On Park’s departure the focus shifted sharply to the upcoming presidential election. In the aftermath of Park’s impeachment, for the first time in any South Korean presidential election there is no strong conservative candidate.

South Korean politics has been dominated by a powerful conservatism since liberation from the Japanese in 1945, during the Korean War (1950–1953), the Cold War, and following democratisation in the late 1980s. The foundations of Korean conservatism, though difficult to pinpoint, are variously shaped by strong anti-communist and anti-North Korea sentiment, support for South Korea’s relationship with the United States, and a pro-business, anti-labour ideology.

Throughout South Korea’s modern political history presidential elections have been fought between a strong ruling conservative candidate and a progressive opposition candidate. Of the 18 previous presidential elections, South Koreans voted the opposition in only twice and with small margins — with the election of Kim Dae-jung in 1997 and Roh Moo-hyun in 2002. South Korea’s conservatives have had near hegemonic power, by large electoral margins in most other elections.

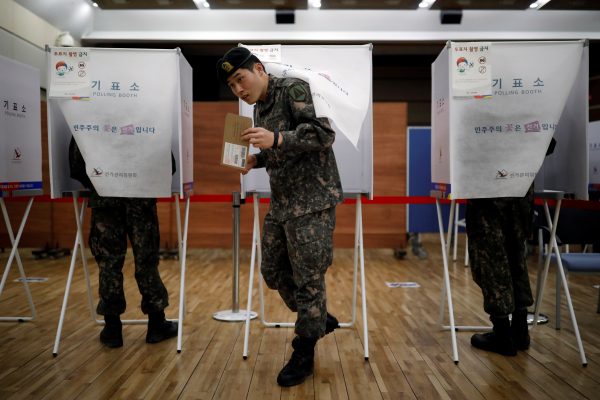

The election this week is likely to deliver a big shock for conservative Koreans. The Democratic Party of Korea’s Moon Jae-in is on top in the polls and Ahn Cheol-soo of the People’s Party’s — neck and neck in distant second place — are both candidates with progressive backgrounds.

Ahn was a political novice in the previous election in 2012 yet he was popular enough to compete with Park Geun-hye and Moon Jae-in. Back then, he resigned as a candidate to increase the chances of Moon’s victory. The conservative candidates Yoo Seung-min and Hong Jun-pyo, representing the two parties that split from the former ruling Saenuri party, do not have enough support to seriously challenge the progressive frontrunner.

In a break from historical precedent, conservative voters are drifting away from South Korea’s usual conservative parties.

In the lead-up to the election, the real competition has been between Moon and Ahn. In a poll conducted on 14 April, 40 per cent of respondents were for Moon, 37 per cent for Ahn, and less than 10 per cent for other candidates. In the past week, the polls have given Hong a lift and, with the defection of some of Yoo’s followers, he’s edged up towards Ahn.

One puzzle in the campaign is that Ahn, who has always been a progressive or at least moderate politician with no history of conservatism, seems to have draped himself in a conservative mantle. Conservative voters, absent a strong candidate from the right, began to strategically hedge against a more progressive president in Moon. Ahn, who represents a mini-party with only 40 representatives out of 300 in the National Assembly, gradually shifted his political stance rightward.

If there are no dramatic changes in the next few days, South Korea seems set to elect a relatively progressive president on Tuesday. Whoever the new president he will face strong political demands for fundamental reforms, catalysed by the massive candlelight demonstrations that began in 2016.

Constitutional revision to reduce the power of the ‘imperial president’ is one of the key issues on the political agenda. Addressing socio-economic polarisation and growing inequality also requires breaking through resistance from vested interests such as chaebol conglomerates and South Korea’s bureaucracy. Solving diplomatic conundrums like the deployment of the Terminal High Altitude Area Defence system, North Korea’s nuclear tests and the ‘comfort women’ issue will require dexterity and skills of persuasion that all take time for a new leader to master.

The new president will be frustrated by the distribution of seats in the National Assembly which are currently stacked against reform. No single party has majority status. A good deal of political manoeuvring and coordination will be needed to hammer out reform agendas and weld deals among politicians, political parties and community stakeholders.

South Korea’s first decisively-elected progressivist could yet turn out to be a ‘lame duck’ president. What matters most to South Korea’s politics and democracy is not so much who becomes the new president but how strong are his will for reform and his capacity to persuade the country of its priority.

Kim Kee-seok is Professor of Comparative Politics at the Department of Political Science, Kangwon National University.