These anxieties have four main sources.

China’s international economic presence suddenly became big; people all around the world have to deal with the China factor day-by-day because the scale of Chinese economic activity means that it permeates business in even the most remote corners of the world. Whether people know very much about China or not, Chinese goods, Chinese investment, Chinese stock markets and Chinese policy strategies are suddenly visible and have impact.

What China has to deal with in keeping its economy on course to deliver moderate affluence to the Chinese people in the next decade or two is also big: no country has ever tried this in quite the same circumstance. Japan went through something similar and became an international object of public and policy attention. Its brief claim as a contender to take over as No. 1 economic power from the United States momentarily shook the established order. But China is another matter. And trying to effect a set of reforms of this scale and complexity under such intense international scrutiny in the global market is something that’s never been tried before.

The Chinese political system is also different from that of the countries which are already rich. Is China capable of delivering the goods without a political system that is closer to that of the already rich countries? How will those countries deal with China if it does succeed, given the challenge that would pose to the liberal order. And just as importantly, how will the rest of the world deal with China if it fails?

No country has walked this path before without presuming to use its economic power to carve out a slice of global political power, perhaps with the exception of Japan the second time around. Every move China makes in the political sphere, whether in the South China Sea or in setting up the AIIB, is now interpreted as a Chinese attempt to overthrow the established political order, no matter how much China protests that it has no such intention, pretends to a new era of great power relations, or insists that the Thucydides trap is irrelevant ancient history.

Collectively these are the wellsprings of global anxieties about the risk that China poses to the global economy and the global political order. Ironically, in this conception of China’s woes, whether China collapses under the weight of all these uncertain forces or succeeds in overcoming them, the China risk seems to loom larger and larger in the international consciousness.

How things have changed in a few short weeks. Not in China, of course, but in our conception of what is sure and certain in the world. China still struggles with all its challenges, its multitude of economic and social reform agendas and how to manage its economic and political interaction with the rest of the world.

But after Brexit and elevation of the European risk, and given the way in which the United States’ unusual political contest is deepening uncertainties about US recovery and American policy directions, regardless of who wins the presidency, China now appears by comparison to be a rock of economic stability in a sea of international uncertainty. Even the looming Philippine arbitration case on territorial claims in the South China Sea is now being viewed in a different light, with talk of negotiation around whatever the arbitral outcome.

China might be big, but where it is trying to take its economy is certainly not uncongenial to welfare in the rest of the world.

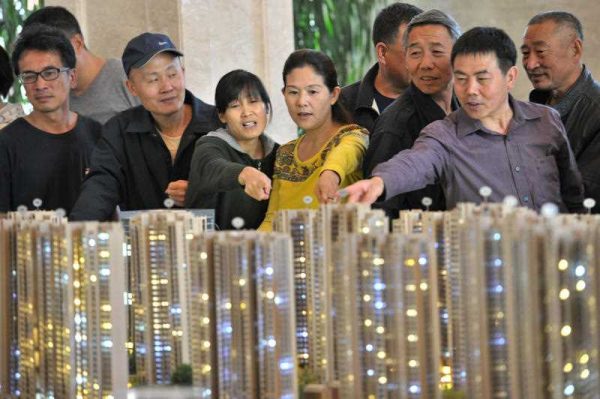

As Ross Garnaut argues in this week’s lead, China’s stated ambition of building ‘a moderately prosperous society by 2020’ will see a shift from investment to consumption, and the services share of the economy will rise from about half in 2015 to 60 per cent over the next five years.

‘And reliance on markets at home and abroad will increase as China’s engagement with the international economy deepens’, Garnaut points out. ‘This will require the development of rule of law and credibility in judicial processes. The proportionate role of state entities in the economy will be further reduced’. None of which will see a convergence between the established economic or political order any time soon, but at least it’s reliably inching along in the right direction.

‘The new economic model also emphasises deepening international integration’, says Garnaut. ‘Two-way movements of foreign direct investment will be encouraged. China will participate in international financial liberalisation through making the Chinese yuan convertible on the capital account and removing barriers to its use as an international currency. Barriers to international trade will be reduced by facilitating transactions in border areas and through multilateral trade agreements and bilateral investment agreements’. And China’s achievements in the management of the climate change externality from the impact of massive growth on its carbon footprint are impressive.

There were some rough spots along the way as China transitioned towards the new model of growth over the past year, Garnaut admits, but the main legacy from that experience, he says, seems to be acceptance for the future that ‘arbitrary interventions in markets are likely to do more harm than good’.

This might seem, indeed, to be China’s moment in the global economy, rather like the Asian financial crisis was China’s moment in Asia. Leadership of the G20 summit in Hangzhou in September presents a platform for articulation of a steady course of reform and change that could provide reassurance to a world that is now more anxious about risks elsewhere in the world.

That’s an enormous ask as China struggles to comprehend and digest the dimensions of its new global role and responsibilities. It’s hopefully a moment that has not come too soon.

The EAF Editorial Group is comprised of Peter Drysdale, Shiro Armstrong, Ben Ascione, Ryan Manuel, Amy King and Jillian Mowbray-Tsutsumi and is located in the Crawford School of Public Policy in the ANU College of Asia and the Pacific.