, averring that China’s actions have stemmed from a misunderstanding of its rights under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

Unfortunately, this likely misreads how China’s leaders view the matter. By all indications, they see at stake fundamental issues of political order, which trump the legal system within which the tribunal operates.

Upholding the historic basis of China’s rights in the South China Sea is a priority for the Chinese Communist Party because of their place in the ‘century of humiliation’ narrative, which is now a key legitimising discourse for Party rule. It is not a coincidence that the nine-dash-line map was produced by the same (pre-Communist) government that negotiated the end of China’s ‘unequal treaties’. It symbolised a reassertion of Chinese sovereignty against an international system that had been forcibly imposed on East Asia by the West. It also reflected a unilateral concept of historical Chinese authority in the region, with no attempt made to reconcile Western-derived rules of sovereign acquisition with Imperial China’s relationship to overseas territories.

A key aspect of the ‘century of humiliation’ narrative is that China historically exercised legitimate authority over far-flung lands, which was compromised by foreign aggression. This understanding of East Asian history has been so widely internalised within China that the verb commonly used by netizens to describe infringements on China’s rights in the South China Sea (瓜分) is the same one used in history textbooks to describe the nation’s 19th century ‘carving up’ by foreigners.

Surveys indicate that many Chinese citizens genuinely believe in China’s historic rights to the South China Sea and condemn the government for not enforcing them. And as Julian Ku has noted, the near unanimous support of Chinese legal scholars for the official stance seems to reflect something more than political expedience.

The Tribunal’s finding that there is no historical evidence of exclusive sovereign control by China over the South China Sea directly challenges this narrative. Faced with incongruence between the standards of modern international law and pre-Westphalian Asian political arrangements, China’s only option is to assert that the former must accommodate the latter. While these arguments are not new in Chinese non-government commentary, the arbitration seems to have pushed Chinese officialdom towards embracing them explicitly. A 3 July article published in the Party journal Qiushi by China’s vice-minister for foreign affairs castigates the judges’ lack of schooling in the ‘international legal order of ancient East Asia’.

Likewise, the Tribunal’s ruling that in any case ‘historic rights’ are extinguished where incompatible with UNCLOS has solved this issue in a legal sense, but politically it has made it harder for Beijing to trim its claims while ‘saving face’. While the treatment of ‘historic rights’ in China’s official statements responding to the award can be interpreted as doing just this, it can also be read as elevating them to the status of a legal category, in defiance of the Tribunal.

An 18 July article in the PLA Daily — which was attributed to authors at the Central Party School — supports this reading. It cites ‘historic rights’ as the basis for claiming ocean space between the South China Sea archipelagos as internal waters and for asserting traditional fishing rights throughout other countries’ exclusive economic zones, contradicting the award on both points.

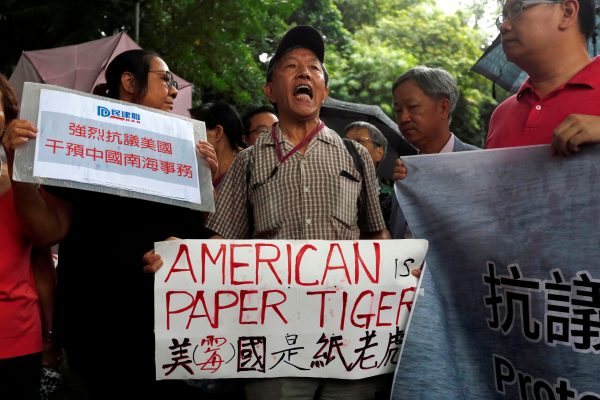

This overriding domestic political logic is amplified by a cynicism towards the process of international law and the assertion that the international system is based on observing common rules. China’s leaders likely do not view the international order as rules-based to start with. They see it as anarchical and rigged in favour of the United States and its allies, who are trying to undermine China’s ideological and territorial integrity.

From this viewpoint, it is not hard to see the arbitration as a US-devised and Japanese-enabled political weapon. Asserting China’s claims in defiance of the award is part of the wider struggle against Western ‘discourse hegemony’, just as the artificial islands are needed to undermine the perceived US-led siege line along China’s maritime frontier.

China’s response to the arbitration process should be seen in the context of the Party’s renewed commitment to both extirpating foreign modes of thought within China’s borders and contesting ideological dominance on the global stage. Asserting its interpretation of international law is just another means for Beijing to shape the international normative framework in more favourable directions. Even critics of China’s instrumental use of law in the South China Sea recognise that ‘it is a policy trajectory … that will guide the evolution of international maritime law to accommodate the rising powers of the world’.

Leaving aside considerations specific to China, the record of international tribunal decisions gives cause to doubt whether the award will be enough to modify Beijing’s behaviour. Great powers habitually don’t comply with rulings that contravene their interests where these interests are important enough to justify weathering reputational damage. To use an oft-cited example, the International Court of Justice’s Nicaragua decision may have had some positive effects, but it has not stopped great powers threatening force or using proxy warfare where sovereign claims are at stake.

Reading the award, one gets the sense that the five judges — who have dedicated their careers to the law of the sea — were determined to assert international law as an institution that has independent causal effect. But China’s responses in the fortnight since the decision suggest that this will only eventuate if other states are prepared to impose tangible costs on Beijing for non-compliance.

John Lee is a Visiting Fellow at the Mercator Institute for China Studies.

I always admire Dr. John Lee for reading the intricacy of the Chinese mind.

We should recall that all the Southeast Asian claimant states also had their ‘century of national humiliation’ through being colonised by Western countries. (Thailand was something of an exception, but is not a claimant.)

The Philippines has the distinction of having had two colonial masters, Spain and the United States (not to mention the Japanese Occupation).

Indonesia is another former ‘double colony’, having had a brief interlude of British colonial rule during the Napoleonic wars coming between much longer periods of the Dutch yoke. (Indonesia is a claimant state because of its Natuna EEZ issue, but it declines to admit it.)

Yet it is only China’s record of humiliation that features in commentary about the South China Sea, although China kept its own government or governments, and much of its territory, throughout its century of humiliation.

The key sentence in this interesting post is probably that great powers don’t abide by international rulings opposed to their interests. This is why it seems unlikely that China’s behaviour will change in any way as a result of the ruling.

.

1 It is true “that all the Southeast Asian claimant states also had their ‘century of national humiliation’ through being colonised by Western countries..”

But none of the colonial invaders like Spain, US, Britain, Holland and France disputed China’s sovereignty over the Pratas (Dongsha) , Paracel (Xisha) and Spratly islands (Nansha) Islands or the Macclesfield bank (Zhongsha) and Scarborough Shoal (Huangyan dao) (Territories).

In the 1887 Sino-Franco Convention, France agreed that all the isles, east of the Treaty delimitation line, were assigned to China. That included the Territories.

In the 1898 Treaty of Paris, signed when Spain handed the Philippines as a colony to the United States, Article III described the western limit of the Philippines as 118 degrees East longitude. China’s Territories are all located west of that longitude.

The Philippines wanted to annex the Spratlys in 1933. On 20 August that year, US Secretary of State Cordell Hull wrote that, “the islands of the Philippine group which the United States acquired from Spain by the treaty of 1898, were only those within the limits described in Article III”, and “It may be observed that no mention has been found of Spain having exercised sovereignty over, or having laid claim to, any of these (Spratly) islands”. (Kerry should read a copy of this letter).

British professor, John Carty, said “British record proves there is no dispute regarding the Spratly Islands and that China is the sole titleholder.”

On 11 Nov 1978, President Ferdinand Marcos, illegally annexed 8 features in the Spratlys, under pretext of terra Nullius, using presidential decree 1596 and renamed them the Kalayaan Island Group.

Yet China acted with restraint and wanted to settle the “disputes” by negotiation. The Arroyo administration agreed but Aquino, prodded by Uncle Sam, took the ”disputes” for arbitration in Jan 2013, after Obama’s pivot to Asia and wasted US$30 million.

2 But it is not true that “China kept its own government or governments, and much of its territory, throughout its century of humiliation.”

At the material time, a) the 2 Opium Wars (1839-1860), started by the Brits and later aided and abetted by the French, after China demanded that it stopped the trafficking of opium into the country, b) the destruction of the Old Summer Palace (Yuan Ming Yuan) in 1860 by British and French forces and theft of its treasures, (the Palace was 8 times the size of the Vatican city) and c) the Invasion of Peking during the Boxer Rebellion, 1989 to 1900 by an eight nation alliance, ( Britain, US, France, Japan, Russia, Germany, Italy and Austria-Hungary), the seat of Government was formed by the Qing dynasty (1644 to 1912) and they were Manchu invaders.

The first territory lost after the Opium wars was Hong Kong which was ceded in perpetuity to Britain but as karmic powers would have it, it was returned to China on 1 July 1997.

In 1895, after the first Japan-Sino war, Taiwan and appertaining islands were ceded to Japan in perpetuity, under one-sided Shimonosecki Treaty. Japan also annexed the Diaoyu islands in 1895 and renamed them the Senkaku islands in 1904.

Japan attacked Pearl Harbor in 1941 and ignited the Pacific War. After two atom bombs dropped into Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan declared unconditional surrender and pledged to honour the 1945 Potsdam Declaration to return all the territories stolen from China through ‘greed and violence’.

On 28 April 1952 Japan returned Taiwan as well as the Paracel and Spratly islands to the ROC, by extension to China, under the one-China policy.

But the meddling US handed the Daioyu islands to Japan for administration on May 1972, without any sovereignty, to seed a future dispute between Japan and China. Japan nationalized them in Sept 2012 while Uncle Sam turned a blind eye.

3 What China gained was not only Tibet, which the Mongol annexed and brought into China as a province during the Yuan dynasty (1271 to 1368) but also Inner Mongolia, when the dynasty collapsed. The Manchu brought Xinjiang and Manchuria into China as provinces during the Qing dynasty and when it collapsed in 1912, they became part of China.

4 China’s Golden Age, apart from the Tang dynasty, was the Ming dynasty (1368 to 1644), a period when China was the world’s only maritime superpower from 1401 to 1438, exactly 54 years before Columbus set sail to Cathay, because China invented the magnetic compass.

5 Significantly, China’s sovereignty over the Territories, which it first discovered and named during the Song dynasty (960 to 1271), was not disputed by the Tribunal or the Philippines.

Mr Tan,

In the San Francisco peace treaty, Japan renounced its claims to Taiwan, the Pescadores and the Spratlys. Could you please tell me in which Article it was that Japan gave sovereignty over these islands to the ROC? Zhou Enlai clearly didn’t see the Article you have in mind, otherwise he would not have denounced the draft treaty in August 1951 for not having allocated sovereignty.

You quote me saying that China didn’t lose ‘much of its territory’, but you go on to point out that China lost Hong Kong and Taiwan. Did that constitute ‘much of its territory’.

Mr Ward,

1.To understand why Formosa (Taiwan), the Pescadores and the Spratlys were returned to the ROC, one needs to study this Timeline:

a) After the end of the first Japan-Sino war, Formosa (Taiwan), the Pescadores were ceded to Japan in perpetuity, under the terms of the one-sided Shimonosecki Treaty, signed by Qing China and Japan on 17 April 1895.

(China’s Diaoyu islands were annexed in Jan 1895 as war booty and renamed Senkaku Islands in 1904.)

b) From 17 April 1895 to circa 2 Sept 1945 Formosa(Taiwan), the Pescadores and Senkaku were colonies of Japan.

c) Japan invaded Manchuria in 1931 and changed its name to Manchukuo. In 1937, Japan invaded China.

d) In 1938, in the fog of war, Vichy France invaded the Spratly and Paracel islands. In 1939, Japan evicted Vichy France, from these two island groups, though both were allies of Nazi Germany. When Vichy France protested Japan reasoned that it was wartime and Japan could annex China’s territories.

e) In Feb 1941, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor and ignited the Pacific War. In 1943, the Cairo Conference terms was signed by China, US and UK. In 1945, the Potsdam Declaration was signed by the US, UK and Soviet Russia.

f) When two atom bombs dropped into Japan in August 1945, Japan declared unconditional surrender. The Surrender Documents signed on 2 Sept 1945 stated that Japan “undertake for the Emperor, the Japanese Government and their successors to carry out the provisions of the Potsdam Declaration in good faith.”

g) Article 8 of the 1945 Potsdam Declaration stated unequivocally: “The terms of the Cairo Declaration shall be carried out.” And in 1943 Cairo Declaration was explicit: “Japan will also be expelled from ALL other territories which she has taken by violence and greed”.

h) On 28 April 1952, under Article 2 of the Treaty of Peace, Formosa (Taiwan), the Pescadores and the Spratly and Paracel Islands were returned to the ROC.

http://www.taiwandocuments.org/taipei01.htm

The 1951 SF Peace Treaty came into force on the same day (28 April 1952) but since Taiwan was and is 16 hours ahead of San Francisco, the Paracel and Spratly islands were already returned to the ROC first, by extension to China under the one-China policy, recognized by the US, Japan, Asean and Australia.

i) The US handed the disputed Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands to Japan for administration in May 1972, without any sovereignty. Japan nationalized them in Sept 2012.

j) China made a Declaration on 4 Sept 1958 of a 12 nm territorial water in all her territories, which included the Spratly and Paracel islands. North Vietnam’s Premier Pham Van Dong even wrote to Premier Zhou En Lai, ten days later, to acknowledge the 12 nm territorial waters as declared by China. The US, Japan, Philippines, Malaysia, and Australia did not object. Why now?

k) At the International Civil Aviation Organisation’s conference in Manila on Oct 27, 1955, a resolution was passed for the ROC to provide weather reports on the Paracel and Spratly islands.

2.You asked “Did that (HK and Taiwan) constitute ‘much of its territory’(lost)?

Lets not forget China lost the whole country to the Manchu invaders from 1644 to 1912.

Mr Tan,

The Taiwan documents link you kindly provided simply states, accurately, that Article 2 of the San Francisco peace treaty says that Japan renounced its claims to Taiwan, the Pescadores and so on. It did not say that Japan transferred sovereignty to the ROC.

You have not answered my question why Zhou Enlai denounced the treaty for not specifying who would have sovereignty over those territories. Are you contradicting China’s greatest premier?

I am very sorry that the Manchus invaded China in 1644. What about the Mongols several centuries earlier? Was that another period of national humiliation?

Mr Ward,

1 If Japan had no intention to transfer the sovereignty of Formosa (Taiwan), the Pescadores as well as the Spratly and Paracel Islands to the ROC, (Herewith call the Territories) as mandated under the Cairo Conference statement and the Potsdam Declaration which Japan pledged to honour in its surrender instrument, why bother to list these territories in Article 2 of the Treaty of Peace, Japan signed on 28 April 1952 with the ROC?

If there is any doubt that Japan had transferred to sovereignty of the Territories back to the ROC and by extension to China, the text of the Cairo Conference statement made by President Roosevelt, Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek and Prime Minister Churchill in Nov 1943 was very clear:

“The three great Allies are fighting this war to restrain and punish the aggression of Japan. They covet no gain for themselves and have no thought of territorial expansions. It is their purpose that Japan shall be stripped of all the islands in the Pacific which she has seized or occupied since the beginning of the first World War in 1914, and that all the territories Japan has stolen from the Chinese, such as Manchuria, Formosa [Taiwan], and the Pescadores, shall be restored to the Republic of China. Japan will also be expelled from ALL other territories which she has taken by violence and greed.” (Emphasis mine).

In case, you still wish to argue that the Spratly and Paracel islands were not mentioned, please read the last sentence of the Cairo Conference statement again. It’s self-explanatory.

2 Though the ROC was one of “The three great Allies fighting this war to restrain and punish the aggression of Japan” the ROC and PRC were, paradoxically, not invited to the SFPC in Sept 1951.

Was it equitable that Ceylon was a participant but not China or the ROC? No.

That showed the US and the UK could not be trusted.

To preempt any negative decision by the two colonial powers, US and the UK, on China’s territories in the South China Sea, in violation of the Potsdam Declaration and the Cairo Conference statement, Premier Zhou Enlai expressly issued a caveat on 15 August 1951 that:

“Whether or not the US-British Draft Treaty contains provisions on this subject and no matter how these provisions are worded, the inviolable sovereignty of the People’s Republic of China over Nanwei Islands (the Spratly Islands) and Sisha Islands (the Paracel Islands) will not be in any way affected.”

Did he refer to any Article in the SFPT or the Treaty of Peace. No. That caveat was prescient as it was issued 8 months before the Treaty of Peace was signed on 28 April 1952.

3 The Mongol invasion of China to start the Yuan dynasty (1271 to 1368) was indeed another humiliation for a complacent China. But the good news was China ended up with Tibet and Inner Mongolia when the Mongols fled at the start of the Ming dynasty (1368 to 1644).

England was conquered and humiliated by William the Conqueror of Normandy in 1066 but he and the Plantagenet Kings gave England the Common Law.

India was colonized and humiliated by the Brits from circa 1858 to 1947. What did India get in return from the British colonization? The Partition of India.

Indonesia was colonized and humiliated by the Dutch from circa 1799 to 1949. What did the Dutch leave behind? You are the expert on Indonesia. Maybe you can share this with the readers.

Lastly, someone suggested that to redeem China’s past humiliations, perhaps China, the future superpower, ought to adopt the same egregious ‘Rules of Engagement’ of the colonial powers in the West and start to invade and colonize weak countries in the future. Nah, it’s not in the DNA of China.

The two modern nations of the Philippines and Indonesia certainly didn’t suffer their ‘century of national humiliation’, because there was no “nation” to speak of for them until their colonial masters had amalgamated their existence. That, of course, doesn’t diminish one bit of the people’s humiliation and devastation by their colonial yoke, but certainly not technically humiliated at the “national” level.

It seems to me that China will not readily give up its claims to islands, etc in the SCS as long as it views/justifies its actions as part of efforts to overcome ‘a century of humiliation.’ If/when some incentives can be found which will get it to modify this perspective, it might lessen its claims.

Those could be positive: economic gains via more trade with the Philippines, for example. Or those incentives could be negative: armed conflict(s) which the PRC loses. The USA gave up its narrative about the domino theory and fighting communism in Vietnam after many years of a bloody and losing war. I hope this won’t become the scenario in the SCS.

China’s humiliation is not healed, not because her humiliated past is still emotionally remembered and wounding; even if she had not fallen prey to Western and Japanese imperialism, she would still be saying she had not recovered from humiliation, because equality with other peoples and nations is too alien and too humiliating for her culture and politics to accept. Standing on equal footing itself is humiliation. She would be saying humiliation until she had the whole world under heaven.

China has been both imperial and imperialistic. She has invaded and colonised three parts, Inner Mongolia, Uighur and Tibet. She has committed and is comitting atrocities in each of these parts. This has nothing to do with her humiliation.

Humiliation on her lips is the jutifying word for her imperial and imperialistic ambition.

“this (the Tribunal’s award) will only eventuate if other states are prepared to impose tangible costs on Beijing for non-compliance.” yes, I agree.

“The sort of ‘dialog’ that the Chinese empire understands is the American show of determination. China will always say whatever to save its face. However, China is listening very carefully to American behavior. China will likely yield when/where it sees American determination (Fourierr’s comment on Dialogue of the deaf: As China and America continue to talk past each other, Asia frets, June 4th, http://www.economist.com/).”

1 “She (China) has invaded and colonised three parts, Inner Mongolia, Uighur and Tibet.”

Not true. Maybe our posts crossed each other but this was what I wrote:

“What China gained was not only Tibet, which the Mongol annexed and brought into China as a province during the Yuan dynasty (1271 to 1368) but also Inner Mongolia, when the dynasty collapsed. The Manchu brought Xinjiang and Manchuria into China as provinces during the Qing dynasty and when it collapsed in 1912, they became part of China.”

Unlike Japan, there was no colonization by China. When Admiral Zheng He set sail in 1405 with 317 large ships and 22,000 armed men to Java, Malaya, Ceylon, India, Saudi Arabia and to Eastern Africa, he could have colonized any country he had wanted but the Ming Emperor’s mandate prohibited that.

Kittan,

I already made some replies about the Senkaku Isles and War and Peace of Japan in modern times, perhaps in Sam Bateman/Brinkmanship in the South China Sea helps nobody and in Mark Beeson/China’s achieving hegemony is easier said than done, EastAsiaForum.

One of the strongest impressions left in reading Chinese history is its military expansion and another is the ruthless, autocratic management of people by ruling bureaucracy. This trandition has been handed down to the present day. The golden age never existed as it does not.

“The problem is that the golden age never existed and likely to be ineffective in the modern era…The sino-centric world order was a myth backed up at different times by realities of varying degrees, sometimes approaching nil…the reality of empire was that of a hard core, or force, surrounded by a soft pulp of de, virtue…Although court records praise the Confucian wisdom of emperors, they in fact behaved like Legalists, who suggested that the well-ordered society depended on clear rules and punishment for violators rather than benevelonce…the superiority of the Chinese model in preventing war is ludicrous to anyone familiar with the details of Chinese history replete with conflict (June Teufel Dreyer, China’s Tiaxia: Do All Under Heaven Need One Arbiter?, http://www.yaleglobal.yale.edu/.)

“…the law of Legalists represented only the ruler’s fiat…Legalism left a lasting mark on Chinese civilization (Edwin O. Reischaur, East Asia: Tradition and Transformation).”

In passing, Confucius himself lived throughout his life as a Legalist. He wandered for a long time seeking an political advisory post for a king. When he found one in a country, the first advice he gave was to exterminate the opponents. Book-burning and burying the opponents alive were a Chinese patent.

A Japanese book company, Kodansh (講談社) published a twelve-volume series of Chinese history three or four years ago. It sold fifteen thousand copies in all in Japan. It was translated into Chinese and each volume sold one hudred copies in China, except the last two untranslated volumes which dealt with Mao’s era. Liang Qiachao or 梁啓超 (1873-1929) was a rare Manchurian intellectual who felt the need for China to modernize. But alas, he found that he knew hardly anything about China, because legitimacy was one very important concept in Chinese political culture and each dynasty was busy with ideologically legitimating itself by ideologically repudiating the previous one as the CCP did. Liang Quiacho was made to painfully realize that all he had for Chinese history was each dynasty’s propaganda piled up, so he came to Japan to know about China.

Both Yuan (元) and Qing (清) dynasties were not Chinese; they were Mogolian and Manchurian. They were invaders.

Chinese commentators are mostly so ethnocentric that they ignore the existence of the non-Chinese people who occupy 70% of the coastline and whose long distance sailing and trading history long pre-dates that of China. But of course these “barbarians” are non-people. The Srivijayan, Cham, Majapahit etc are figments of western imperialist imagination!

The references to various, sometimes contradictory, treaties between western colonial powers — Spain, France, UK, US — are largely irrelevant given that the occupied territories had no part in them.

If it carries on like this, China deserves the humiliation it suffered when it tried to invade Java to force it to acknowledge Chinese sovereignty!