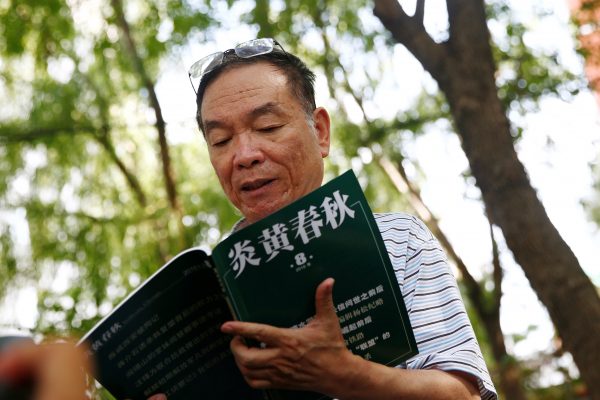

The latest campaign, coming after Xi’s tour of media outlets around the country, demands that China’s commercial press learn to put the Communist Party‘s interests before their own profits and that the ‘Party must be the media’s middle name’. The campaign even hit the respected academically-minded magazine Yanhuang Chunqiu. In mid-2016, publishers and editors who had survived innumerable media crackdowns under the previous Jiang and Hu regimes were removed.

But until recently China’s lifestyle or non-political media — similar to Hollywood’s celebrity gossip entertainment industry — had been relatively untouched. Chinese celebrity observers and journalists until this year had substantial freedom to report, speculate and comment on the day-to-day activities of China’s celebrities and public figures. But now even this door is closing. The Chinese government has introduced enforceable bans on shows that promote ‘Western lifestyles’ or report on the ‘private affairs, relationships or family disputes’ of ‘stars, billionaires or internet celebrities’.

The most immediately noticeable impact was to reduce cleavage shots in the hit drama The Empress of China, known online as ‘The Saga of Wu’s Breasts’. But the censor’s knife soon hit other popular programs as well. Shows featuring time travel, which have technically been banned for several years now, have been attacked once again.

Similarly, other shows like the wildly popular Where Are We Going, Dad? — which gives viewers a peek into the lives of China’s ultra-elite children — have been singled out for deletion, as have other similar formats. Even before Xi’s tenure there were similar attacks against individual shows or genres. But this is the first campaign since the early 1990s to go after non-political shows on such a scale.

So why has the Xi administration decided to curtail such seemingly innocuous programming? Xi’s rapacious desire to bring the media to heel and control all levers of power is certainly part of the answer. But Xi himself provided a more compelling rationale in a speech in Beijing on 21 October 2016. Relying on a traditional Chinese view of power, Xi has argued that power is fundamentally based not on guns and coercion but on belief and acceptance. ‘Without the support of an unbreakable belief and lofty ideal and faith’ Xi argued, success is ‘unimaginable’.

In this view, shows that promote ‘Western lifestyles’ or ‘immorality’ do more than just titillate the audience — they actually represent a Trojan horse that will undermine Xi and the Party’s power from within. As the deputy director of the main state media regulator has written, only shows with genuinely Chinese content can depict the socialist core values and Chinese fine traditions the state requires.

Sinologist Kerry Brown has recently written that one of the most important forms of power in contemporary China is ‘control of the grand narratives and stories of Chinese society’. Xi’s administration clearly feels that Western-inflected lifestyle television has the potential to challenge these narratives simply by existing.

During most of the reform era, the Chinese Communist Party has emphasised its nationalist and economic credentials in an unwritten bargain with the population. As long as growth has remained robust, the Party’s hold on citizens’ loyalty has been firm. But as growth falters, Party leaders have been casting about for additional sources of legitimacy and to bolster the Party’s image in the popular imagination.

The Party’s official revival of Confucianism serves part of this role and the leadership has reemphasised in recent years the battle for China’s ‘hearts and minds’. To supplement this campaign, Xi Jinping has advanced the idea of the ‘China Dream’ as a new potential unifying ideology. But Xi also believes the lustre of this impossibly vague slogan is challenged by media programs that by their very existence directly or indirectly show off the West’s relative economic and cultural success. Foreign cultural threats are an anathema to the man who wants to be ‘Chairman of Everything’.

And so the crackdown on seemingly innocuous programming continues. Ironically, as media scholar Wanning Sun points out, China already does have a few successful indigenous lifestyle television shows that can compete directly with Western products. But because they are driven by commercial rather than political considerations, ‘Chinese authorities may be reluctant’ to allow and promote them.

The market seems to be more successful than state directives in making compelling programming that actually builds up and maintains this kind of symbolic state power. But the market’s continuing success requires a hands-off approach from Xi and other central authorities. A man who would control everything is unlikely to embrace this soft-touch approach, so Xi’s assault on lifestyle television is likely to continue for the foreseeable future.

Jonathan Hassid is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at Iowa State University.

‘unshackle the media in his quest to root out China’s institutional corruption.’ Yeah, that works really well for us, so why not for China?

‘Sinologist Kerry Brown has recently written that one of the most important forms of power in contemporary China is ‘control of the grand narratives and stories of Chinese society’.

Kerry should spend some of his spare time explaining that one of the most important forms of power in contemporary Australia is Rupert Murdoch’s ‘control of the grand narratives and stories of Australian society’. If I had to choose who’d control my country’s narrative I’d pick Xi in a heartbeat.

Xi Jinping has advanced the idea of the ‘China Dream’ as a new potential unifying ideology. Rubbish. The ‘China Dream’ was first advanced 2500 years ago by Confucius. It’s part of the Taiwanese national anthem and has been advanced by every Chinese leader since the Revolution. The dream that Xi refers to is a Xiaokang Society, usually translated as Lesser Prosperity. China will achieve it for the first time in 2020 and it will be officially acknowledged on June 3, 2021.

If you want to write about China, learn something about China first.

The ongoing crackdown on Hong Kong ‘dissidents’ also suggests that Xi is not going to tolerate anything or anyone who dares to dispute his rule. I heard/read somewhere that there is talk of extending his 10 year term as the country’s leader. That would herald a significant return to the past in some ways.