Unfortunately, the bellicose rhetoric which has long been Pyongyang’s stock in trade was matched by some of the language emanating from Washington. Rather than weigh his every word carefully and diplomatically, Donald Trump appears to say (and tweet) whatever comes into his head. For the United States to match the DPRK’s menaces with threats of its own is no way to solve the North Korean question. Indeed, it potentially puts at risk the very security that US deterrence has helped to maintain on the Peninsula since the 1953 Armistice.

South Korean President Moon Jae-in’s public assurance that Washington would do nothing without consulting Seoul served only to highlight fears that under Trump, the potential risk of rash unilateralism was only too real. Some of Trump’s comments also seemed to imply that this was a duel of two, rather than a complex conflict in which other states — not least of which are South Korea and Japan — also have a vital stake.

The highlight of this competitive braggadocio came in August. Trump warned on 8 August that ‘North Korea best not make any more threats to the United States’ else it would face ‘fire and fury’. Days later, Pyongyang warned that Kim Jong-un was studying a plan to launch four intermediate-range ballistic missiles that would rain ‘enveloping fire’ on waters off Guam.

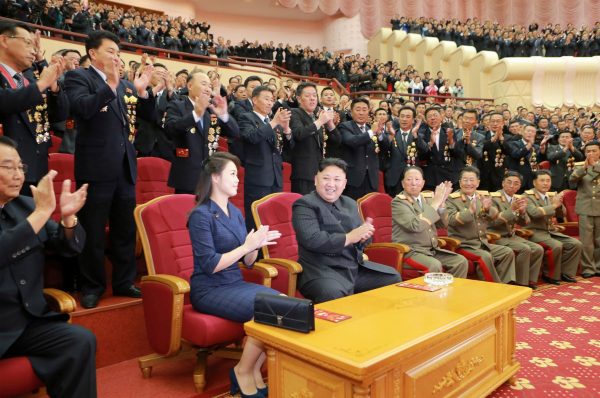

Then on 15 August (Liberation Day, a holiday in both Koreas), Kim Jong-un resurfaced after a fortnight’s absence, and magnanimously announced a postponement: he would observe the ‘foolish and stupid conduct of the Yankees’ a bit longer before deciding whether to give the order to fire. The world breathed again, with the ineffable Trump even tweeting congratulations to Kim for his ‘very wise and well-reasoned decision’.

Yet this was a classic DPRK ploy: ratchet up tensions, then claim spurious credit for drawing back from the brink. If Trump really believes the United States gained ground in this exchange, he deludes himself. Worse, if he attributes his imaginary success to talking tough, the world may be in for more of the same.

On 6 August the UN Security Council passed yet another unanimous resolution censuring the DPRK for its ICBM tests. It further tightened economic sanctions, and it was claimed that this could cut Pyongyang’s revenues by as much as US$1 billion. But as ever, this hinges on how far China enforces these new measures.

North Korea has been under UN and other sanctions for over a decade now, ever since its first nuclear test in 2006. The paradox and puzzle for economists is that not only have these failed (unlike with Iran) to force the regime into negotiations (much less economic collapse) but their impact is barely visible. If anything, especially in the Kim Jong-un era, the country — or at least Pyongyang — looks to have enjoyed a modest boom, with new construction proceeding apace.

Among those who strive to estimate North Korea’s growth is the Bank of Korea, South Korea’s central bank. Their past figures have erred towards low estimates of growth, but even its latest estimates seem to confirm this surprising resilience. On its reckoning, North Korea’s GDP grew by 3.9 per cent last year — its best performance this century and faster than the South itself managed in 2016. It remains to be seen whether the latest tranche of UNSC and other sanctions are any more effective in hobbling Kim’s nuclear programs than their predecessors have been.

The storm continues elsewhere. Ulchi-Freedom Guardian, one of two regular annual joint US–ROK military exercises, was held as usual in August, and as always, North Korea denounced these war games as a prelude to invasion.

Last year, rising tensions on the Peninsula were reflected in the enlarged scale of these exercises, but this time, the reverse occurred — the number of US forces participating dropped from 25,000 in 2016 to 17,500 in 2017. Similarly, plans to bring in significant additional US strategic assets for the exercises seem to have been dropped. Behind the fiery rhetoric, that gesture will not have gone unnoticed in Pyongyang.

Might we be heading towards the calmer waters of diplomacy? Kim Jong-un seems uninterested, and no other power seems yet ready to formally acknowledge a grim truth: the ‘nuclear genie’ is out of the bottle, and the DPRK has succeeded in its quest to become a viable de facto nuclear state. The best hope now is a monitored freeze — full denuclearisation is no longer on the cards.

As Trump’s until-recently director of strategy Steve Bannon noted: ‘Until somebody solves the part of the equation that shows me that ten million people in Seoul don’t die in the first 30 minutes from conventional weapons, I don’t know what you’re talking about, there’s no military solution here, they got us’.

The Economist had earlier gamed such a possible war scenario in chilling detail as part of the cover story in its August 5 issue. This showed Trump and Kim enveloped in a mushroom cloud under the headline ‘it could happen’.

Yes, it could. But at such an appalling and self-defeating cost, with any luck it will not.

Aidan Foster-Carter is Honorary Senior Research Fellow in sociology and modern Korea at Leeds University and a freelance consultant, writer and broadcaster on Korean affairs.

An extended version of this article first appeared here at NewNations.