After accepting a congratulatory phone call from Taiwan’s President Tsai Ing-wen, Trump went on to question why the United States needed to support a ‘one China’ position and avoid improving contacts with Taiwan.

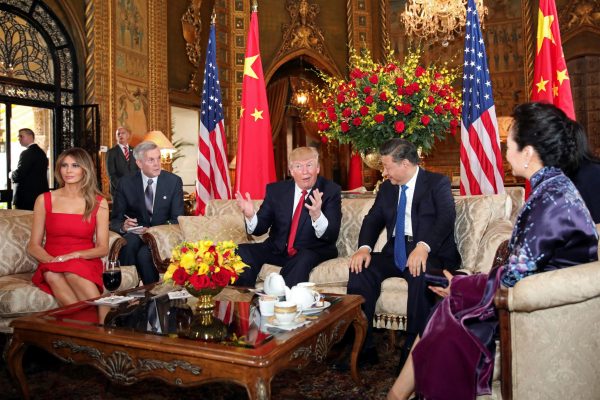

President Trump eventually was persuaded to endorse — at least in general terms — the traditional US view of the ‘one China’ policy. Though his informal summit meeting with President Xi Jinping in early April went well, Trump has put his Chinese counterpart on the defensive. He made clear how quickly he could take a wide range of surprise actions with serious negative consequences for China. Beijing was compelled to prepare for contingencies from a US president who values unpredictability and tension in achieving goals.

After the summit, the Trump government kept strong political pressure on China to use its economic leverage to halt North Korea’s nuclear weapons development. While stoking widespread fears of conflict on the peninsula, President Trump stressed his personal respect for President Xi. He promised Beijing easier treatment in pending negotiations on the two countries’ massive trade imbalance and other economic issues.

China’s new uncertainty over the US president added to reasons for Beijing to avoid — at least for now — controversial expansions in the disputed South China Sea. How long this will last is a guessing game.

Further, the Trump administration’s preoccupation with North Korea and China reinforced a prevailing drift in US policy in Southeast Asia. Trump and his officials have announced the end of the Obama government’s ‘pivot to Asia’ policy and repudiated its economic centrepiece — the Trans-Pacific Partnership.

What exists of Trump’s Southeast Asia policy at best reflects belated and episodic attention based on a poorly staffed administration with no coherent strategic view. Only very recently have they begun to take steps to show interest in positive engagement with Southeast Asia.

On the South China Sea disputes, the Trump government has followed a cautious approach. It avoided for some time the periodic freedom of navigation exercises by US Navy ships targeted against Chinese claimed land features deemed illegal by an international tribunal in 2016. In Indonesia, Vice President Pence repeated the administration’s insistence on ‘fair trade’ with Indonesia, one of many Asian countries whose trade surplus with the United States has placed them under review by the new administration.

Human rights issues in Southeast Asia — ranging from authoritarian strongman rule in Cambodia and Communist dominance in Vietnam to the newly democratic Myanmar government’s controversial crackdown on the oppressed Rohingya community — have received much less attention from the Trump government than from previous administrations. Recent presidential invitations to Philippine and Thai leaders underline this new US pragmatism on human rights issues.

Southeast Asian officials are correct in complaining that they have few counterparts in the Trump government, particularly in the State and Defense departments, due to the administration’s remarkable slowness in nominating appointees. As they wait, those seeking a coherent and well-integrated US strategy toward Southeast Asia are likely to be disappointed. Barring an unanticipated crisis, the preoccupations of the Trump administration with other priorities seem likely to continue for the foreseeable future.

On key issues in Southeast Asia, there appears to be broad agreement within the Trump government — shared by congressional leaders — on the need to strengthen the US security position in Southeast Asia along with the rest of the Asia Pacific. President Trump’s proposed increase in defence spending will presumably support recent congressional legislation such as the Asia Pacific Stability Initiative and the Asian Reassurance Initiative Act.

But achieving a unified and sustained position on US economic and trade issues — with Southeast Asia or elsewhere — promises to be more difficult than consistency on security and foreign policy values. Key appointees have records very much at odds with one another. Some strongly identify with the president’s campaign rhetoric pledging to deal harshly with states that ‘treat the United States unfairly’ and ‘take jobs’ from US workers. Others stick to conservative Republican orthodoxy in supporting free trade. Policy is said to move back and forth between these two camps, and where Trump himself will come down in this debate is very unclear.

How much influence the United States will lose or gain in these uncertain surroundings remains to be seen. Much will depend on how well or how poorly China ‘fills the gap’ caused by drifting US policy. For now, it seems that US–China competition in Southeast Asia is more likely than not to remain a muddle for some time to come.

Robert Sutter is Professor of Practice of International Affairs at the Elliott School of International Affairs, George Washington University.

An extended version of this article appeared in the most recent edition of East Asia Forum Quarterly, ‘Strategic diplomacy in Asia’.

“One China” is NOT the prevailing view of most Americans: they see Taiwan as a separate, self-governing country since the end of the 20th C. Chinese Revolution. Most agree that Tibet is also it’s OWN country. China grabbing other nations by citing things “as they were centuries ago” is not good policy or mind-set. Freedom is a growing movement around the world, and China should learn from that action.