as the first and only head of state of Central Asia’s largest nation.

Spanning the western border of China and the eastern borders of Russia, Kazakhstan’s economic and security relationships play a strong role in defining the contours of Eurasia’s regional architecture. Kazakhstan’s stability and political autonomy in the post-Nazarbayev era will be key to the preservation of the fragile power equilibrium in the Eurasian landmass between the West, Russia and China.

If Astana were to deviate from Nazarbayev’s foreign policy orientation — particularly in the event that a power struggle to succeed the president left the triumphant contender beholden to either Moscow or Beijing — then the current relative balance among the global powers would be disrupted, with either Russia or China enjoying an inordinate advantage in the Eurasian strategic architecture.

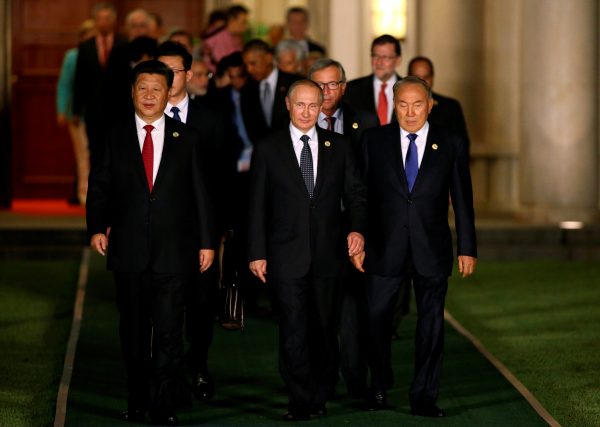

Nazarbayev’s ‘multi-vectored’ foreign policy for Kazakhstan — its careful three-way balancing among Russia, China, and the EU and the United States — has helped maintain a sort of great power equilibrium in Central Asia. To preserve its autonomy and prosperity in the face of new political and economic challenges that began in 2014, Kazakhstan increased its efforts to ‘rebalance Westwards’, offsetting the threat of Russian hard power and of Chinese soft power by deepening its security cooperation with the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) and economic cooperation with the EU.

But Russia’s irredentist activities in Ukraine combined with the general revanchist rhetoric emanating from Moscow has continued to alarm Kazakhstan.

Five months after the annexation of Crimea, Russian President Vladimir Putin questioned the legitimacy of Kazakhstani statehood at Russia’s annual national youth forum in late August 2014. In his speech, which coincided with Kazakhstan’s celebration of its Constitution Day holiday, the Russian president claimed that Kazakhs had no state before the leadership of Nazarbayev. Putin also implied that after Nazarbayev’s passing ‘Kazakhs’ — not Kazakhstan — would be part of the ‘greater Russian world’.

That same year, the precipitous drop in oil prices along with Western sanctions on Russia brought Kazakhstan’s hydrocarbon-based economy to a virtual standstill, forcing the country to devalue its currency by 19 per cent in February.

China’s ambition to fill the economic gap in Kazakhstan and other Central Asian republics has also triggered concern in Kazakhstan and throughout the region. China has already collectively invested well over US$250 billion in Kazakhstan and the other Central Asian republics through its Silk Road Economic Belt initiative. In November 2014, Beijing established a US$40 billion Silk Road infrastructure fund to further finance Chinese investments in Central Asia. While China was once welcomed as an important countervailing economic force to Russia, widespread concern within the Central Asian republics over Chinese economic hegemony has become palpable.

Now in 2017, with a resurgent Russia on one side and the economic juggernaut of China’s Belt and Road Initiative on the other, Nazarbayev is looking to preserve Kazakhstan’s autonomy beyond his own tenure.

Some Kazakh politicians have interpreted the president’s reform initiative as simply a way to shore up his legacy as nation-builder by placing the responsibility for Kazakhstan’s worsening economic situation on its parliament. But the devolution of the presidency’s authoritarian powers onto the country’s legislature should be viewed as Nazarbayev’s attempt to ensure a smooth transition and the continued progress of the now 25 year old Kazakhstan nation-building project that seeks to diversify its economy and develop its human capital. In a nationwide address, Nazarbayev remarked that Kazakhstan’s presidential system was necessary because it provided stability after the fall of the Soviet Union, but the system has outlived its usefulness.

In his own way, Nursultan Nazarbayev may become a Central Asian version of Lucius Quintius Cincinnatus, the 5th century BC leader of the Roman Republic who voluntarily relinquished his near-absolute authority and who served as an exemplar for the first US president George Washington as well as several other founders of modern Western democracy. If Kazakhstan’s political transition succeeds, not only will Nazarbayev rightly be deemed the ‘father of his country’ but he will have made a critical contribution to preserving strategic equilibrium on the Eurasian continent.

Micha’el Tanchum is a Fellow at the Truman Research Institute for the Advancement of Peace, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem and the Energy Policy Research Center at Bilkent University, Ankara, Turkey. You can follow him on Twitter at @michaeltanchum.