That month the LDP also lost heavily in the Tokyo Metropolitan Assembly election, in which a newly formed party — the Tomin First No Kai (Tokyoites First), led by Tokyo Governor Yuriko Koike — captured the largest share.

So why call the snap election?

The political landscape shifted in August and September in favour of the LDP leading Abe to gamble that invoking his constitutional right to dissolve the lower house at this time would pay off.

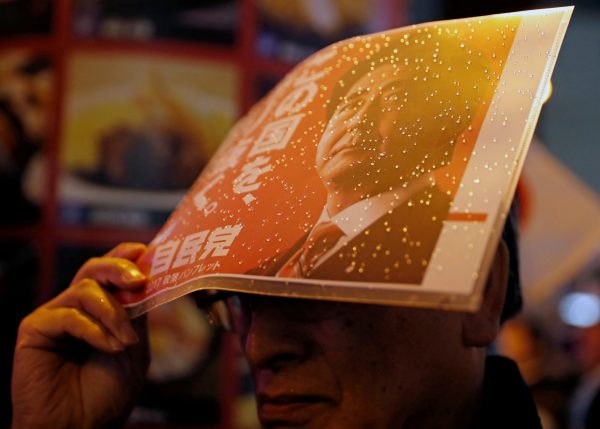

Among the factors contributing to the call of the snap election was an increase in the coalition’s approval rating following a cabinet reshuffle on 3 August. The new cabinet, which Abe labelled a ‘results-oriented cabinet of doers’, includes some popular and outspoken leadership contenders, such as Taro Kono and Seiko Noda.

The ministers who had earlier tarnished the cabinet’s image are gone. Former justice minister Katsutoshi Kaneda was sacked over his poor explanations about the controversial anti-conspiracy bill. The other martyr was former defence minister Tomomi Inada for her alleged involvement in the cover up of documents detailing the dangers the Self-Defense Forces faced in South Sudan.

The opposition is in disarray. Even though the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) tried to revamp its image with a new brand — the Democratic Party (DP) — the change did nothing to recover from the party’s meagre support rate, which hovered around 3–4 per cent. Its leader, Renho, stepped down abruptly in July due to the party’s poor performance in the Tokyo Metropolitan Assembly elections and her mishandling of a scandal concerning her citizenship. Most Japanese citizens had no interest in the subsequent DP leadership election, which was won by Seiji Maehara of the party’s conservative faction over the liberal Yukio Edano.

Koike threatened to dramatically raise the stakes in Abe’s gamble, just as the election was called, with the launch of her new national level Party of Hope. The new party attracted significant media attention as 14 Diet members, including DP converts and even an incumbent vice minister from the LDP, defected to join Hope.

In a still more dramatic move a few days later, DP leader Maehara formed an agreement with Koike that all DP members would run under the Hope banner, meaning that the DP would eventually disband. As the new leader of the soon-to-disappear DP explained, he ‘would do anything‘ to topple the Abe administration, including bandwagoning on the coattails of the media-savvy populist governor.

But the mania surrounding Hope soon dissipated.

Even though Maehara requested that Koike resign as governor and run in the election to attract more votes, Koike refused. This left Hope without a prime ministerial candidate, confusing voters who want a clear alternative to Abe.

The united opposition front against the LDP also did not materialise as Maehara had planned. Koike did not want a simple merger. Rather, she screened out those ex-DP members with different views on national security.

Discontented with this exclusive nomination policy, left-leaning ex-DP members, including Edano and former prime minister Naoto Kan, launched the Constitutional Democratic Party of Japan (CDPJ) on 2 October. The existing leftist parties, the Japan Communist Party (JCP) and the Social Democratic Party (SDP), will selectively support these left-leaning candidates by withdrawing candidates from some districts.

The rise of Koike and her party has thus had two ramifications.

The first is the emergence of a centre-right opposition party that is little different from the LDP. Having learned from the downfall of the DPJ, which was largely caused by party disunity, Koike sought to admit only ideologically cohesive and loyal members into her party. But its opponents have branded it as nothing but a spinoff of the LDP.

Second, opposition fragmentation — the very reason the LDP–Komeito coalition won so easily in 2012 and 2014 — is still in play. The exclusive nomination style of Koike proved to be very costly, as evidenced by the birth of yet another new liberal party and dozens of independent candidates refusing to work with her. In as many as 208 of the 289 single-member districts, voters were split between three choices — the LDP–Komeito coalition, the conservative-right opposition (Hope and the Osaka-based regional party Ishin No Kai) and the liberal–left opposition (CDPJ, JCP and SDP) — which served to divide the anti-LDP vote.

Yet again the Abe government has won another easy victory as Japan opposition parties continue to flounder.

Kuniaki Nemoto is Associate Professor of Political Science at Musashi University.