics in the Indian academic diaspora in the US, has long been a distinguished professor. One wonders how Subramaniam Swamy would explain this.